Vector-valued function

A common example of a vector-valued function is one that depends on a single real parameter t, often representing time, producing a vector v(t) as the result.

In terms of the standard unit vectors i, j, k of Cartesian 3-space, these specific types of vector-valued functions are given by expressions such as

The vector r(t) has its tail at the origin and its head at the coordinates evaluated by the function.

Closely related is the affine case (linear up to a translation) where the function takes the form

The linear case arises often, for example in multiple regression,[clarification needed] where for instance the n × 1 vector

of predicted values of a dependent variable is expressed linearly in terms of a k × 1 vector

in which X (playing the role of A in the previous generic form) is an n × k matrix of fixed (empirically based) numbers.

The partial derivative of a vector function a with respect to a scalar variable q is defined as[1]

The vectors e1, e2, e3 form an orthonormal basis fixed in the reference frame in which the derivative is being taken.

If the vector a is a function of a number n of scalar variables qr (r = 1, ..., n), and each qr is only a function of time t, then the ordinary derivative of a with respect to t can be expressed, in a form known as the total derivative, as[1]

Some authors prefer to use capital D to indicate the total derivative operator, as in D/Dt.

Whereas for scalar-valued functions there is only a single possible reference frame, to take the derivative of a vector-valued function requires the choice of a reference frame (at least when a fixed Cartesian coordinate system is not implied as such).

The derivative functions in different reference frames have a specific kinematical relationship.

As shown previously, the first term on the right hand side is equal to the derivative of a in the reference frame where e1, e2, e3 are constant, reference frame E. It also can be shown that the second term on the right hand side is equal to the relative angular velocity of the two reference frames cross multiplied with the vector a itself.

[1] Thus, after substitution, the formula relating the derivative of a vector function in two reference frames is[1]

where NωE is the angular velocity of the reference frame E relative to the reference frame N. One common example where this formula is used is to find the velocity of a space-borne object, such as a rocket, in the inertial reference frame using measurements of the rocket's velocity relative to the ground.

The velocity NvR in inertial reference frame N of a rocket R located at position rR can be found using the formula

where NωE is the angular velocity of the Earth relative to the inertial frame N. Since velocity is the derivative of position, NvR and EvR are the derivatives of rR in reference frames N and E, respectively.

where EvR is the velocity vector of the rocket as measured from a reference frame E that is fixed to the Earth.

matrix called the Jacobian matrix of f. If the values of a function f lie in an infinite-dimensional vector space X, such as a Hilbert space, then f may be called an infinite-dimensional vector function.

If the argument of f is a real number and X is a Hilbert space, then the derivative of f at a point t can be defined as in the finite-dimensional case:

If X is a Hilbert space, then one can easily show that any derivative (and any other limit) can be computed componentwise: if

However, the existence of a componentwise derivative does not guarantee the existence of a derivative, as componentwise convergence in a Hilbert space does not guarantee convergence with respect to the actual topology of the Hilbert space.

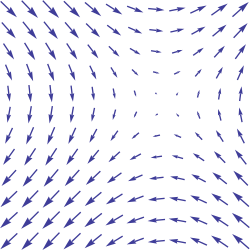

Vector fields are often used to model, for example, the speed and direction of a moving fluid throughout three dimensional space, such as the wind, or the strength and direction of some force, such as the magnetic or gravitational force, as it changes from one point to another point.

The elements of differential and integral calculus extend naturally to vector fields.

When a vector field represents force, the line integral of a vector field represents the work done by a force moving along a path, and under this interpretation conservation of energy is exhibited as a special case of the fundamental theorem of calculus.

A vector field is a special case of a vector-valued function, whose domain's dimension has no relation to the dimension of its range; for example, the position vector of a space curve is defined only for smaller subset of the ambient space.

Likewise, n coordinates, a vector field on a domain in n-dimensional Euclidean space

can be represented as a vector-valued function that associates an n-tuple of real numbers to each point of the domain.

Vector fields are often discussed on open subsets of Euclidean space, but also make sense on other subsets such as surfaces, where they associate an arrow tangent to the surface at each point (a tangent vector).