Dionysus

[17] Romans identified Bacchus with their own Liber Pater, the "Free Father" of the Liberalia festival, patron of viniculture, wine and male fertility, and guardian of the traditions, rituals and freedoms attached to coming of age and citizenship, but the Roman state treated independent, popular festivals of Bacchus (Bacchanalia) as subversive, partly because their free mixing of classes and genders transgressed traditional social and moral constraints.

[18] It is perhaps associated with Mount Nysa, the birthplace of the god in Greek mythology, where he was nursed by nymphs (the Nysiads),[24] although Pherecydes of Syros had postulated nũsa as an archaic word for "tree" by the sixth century BC.

The procession of the City Dionysia was similar to that of the rural celebrations, but more elaborate, and led by participants carrying a wooden statue of Dionysus, and including sacrificial bulls and ornately dressed choruses.

[140] From Thebes, where he was born, he first went to Delphi where he displayed his "starry body", and with "Delphian girls" took his "place on the folds of Parnassus",[141] then next to Eleusis, where he is called "Iacchus": Strabo, says that Greeks "give the name 'Iacchus' not only to Dionysus but also to the leader-in-chief of the mysteries".

Liber was a native Roman god of wine, fertility, and prophecy, patron of Rome's plebeians (citizen-commoners), and one of the members of the Aventine Triad, along with his mother Ceres and sister or consort Libera.

Livy relates their various outrages against Rome's civil and religious laws and traditional morality (mos maiorum); a secretive, subversive and potentially revolutionary counter-culture.

Modern scholarship treats much of Livy's account with skepticism; more certainly, a Senatorial edict, the Senatus consultum de Bacchanalibus (186 BC) was distributed throughout Roman and allied Italy.

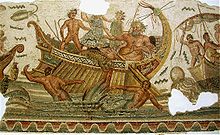

In some Roman sources, the ritual procession of Bacchus in a tiger-drawn chariot, surrounded by maenads, satyrs and drunkards, commemorates the god's triumphant return from the conquest of India.

For example, according to Sallustius, "Jupiter, Neptune, and Vulcan fabricate the world; Ceres, Juno, and Diana animate it; Mercury, Venus, and Apollo harmonize it; and, lastly, Vesta, Minerva, and Mars preside over it with a guarding power.

Three centuries after the reign of Theodosius I which saw the outlawing of pagan worship across the Roman Empire, the 692 Quinisext Council in Constantinople felt it necessary to warn Christians against participating in persisting rural worship of Dionysus, specifically mentioning and prohibiting the feast day Brumalia, "the public dances of women", ritual cross-dressing, the wearing of Dionysiac masks, and the invoking of Bacchus' name when "squeez[ing] out the wine in the presses" or "when pouring out wine into jars".

[179] According to the Lanercost chronicle, during Easter in 1282 in Scotland, the parish priest of Inverkeithing led young women in a dance in honor of Priapus and Father Liber, commonly identified with Dionysus.

[180] Historian C. S. Watkins believes that Richard of Durham, the author of the chronicle, identified an occurrence of apotropaic magic (by making use of his knowledge of ancient Greek religion), rather than recording an actual case of the survival of a pagan ritual.

[218] Several ancient sources record an apparently widespread belief in the classical world that the god worshiped by the Jewish people, Yahweh, was identifiable as Dionysus or Liber via his identification with Sabazios.

According to Nonnus, though Persephone was "the consort of the blackrobed king of the underworld", she remained a virgin, and had been hidden in a cave by her mother to avoid the many gods who were her suitors, because "all that dwelt in Olympos were bewitched by this one girl, rivals in love for the marriageable maid."

He began to change into many different forms in which he returned the attack, including Zeus, Cronus, a baby, and "a mad youth with the flower of the first down marking his rounded chin with black."

[226] The birth narrative given by Gaius Julius Hyginus (c. 64 BC – 17 AD) in Fabulae 167, agrees with the Orphic tradition that Liber (Dionysus) was originally the son of Jove (Zeus) and Proserpine (Persephone).

Hyginus writes that Liber was torn apart by the Titans, so Jove took the fragments of his heart and put them into a drink which he gave to Semele, the daughter of Harmonia and Cadmus, king and founder of Thebes.

Without Bacchos to inspire the dance, its grace was only half complete and quite without profit; it charmed only the eyes of the company, when the circling dancer moved in twists and turns with a tumult of footsteps, having only nods for words, hand for mouth, fingers for voice."

In his letter To the Cynic Heracleios, Julian wrote "I have heard many people say that Dionysus was a mortal man because he was born of Semele and that he became a god through his knowledge of theurgy and the Mysteries, and like our lord Heracles for his royal virtue was translated to Olympus by his father Zeus."

When Zeus decided it was time to impose a new order on humanity, for it to "pass from the nomadic to a more civilized mode of life", he sent his son Dionysus from India as a god made visible, spreading his worship and giving the vine as a symbol of his manifestation among mortals.

"[247] When Dionysus grew up, he discovered the culture of the vine and the mode of extracting its precious juice, being the first to do so;[248] but Hera struck him with madness, and drove him forth a wanderer through various parts of the earth.

Another story of Ampelus was related by Nonnus: in an accident foreseen by Dionysus, the youth was killed while riding a bull maddened by the sting of a gadfly sent by Selene, the goddess of the Moon.

[265][266] This story survives in full only in Christian sources, whose aim was to discredit pagan mythology, but it appears to have also served to explain the origin of secret objects used by the Dionysian Mysteries.

In the latter, Apollodorus tells how after having been hidden away from Hera's wrath, Dionysus traveled the world opposing those who denied his godhood, finally proving it when he transformed his pirate captors into dolphins.

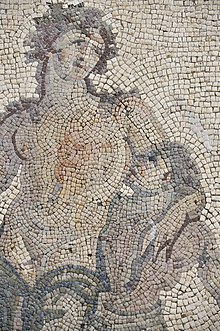

Dionysus is represented by city religions as the protector of those who do not belong to conventional society and he thus symbolizes the chaotic, dangerous and unexpected, everything which escapes human reason and which can only be attributed to the unforeseeable action of the gods.

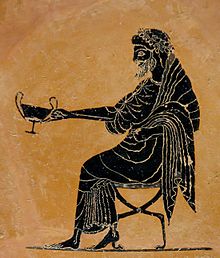

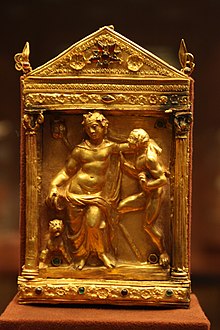

"[318] The fourth-century BC Derveni Krater, the unique survival of a very large scale Classical or Hellenistic metal vessel of top quality, depicts Dionysus and his followers.

Dionysus appealed to the Hellenistic monarchies for a number of reasons, apart from merely being a god of pleasure: He was a human who became divine, he came from, and had conquered, the East, exemplified a lifestyle of display and magnificence with his mortal followers, and was often regarded as an ancestor.

[319] He continued to appeal to the rich of Imperial Rome, who populated their gardens with Dionysian sculpture, and by the second century AD were often buried in sarcophagi carved with crowded scenes of Bacchus and his entourage.

The statue tries to suggest both drunken incapacity and an elevated consciousness, but this was perhaps lost on later viewers, and typically the two aspects were thereafter split, with a clearly drunk Silenus representing the former, and a youthful Bacchus often shown with wings, because he carries the mind to higher places.

J. M. Tolcher's autobiography, Poof (2023), features Dionysus as a character and a force of modern liberation in Australia, incorporating traditional myth and Nietzschean philosophy to represent queer suffering.