Variable-mass system

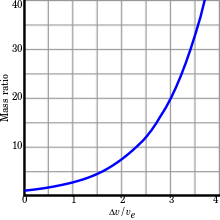

[3] In astrodynamics, which deals with the mechanics of rockets, the term vrel is often called the effective exhaust velocity and denoted ve.

Thus during dt the momentum of the system varies for Relative velocity vrel of the ablated mass with respect to the mass m is written as Therefore, change in momentum can be written as Therefore, by Newton's second law Therefore, the final equation can be arranged as By the definition of acceleration, a = dv/dt, so the variable-mass system motion equation can be written as In bodies that are not treated as particles a must be replaced by acm, the acceleration of the center of mass of the system, meaning Often the force due to thrust is defined as

so that This form shows that a body can have acceleration due to thrust even if no external forces act on it (Fext = 0).

Note finally that if one lets Fnet be the sum of Fext and Fthrust then the equation regains the usual form of Newton's second law: The ideal rocket equation, or the Tsiolkovsky rocket equation, can be used to study the motion of vehicles that behave like a rocket (where a body accelerates itself by ejecting part of its mass, a propellant, with high speed).

It can be derived from the general equation of motion for variable-mass systems as follows: when no external forces act on a body (Fext = 0) the variable-mass system motion equation reduces to[2] If the velocity of the ejected propellant, vrel, is assumed have the opposite direction as the rocket's acceleration, dv/dt, the scalar equivalent of this equation can be written as from which dt can be canceled out to give Integration by separation of variables gives By rearranging and letting Δv = v1 - v0, one arrives at the standard form of the ideal rocket equation: where m0 is the initial total mass, including propellant, m1 is the final total mass, vrel is the effective exhaust velocity (often denoted as ve), and Δv is the maximum change of speed of the vehicle (when no external forces are acting).