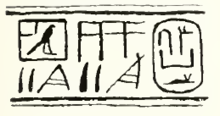

Userkaf

The Old Kingdom royal annals record offerings of beer, bread and lands to various gods, some of which may correspond to building projects on Userkaf's behalf, including the temple of Montu in El-Tod where he is the earliest attested pharaoh.

[9][25][26] Egyptologist Miroslav Verner proposes that he was a son of Menkaure by one of his secondary queens[note 2] and possibly a full brother to his predecessor and the last king of the Fourth Dynasty, Shepseskaf.

[12][42] Alternatively, Userkaf could have been the high priest of Ra before ascending the throne, giving him sufficient influence to marry Shepseskaf's widow in the person of Khentkaus I.

[note 6][49][50] Many Egyptologists, including Verner, Zemina, David, and Baker, believe that Sahure was Userkaf's son rather than his brother as suggested by the Westcar papyrus.

[note 7][60] The latest legible year recorded on the annals for Userkaf is that of his third cattle count, to evaluate the amount of taxes to be levied on the population.

According to the Byzantine scholar George Syncellus, Africanus wrote that the Aegyptiaca mentioned the succession "Usercherês → Sephrês → Nefercherês" at the start of the Fifth Dynasty.

[95] Further evidence for religious activities taking place at the time is given by a royal decree[97] found in the mastaba of the administration official Nykaankh buried at Tihna al-Jabal in Middle Egypt.

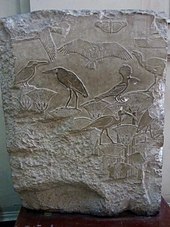

[3] Userkaf's reign might have witnessed the birth of direct trade between Egypt and its Aegean neighbors as shown by a series of reliefs from his mortuary temple representing ships engaged in what may be a naval expedition.

[note 15][17][111] The head of a colossal larger-than-life sphinx statue of Userkaf, now in the Egyptian Museum, was found in the temple courtyard of his mortuary complex at Saqqara by Cecil Mallaby Firth in 1928.

[114] Kozloff notes the youthful features of Userkaf on most of his representations and concludes that if these are good indications of his age, then he might have come to the throne as an adolescent and died in his early twenties.

[114] Userkaf is the first[3][27] pharaoh to build a dedicated temple to the sun god Ra in the Memphite necropolis north of Abusir, on a promontory on the desert edge[14] just south of the modern locality of Abu Gurab.

[116] In any case, Userkaf's successors for the next 80 years followed his course of action:[83] sun temples were built by all subsequent Fifth Dynasty pharaohs until Menkauhor Kaiu, with the possible[118] exception of Shepseskare, whose reign might have been too short to build one.

[125] For the Egyptologist Hans Goedicke, Userkaf's decision to build a temple for the setting sun separated from his own mortuary complex is a manifestation of and response to sociopolitical tensions, if not turmoil, at the end of the Fourth Dynasty.

[126] Thus, Userkaf's pyramid would be isolated in Saqqara, not even surrounded by a wider cemetery for his contemporaries, while the sun temple would serve the social need for a solar cult, which, while represented by the king, would not be exclusively embodied by him anymore.

They propose that Userkaf may have chosen this name to emphasise the victorious and unifying nature of the cult of Ra[128][129] or, at least, to represent some symbolic meaning in relation to kingship.

[130][131] Its true nature was recognised by Ludwig Borchardt in the early 20th century but it was only thoroughly excavated from 1954 until 1957 by a team including Hanns Stock, Werner Kaiser, Peter Kaplony, Wolfgang Helck, and Herbert Ricke.

[138] Construction works on the Nekhenre did not stop with Userkaf's death but continued in at least four building phases, the first of which may have taken place under Sahure,[139] and then under his successors Neferirkare Kakai and Nyuserre Ini.

Instead its main temple seems to have comprised a rectangular enclosure wall with a high mast set on a mound in its center, possibly as a perch for the sun god's falcon.

[137] In addition to these sacrifices Userkaf endowed his sun temple with vast agricultural estates amounting to 34,655 acres (14,024 ha) of land,[38] which Klaus Baer describes as "an enormous and quite unparalleled gift for the Old Kingdom".

[142] Kozloff sees these decisions as a manifestation of Userkaf's young age and of the power of the priesthood of Ra rather than as a result of his personal devotion to the sun god.

[126][143] This decision, probably political,[2] may be connected to the return to the city of Memphis as center of government,[126] of which Saqqara to the west is the necropolis, as well as a desire to rule according to principles and methods closer to Djoser's.

[126] Hence, Userkaf's choice of Saqqara is a manifestation of a return to a "harmonious and altruistic"[126] notion of kingship which Djoser seemed to have symbolized, against that represented by Khufu who had almost personally embodied the sun-god.

[147] The reduced size of the pyramid as compared to those of Userkaf's Fourth Dynasty predecessors owes much to the rise of the cult of Ra which diverted spiritual and financial resources away from the king's burial.

[149] Rainer Stadelmann believes that the reason for the choices of location and layout were practical and due to the presence of the necropolis's administrative center on the north-east corner of Djoser's complex.

Although no name has been identified in the pyramid proper, its owner is believed by Egyptologists including Cecil Mallaby Firth, Bernard Grdseloff, Audran Labrousse (fr), Jean-Philippe Lauer and Tarek El-Awady to have been Neferhetepes, mother of Sahure and in all probability Userkaf's consort.

[153] The core of the main and cult pyramids were built with the same technique, consisting of three[154] horizontal layers of roughly hewn local limestone blocks and gypsum mortar.

The temple entrance led to an open pillared courtyard, stretching from east to west, where the ritual cleaning and preparation of the offerings took place.

His cult was state-sponsored and relied on goods for offerings produced in dedicated agricultural estates established during his lifetime, as well as such resources as fabrics brought from the "house of silver" (the treasury).

[167][168] The mortuary temple of Userkaf must have been in ruins or dismantled by the time of the Twelfth Dynasty as indicated, for example, by a block showing the king performing a ritual found re-used as a construction material in the pyramid of Amenemhat I.

[73] Egyptian Nobel Prize for Literature-laureate Naguib Mahfouz published a short story in 1945 about Userkaf entitled "Afw al-malik Usirkaf: uqsusa misriya".