United Kingdom invocation of Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union

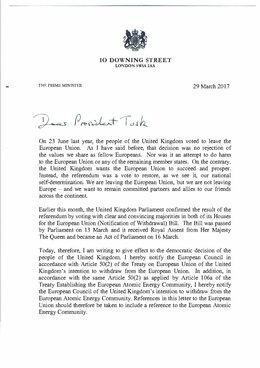

Consequently, the European Union (Notification of Withdrawal) Act 2017 empowering the prime minister to invoke Article 50 was enacted in March 2017.

[3][4] This was extended by two weeks to give the Parliament of the United Kingdom time to reconsider its rejection of the agreement on withdrawal conditions, particularly in the House of Commons.

"[8] Although Cameron stated during the campaign that he would invoke Article 50 straight away in the event of a leave victory,[9] he refused to allow the Civil Service to make any contingency plans, something the Foreign Affairs Select Committee later described as "an act of gross negligence".

Following the referendum result, Cameron announced before the Conservative Party conference that he would resign by October, and that it would be for the incoming prime minister to invoke Article 50.

Article 50 provides an invocation procedure whereby a member can notify the European Council and there is a negotiation period of up to two years, after which the treaties cease to apply with respect to that member—although a leaving agreement may be agreed by qualified majority voting.

[16] Unless the Council of the European Union unanimously agrees to extensions, the timing for the UK leaving under the article is the mandatory period ending at the second anniversary of the country giving official notice to the EU.

[22] Nicolas J. Firzli of the World Pensions Council (WPC) argued in July 2016 that it could be in Britain's national interest to proceed slowly in the following months; Her Majesty's Government might want to push Brussels to accept the principles of a free trade deal before invoking Article 50, hopefully gaining support from some other member states whose economy is strongly tied to the UK, thus "allowing a more nimble union to focus on the free trade of goods and services without undue bureaucratic burdens, modern antitrust law and stronger external borders, leaving the rest to member states".

[23] May confirmed that discussions with the EU would not start in 2016: "I want to work with ... the European council in a constructive spirit to make this a sensible and orderly departure", she said.

At a meeting of the Heads of Government of the other states in June 2016, leaders decided that they would not start any negotiation before the UK formally invoked Article 50.

For example, on 29 June 2016, Tusk told the UK that they would not be allowed access to the European Single Market unless they accept its four freedoms of goods, capital, services, and people.

Issues relating to immigration, free trade, the freedom of movement, the Irish border, intelligence-sharing and financial services will also be discussed.

[34] During the referendum David Cameron stated that, "If the British people vote to leave, [they] would rightly expect [the invoking of Article 50] to start straight away",[35] and there was speculation[by whom?]

In June 2016 he said: "There needs to be a notification by the country concerned of its intention to leave (the EU), hence the request (to British Prime Minister David Cameron) to act quickly.

"[42] In addition, the remaining EU leaders issued a joint statement on 26 June 2016 regretting but respecting Britain's decision and asking them to proceed quickly in accordance with Article 50.

The statement also added: "We stand ready to launch negotiations swiftly with the United Kingdom regarding the terms and conditions of its withdrawal from the European Union.

"[43] An EU Parliament motion passed on 28 June 2016 called for the UK immediately to trigger Article 50 and start the exit process.

"I want to work with ... the European Council in a constructive spirit to make this a sensible and orderly departure" she said "All of us will need time to prepare for these negotiations and the United Kingdom will not invoke article 50 until our objectives are clear".

Three distinct groups of citizens – one supported by crowd funding – brought a case before the High Court of England and Wales to challenge the government's interpretation of the law.

[54] On 3 November 2016, the High Court ruled[55] in R (Miller) v Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union that only Parliament could make the decision on when or indeed whether to invoke Article 50.

[61] The Supreme Court also ruled that devolved legislatures in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland have no legal right to veto the act.

[62] In February 2017, the High Court rejected a claim of several people against the Secretary of State centred on the UK's links with the European Economic Area.

[71] According to David Davis, when presenting the European Union (Notification of Withdrawal) Act 2017: "It is not a Bill about whether the UK should leave the European Union or, indeed, about how it should do so; it is simply about Parliament empowering the Government to implement a decision already made – a point of no return already passed", further saying that the Bill was "the beginning of a process to ensure that the decision made by the people last June is honoured".

50 includes no express provision for revocation of the UK notice, it is clearly arguable for example on the grounds of the duties of sincere cooperation between member states (Art.

"[82] US law professor Jens Dammann argues: "there are strong policy reasons for allowing a Member State to rescind its declaration of withdrawal until the moment that the State's membership in the European Union actually ends" and "there are persuasive doctrinal arguments justifying the recognition of such a right as a matter of black letter law".

[83] EU politicians have said that if the UK changes its mind, they are sure a political formula will be found to reverse article 50, regardless of the technical specifics of the law.

"[86] Similarly, the European Parliament Brexit committee headed by Guy Verhofstadt has stated that "a revocation of notification [by Article 50] needs to be subject to conditions set by all EU27, so that it cannot be used as a procedural device or abused in an attempt to improve on the current terms of the United Kingdom's membership".

[93] On 4 December 2018, the responsible Advocate General to the ECJ published his preliminary opinion that a country could unilaterally cancel its withdrawal from the EU should it wish to do so, by simple notice, prior to actual departure.

[97] Article 50 allows the maximum negotiation period of two years to be extended by a unanimous decision by the European Council and the state in question.