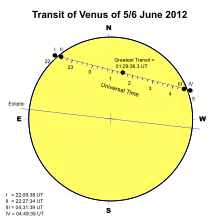

Transit of Venus

During a transit, Venus is visible as a small black circle moving across the face of the Sun.

[citation needed][note 1] Sequences of transits usually repeat every 243 years, after which Venus and Earth have returned to nearly the same point in their respective orbits.

Other patterns are possible within the 243-year cycle, because of the slight mismatch between the times when the Earth and Venus arrive at the point of conjunction.

[2] Ancient Indian, Greek, Egyptian, Babylonian, and Chinese observers knew of Venus and recorded the planet's motions.

[citation needed] It has been proposed that frescoes found at the Maya site at Mayapan may contain a pictorial representation of the 12th or 13th century transits.

[9] The first recorded observation of a transit of Venus was made by the English astronomer Jeremiah Horrocks from his home at Carr House in Much Hoole, near Preston, on 4 December 1639 (24 November O.S.).

After waiting for most of the day, he eventually saw the transit when clouds obscuring the Sun cleared at about 15:15, half an hour before sunset.

[11][note 2] Horrocks based his calculation on the (false) presumption that each planet's size was proportional to its rank from the Sun, not on the parallax effect as used by the 1761 and 1769 and following experiments.

[citation needed] In 1663, the Scottish mathematician James Gregory had suggested in his Optica Promota that observations of a transit of Mercury, at widely spaced points on the surface of the Earth, could be used to calculate the solar parallax, and hence the astronomical unit by means of triangulation.

[citation needed] In a paper published in 1691, and a more refined one in 1716, Halley proposed that more accurate calculations could be made using measurements of a transit of Venus, although the next such event was not due until 1761 (6 June N.S., 26 May O.S.).

[12] In an attempt to observe the first transit of the pair, astronomers from Britain (William Wales and Captain James Cook), Austria (Maximilian Hell), and France (Jean-Baptiste Chappe d'Auteroche and Guillaume Le Gentil) took part in expeditions to places that included Siberia, Newfoundland, and Madagascar.

Jeremiah Dixon and Charles Mason succeeded in observing the transit at the Cape of Good Hope,[14] but Nevil Maskelyne and Robert Waddington were less successful on Saint Helena, although they put their voyage to good use by trialling the lunar-distance method of finding longitude.

The discovery of the planet’s atmosphere has long been attributed to the Russian scientist Mikhail Lomonosov, after he observed the 1761 transit from the Imperial Academy of Sciences of St.

In Philadelphia, the American Philosophical Society erected three temporary observatories and appointed a committee led by David Rittenhouse.

[26][page needed] Le Gentil spent over eight years travelling in an attempt to observe either of the transits.

[13] Under the influence of the Royal Society, the astronomer Ruđer Bošković travelled to Istanbul, but arrived after the transit had happened.

Lalande challenged the accuracy and authenticity of observations obtained by the Hell expedition, but later wrote an article in Journal des sçavans (1778), in which he retracted his comments.

[28] The participants' observations allowed a calculation of the astronomical unit (AU) of 149,608,708 ± 11,835 kilometres (92,962,541 ± 7,354 miles), which differed from the accepted value by 0.007%.

Measurements made of the apparent diameter of a planet such as Venus during a transit allows scientists to estimate exoplanet sizes.

The Hubble Space Telescope used the Moon as a mirror to study light from the atmosphere of Venus, and so determine its composition.

This approximate conjunction is not precise enough to produce a triplet, as Venus arrives 22 hours earlier each time.

[citation needed] The simultaneous occurrence of transits of Mercury and Venus does occur, but extremely infrequently.

[35] The simultaneous occurrence of a solar eclipse and a transit of Venus is currently possible, but very rare.