Underwater explosion

[3] Underwater nuclear tests close to the surface can disperse radioactive water and steam over a large area, with severe effects on marine life, nearby infrastructures and humans.

The Baker nuclear test at Bikini Atoll in July 1946 was a shallow underwater explosion, part of Operation Crossroads.

The base surge rose from the surface and merged with other products of the explosion, to form clouds which produced moderate to heavy rainfall for nearly one hour.

Gas from the bubble broke through the spray dome to form jets which shot out in all directions and reached heights of up to 1,700 ft (520 m).

[6] The heights of surface waves generated by deep underwater explosions are greater because more energy is delivered to the water.

During the Cold War, underwater explosions were thought to operate under the same principles as tsunamis, potentially increasing dramatically in height as they move over shallow water, and flooding the land beyond the shoreline.

Méhauté et al. conclude in their 1996 overview Water Waves Generated by Underwater Explosion that the surface waves from even a very large offshore undersea explosion would expend most of their energy on the continental shelf, resulting in coastal flooding no worse than that from a bad storm.

[2] The Operation Wigwam test in 1955 occurred at a depth of 2,000 ft (610 m), the deepest detonation of any nuclear device.

The drastic 60% loss of energy between oscillation cycles is caused in part by the extreme force of a nuclear explosion pushing the bubble wall outward supersonically (faster than the speed of sound in saltwater).

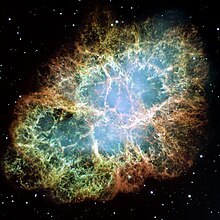

The bubble becomes less of a sphere and looks more like the Crab Nebula—the deviation of which from a smooth surface is also due to Rayleigh–Taylor instability as ejected stellar material pushes through the interstellar medium.

About six seconds after detonation, all that remains of a large, deep nuclear explosion is a column of hot water rising and cooling in the near-freezing ocean.

This is incorrect; the bombs were placed in shafts drilled into the underlying coral and volcanic rock, and they did not intentionally leak fallout.

Hydroacoustics was originally developed in the early 20th century as a means of detecting objects like icebergs and shoals to prevent accidents at sea.

When the CTBT was adopted, 8 more hydroacoustic stations were constructed to create a comprehensive network capable of identifying underwater nuclear detonations anywhere in the world.

[12] Each hydrophone records 250 samples per second, while the tethering cable supplies power and carries information to the shore.

T-phase monitoring stations record seismic signals generate from sound waves that have coupled with the ocean floor or shoreline.

[15] T-phase stations are generally located on steep-sloped islands in order to gather the cleanest possible seismic readings.

If a potential detonation has been identified by one or more stations, the gathered signals will contain a high bandwidth with the frequency spectrum indicating an underwater cavity at the source.