Unification Decree (Spain, 1937)

The military conspirators of 1936 did not produce any clear vision of a political regime which would follow the coup; in the short run, some administrative powers were to stay with provincial civil committees, composed of most representative or most committed individuals.

The largest grouping, CEDA, which held 88 seats in the Cortes, had been gradually disintegrating since the February elections; its structures had partially collapsed, having been abandoned by militants disappointed with the movement's legalist strategy.

The most dynamic political power was Falange; a 1933-born third-rate party known mostly for street violence and as a point of reference for Spanish Fascism, in the atmosphere of rapid radicalization of 1936 it attracted tens and soon hundreds of thousands of mostly young people.

[47] Terms of such a unification remained extremely unclear; some like Goicoechea supported a general “patriotic front”,[48] some suggested a personalist “Partido Franquista”[49] and people in caudillo's close entourage like Nicolás Franco preferred rather a civic “Acción Ciudadana”.

[50] All these concepts were resemblant of Primo de Rivera state party, Unión Patriótica, the amorphous and bureaucratic structure built from scratch and organized around general values such as patriotism, discipline, work, law and order.

In December 1936 the military propaganda enforced the “Una Patria Un Estado Un Caudillo” slogan, made mandatory in sub-titles of all newspapers issued in the Nationalist zone, including the Falangist and the Carlist ones.

[57] In February he also ventured to offer some thoughts on “ideologia nacional”; having ignored all other groupings he suggested it should possibly be founded on Falangism and Traditionalism, though he also rejected the idea of reproducing a Fascist scheme.

[58] During late winter and early spring of 1937 Franco talked to Italian Fascist heavyweights Farinacci, Cantalupo and Danzi; all tried to inspire him towards a long-term solution modelled after Italy, based on the concept of a monopolist Partido Nacional Español state party.

[59] It seems that at that time he expected that the Falangists and the Carlists would work out the merger terms themselves; in a letter to Rome Nicolás Franco claimed that both parties were in midst of negotiations, that the talks were going on well and that the major problem was Don Javier, unwilling to cede power.

Contemporary scholar concludes that Franco considered the Falangists tamed and viewed the Carlists, as usual inflexible and intransigent, as the chief obstacle;[60] he was also increasingly irritated by their “tono de soberanía”.

[66] While politicians and front-line militias remained on at least correct if not amicable terms,[67] in the rear fistfights and clashes between Carlists and Falangists were by no means rare and at times they escalated into gunfights; they mutually sabotaged their rallies[68] and denounced each other to military authorities.

Exchange of public statements at the turn of 1936 and 1937 immediately revealed major differences: an article by Carlist pundit presented both as partners,[70] but in response[71] Hedilla declared that Traditionalists were most likely to be absorbed by Falange.

[79] Though the Alfonsists were not admitted they realized what was going on; their most active politicians, José María Areilza and Pedro Sainz-Rodriguez, kept advocating unification in talks with both FE and CT men, apparently calculating that within a multi-party merger they would be better off than marginalized outside the new organization.

[83] The process gained momentum in late winter of 1937; most scholars relate it to arrival of Ramón Serrano Suñer, the astute man impressed with Italian Fascism who immediate replaced conventional Nicolas Franco as Caudillo's key adviser.

[84] Generalísimo was also increasingly concerned with both Falange and Carlism assuming a bolder tone; in March Don Javier[85] and Hedilla[86] addressed him with letters which blended declarations of loyalty with demands, while Falangist congresses drafted grand schemes which demonstrated designs for political hegemony.

[100] At 10:30 PM the same day, April 18,[101] Franco announced the unification in a radio broadcast;[102] The long speech[103] was formatted as historiosophic lecture on Spanish past with special attention paid to national unity as maintained throughout centuries.

Referring to “nuestro movimiento” the speech at one point hailed great contribution of Falange, Traditionalism and “otras fuerzas” to note that “we have decided to finalize this unifying work”,[104] to revert to grandiloquent paragraphs later on.

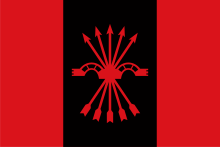

[112] One more decree followed shortly; it defined salute, insignia, anthem, banner, slogan and address code; it also allowed party militias incorporated into the army to use their own symbols until the end of the war.

However, they were sounded on some issues; Franco changed the set of his original Carlist appointees to the Junta in line with Rodezno's advice[126] and he discussed with Hedilla the name of the party, with “Falange Española de Tradición” a viable option as late as mid-April.

[140] Most other politicians complied; Gil-Robles ordered dissolution of Acción Popular[141] while Yanguas and Goicoechea declared their total support;[142] it was only the JAP commander Luciano de la Calzada who protested and was condemned to internal exile.

[148] The post of temporary secretary went to López Bassa; other most active figures in the Junta turned out to be Fernando González Vélez (a Falangist old-shirt appointed in place of Hedilla) and Giménez Caballero.

[166] Unlike in case of Carlism no effort was made to maintain original, independent structures; a so-called Falange Española Auténtica, active in the late 1937-1939, were loose tiny groups of third-rate dissidents.

[174] In the second half of 1937 many Carlist local leaders who initially engaged in the emerging FET structures were now bombarding their men in Junta Política with letters of outrage,[175] complaining about lack of Falangist give and take and demanding immediate intervention.

There were 24 Falangists appointed, this time including many “legitimists”;[179] among 12 Carlists there were mostly Rodeznistas but also Fal Conde and few of his followers; the list contained 8 Alfonsists, some of them eminent, 5 high-ranking military men and 1 former CEDA politician, Serrano Suñer.

Key Falangist and Carlist assets – volunteer militia units, formally incorporated into the army but still maintaining their political identity and in mid-1937 amounting to 95,000 men[182] - remained loyal to the military leadership.

[187] Instead of unification, the merger turned into Franco-domesticated Falange absorbing Carlist offshoots,[188] who either (like Iturmendi) renounced their former identity or (like Bilbao) retained it as vague general outlook or (like Rodezno) withdrew after some time anyway.

[195] Eventually FET was formatted along syndicalist lines and in the Francoist Spain it turned into merely one of many groupings competing for power; other of these so-called political families included the Alfonsists, the Carlists, the military, the technocrats, the Church and the bureaucracy.

It is not entirely clear whether unification was a hastily rushed provisional measure triggered by displays of Falangist and Carlist ambitions or rather a carefully prepared step which had matured in Franco's mind for some time.

[202] It is open to debate whether FET was initially intended to harbor a generally vague political program so that doctrinal rigidity did not stand in the way of getting “neutral mass” affiliated, or whether it was formatted along national-syndicalist lines.

[206] Similarly, there is no agreement whether unification broke the backbone of Carlism and commenced its long period of agony, or whether it merely severely weakened the movement which later regained some strength, in the 1960s again started to pose challenge to Franco's political designs, and collapsed due to profound social changes of late Francoism.