Multistage rocket

Each successive stage can also be optimized for its specific operating conditions, such as decreased atmospheric pressure at higher altitudes.

In the typical case, the first-stage and booster engines fire to propel the entire rocket upwards.

One of the most common measures of rocket efficiency is its specific impulse, which is defined as the thrust per flow rate (per second) of propellant consumption:[3] When rearranging the equation such that thrust is calculated as a result of the other factors, we have: These equations show that a higher specific impulse means a more efficient rocket engine, capable of burning for longer periods of time.

For most non-final stages, thrust and specific impulse can be assumed constant, which allows the equation for burn time to be written as: Where

The velocity and altitude of the rocket after burnout can be easily modeled using the basic physics equations of motion.

The mass of the stage transfer hardware such as initiators and safe-and-arm devices are very small by comparison and can be considered negligible.

For modern day solid rocket motors, it is a safe and reasonable assumption to say that 91 to 94 percent of the total mass is fuel.

[3] It is also important to note there is a small percentage of "residual" propellant that will be left stuck and unusable inside the tank, and should also be taken into consideration when determining amount of fuel for the rocket.

Determining the ideal mixture ratio is a balance of compromises between various aspects of the rocket being designed, and can vary depending on the type of fuel and oxidizer combination being used.

For example, a mixture ratio of a bipropellant could be adjusted such that it may not have the optimal specific impulse, but will result in fuel tanks of equal size.

This would yield simpler and cheaper manufacturing, packing, configuring, and integrating of the fuel systems with the rest of the rocket,[3] and can become a benefit that could outweigh the drawbacks of a less efficient specific impulse rating.

But suppose the defining constraint for the launch system is volume, and a low density fuel is required such as hydrogen.

This example would be solved by using an oxidizer-rich mixture ratio, reducing efficiency and specific impulse rating, but will meet a smaller tank volume requirement.

Two common methods of determining this perfect ΔV partition between stages are either a technical algorithm that generates an analytical solution that can be implemented by a program, or simple trial and error.

[5] It also eliminates the need for ullage motors, as the acceleration from the nearly spent stage keeps the propellants settled at the bottom of the tanks.

Continuing with the previous example, the end of the first stage which is sometimes referred to as 'stage 0', can be defined as when the side boosters separate from the main rocket.

This allows the use of lower pressure combustion chambers and engine nozzles with optimal vacuum expansion ratios.

Upper stages, such as Fregat, used primarily to bring payloads from low Earth orbit to GTO or beyond are sometimes referred to as space tugs.

This is generally not practical for larger space vehicles, which are assembled off the pad and moved into place on the launch site by various methods.

Spent upper stages of launch vehicles are a significant source of space debris remaining in orbit in a non-operational state for many years after use, and occasionally, large debris fields created from the breakup of a single upper stage while in orbit.

[12] Passivation means removing any sources of stored energy remaining on the vehicle, as by dumping fuel or discharging batteries.

[14] The British scientist and historian Joseph Needham points out that the written material and depicted illustration of this rocket come from the oldest stratum of the Huolongjing, which can be dated roughly 1300–1350 AD (from the book's part 1, chapter 3, page 23).

It was proposed by medieval Korean engineer, scientist and inventor Ch'oe Mu-sŏn and developed by the Firearms Bureau (火㷁道監) during the 14th century.

[17] There are records that show Korea kept developing this technology until it came to produce the Singijeon, or 'magical machine arrows' in the 16th century.

The earliest experiments with multistage rockets in Europe were made in 1551 by Austrian Conrad Haas (1509–1576), the arsenal master of the town of Hermannstadt, Transylvania (now Sibiu/Hermannstadt, Romania).

Separation of each portion of a multistage rocket introduces additional risk into the success of the launch mission.

Pyrotechnic fasteners, or in some cases pneumatic systems like on the Falcon 9 Full Thrust, are typically used to separate rocket stages.

A two-stage-to-orbit (TSTO) or two-stage rocket launch vehicle is a spacecraft in which two distinct stages provide propulsion consecutively in order to achieve orbital velocity.

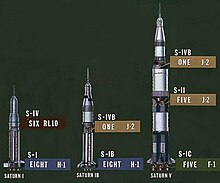

In these designs, the boosters and first stage fire simultaneously instead of consecutively, providing extra initial thrust to lift the full launcher weight and overcome gravity losses and atmospheric drag.

In these designs, the boosters and first stage fire simultaneously instead of consecutively, providing extra initial thrust to lift the full launcher weight and overcome gravity losses and atmospheric drag.