Catherine de' Medici's building projects

But it wasn't until her husband King Henry's death in 1559, when she found herself at forty the effective ruler of France, that Catherine came into her own as a patron of architecture.

[5] Though she spent colossal sums on the building and embellishment of monuments and palaces, little remains of Catherine's investment today: one Doric column, a few fragments in the corner of the Tuileries Garden, an empty tomb at Saint-Denis.

[1] "As the daughter of the Medici," suggests French art historian Jean-Pierre Babelon, "she was driven by a passion to build and a desire to leave great achievements behind her when she died.

[7] After moving to Rome in 1530, she lived, surrounded by classical and Renaissance treasures, at another Medici palace (now called the Palazzo Madama).

He began extension works at the Louvre Palace,[13] He added a wing to the old castle at Blois, and built the vast château of Chambord, which he showed off to Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor in 1539.

[15] Featuring frescoes and high-relief stucco in the shape of parchment or curled leather strapwork, it became the dominant decorative fashion in France in the second half of the sixteenth century.

In 1562, a long poem by Nicolas Houël likened Catherine to Artemisia, who had built the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, as a tomb for her dead husband.

In his dedication to L'Histoire de la Royne Arthémise, he told Catherine: You will find here the edifices, columns, and pyramids that she had built both at Rhodes and Halicarnassus, which will serve as remembrances for those who reflect on our times and who will be astounded at your own buildings–the palaces at the Tuileries, Montceaux, and Saint-Maur, and the infinity of others that you have constructed, built, and embellished with sculptures and beautiful paintings.

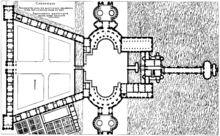

[22]In memory of Henry II, Catherine decided to add a new chapel to the Basilica of Saint-Denis, where the kings of France were traditionally buried.

[23] The plan was to integrate the tomb's effigies of the king and queen with other statues throughout the chapel, creating a vast spatial composition.

[25] Primaticcio's circular design solved the problems faced by the Giusti brothers and Philibert de l'Orme, who had built previous royal tombs.

[26] Art historian Henri Zerner has called the plan "a grand ritualistic drama which would have filled the rotunda's celestial space".

[28] Du Cerceau made minor alterations to Bullant's designs and completed the walls to the top of the second story when construction was abandoned in 1585.

Their poses echo those on the nearby tombs of Louis XII and Francis I. Pilon's feel for the material, however, invests his statues with a greater sense of movement.

[40] This work owes a clear debt to Michelangelo, who had designed the tomb and funerary statues for Catherine's father at the Medici Chapels in Florence.

Earlier French sculpture seems to have influenced him less than Primaticcio's decorations at Fontainebleau:[38] the work of his predecessor Jean Goujon, for example, is more linear and classical.

[44] Catherine's earliest building project was the Château de Montceaux-en-Brie, near Paris, which Henry II gave her in 1556, three years before his death.

Yet all architects have not followed that [principle], shown in Vitruvius's text ... accordingly I have made use, at the palace of Her Majesty the Queen, of the Ionic order, on the view that it is delicate and of greater beauty than the Doric, and more ornamented and enriched with distinctive features.

[56] Only a part of de l'Orme's scheme was ever built: the lower section of a central pavilion, containing an oval staircase, and a wing on either side.

According to Thomson, "The surviving portions of the palace scattered between the Tuileries gardens, the courtyards of the École des Beaux-Arts [Paris] and the Château de la Punta in Corsica show that the columns, pilasters, dormers and tabernacles of the Tuileries were the outstanding masterpieces of non-figurative French Renaissance architectural sculpture".

Architectural historian David Thomson suggests that the oval halls within du Cerceau's courtyards were Catherine de' Medici's idea.

[59] Du Cerceau's drawings reveal that, before he published them in 1576, Catherine decided to join the Louvre to the Tuileries by a gallery running west along the north bank of the Seine.

[48] In June 1572, Charles IX of France brought English diplomats to the gardens to "see the designs of his mother", and they dined in a slated-roofed open-sided pavilion or banqueting house.

[63] According to the French military leader Marshal Tavannes, it was in the Tuileries Garden that she planned the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre, in which thousands of Huguenots were butchered in Paris.

This was a grand ball for the Polish envoys who had come to offer the crown of Poland to her son, the duke of Anjou, later Henry III of France.

She bought this building, on which Philibert de l'Orme had worked, from the heirs of Cardinal Jean du Bellay, after the latter's death in 1560.

The Château de Saint-Maur, still in the possession of the Condé family, was nationalised during the French Revolution, emptied of its contents, and its terrains divided up among real-estate speculators.

[10] Engravings made by Israel Silvestre in about 1650 and a plan from about 1700 show that the Hôtel de la Reine possessed a central wing, a courtyard, and gardens.

[86] Catherine spent ruinous sums of money on buildings at a time of plague, famine, and economic hardship in France.

Pierre de Ronsard captured the mood in a poem: The queen must cease building, Her lime must stop swallowing our wealth...

architect: Philibert de l'Orme