Uneconomic growth

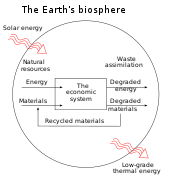

"[4] The cost, or decline in well-being, associated with extended economic growth is argued to arise as a result of "the social and environmental sacrifices made necessary by that growing encroachment on the eco-system.

Canadian scientist David Suzuki argued in the 1990s that ecologies can only sustain typically about 1.5–3% new growth per year, and thus any requirement for greater returns from agriculture or forestry will necessarily cannibalize the natural capital of soil or forest.

[7][8] For example, given that expenditure on necessities and taxes remain the same, (i) the availability of energy-saving lightbulbs may mean lower electricity usage and fees for a household but this frees up more discretionary, disposable income for additional consumption elsewhere (an example of the "rebound effect")[9][10] and (ii) technology (or globalisation) that leads to the availability of cheaper goods for consumers also frees up discretionary income for increased consumptive spending.

On the other hand, new renewable energy and climate change mitigation technology (such as artificial photosynthesis) has been argued to promote a prolonged era of human stewardship over ecosystems known as the Sustainocene.

In the Sustainocene, "instead of the cargo-cult ideology of perpetual economic growth through corporate pillage of nature, globalised artificial photosynthesis will facilitate a steady state economy and further technological revolutions such as domestic nano-factories and e-democratic input to local communal and global governance structures.