Umpolung

The vast majority of important organic molecules contain heteroatoms, which polarize carbon skeletons by virtue of their electronegativity.

Therefore, in standard organic reactions, the majority of new bonds are formed between atoms of opposite polarity.

Biochemical and industrial processes can provide inexpensive sources of chemicals that have normally inaccessible substitution patterns.

The net result of the benzoin reaction is that a bond has been formed between two carbons that are normally electrophiles.

In this example, the β-carbon of the α,β-unsaturated ester 1 formally acts as a nucleophile,[4] whereas normally it would be expected to be a Michael acceptor.

For comparison: in the Baylis-Hillman reaction the same electrophilic β-carbon atom is attacked by a reagent but resulting in the activation of the α-position of the enone as the nucleophile.

Biological processes can employ cyanide-like umpolung reactivity without having to rely on the toxic cyanide ion.

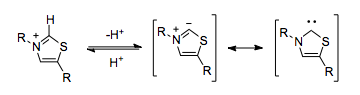

The thiazolium ring in TPP is deprotonated within the hydrophobic core of the enzyme,[5] resulting in a carbene which is capable of umpolung.

In the absence of TPP, the decarboxylation of pyruvate would result in the placement of a negative charge on the carbonyl carbon, which would run counter to the normal polarization of the carbon-oxygen double bond.

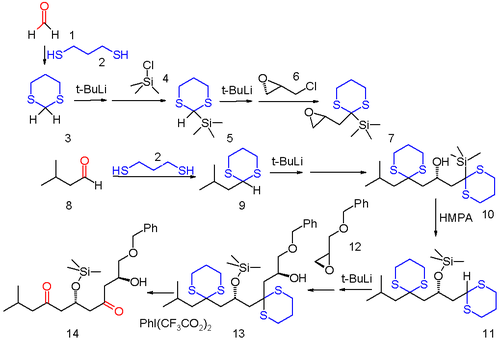

When the dithiane is derived from an aldehyde such as acetaldehyde the acyl proton can be abstracted by n-butyllithium in THF at low temperatures.

Sulfide 3 is first silylated by reaction with tert-butyllithium and then trimethylsilyl chloride 4 and then the second acyl proton is removed and reacted with optically active (−)-epichlorohydrin 6 replacing chlorine.

The anion relay chemistry tactic has been applied elegantly in the total synthesis of complex molecules of significant biological activity, such as spongistatin 2[8] and mandelalide A.