Scotland in the modern era

Scotland's economic contribution to the Empire and the Industrial Revolution included its banking system and the development of cotton, coal mining, shipbuilding and an extensive railway network.

Industrialisation and changes to agriculture and society led to depopulation and clearances of the largely rural highlands, migration to the towns and mass emigration, where Scots made a major contribution to the development of countries including the US, Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

In the 20th century, Scotland played a major role in the British and allied effort in the two world wars and began to suffer a sharp industrial decline, going through periods of considerable political instability.

With the advent of the Union with England and the demise of Jacobitism, thousands of Scots, mainly Lowlanders, took up positions of power in politics, civil service, the army and navy, trade, economics, colonial enterprises and other areas across the nascent British Empire.

Much of what is incorporated in the scientific method (the nature of knowledge, evidence, experience, and causation) and some modern attitudes towards the relationship between science and religion were developed by his proteges David Hume and Adam Smith.

He and other Scottish Enlightenment thinkers developed what he called a 'science of man',[12] which was expressed historically in works by authors including James Burnett, Adam Ferguson, John Millar and William Robertson, all of whom merged a scientific study of how humans behave in ancient and primitive cultures with a strong awareness of the determining forces of modernity.

However, Catholic Emancipation in 1829 and the influx of large numbers of Irish immigrants, particularly after the famine years of the late 1840s, principally to the growing lowland centres like Glasgow, led to a transformation of its fortunes.

[21] Merchants who profited from the American trade began investing in leather, textiles, iron, coal, sugar, rope, sailcloth, glassworks, breweries, and soapworks, setting the foundations for the city's emergence as a leading industrial centre after 1815.

The stereotype emerged early on of Scottish colliers as brutish, non-religious and socially isolated serfs;[34] that was an exaggeration, for their life style resembled coal miners everywhere, with a strong emphasis on masculinity, egalitarianism, group solidarity, and support for radical labour movements.

[36] Not only was good passenger service established by the late 1840s, but an excellent network of freight lines reduce the cost of shipping coal, and made products manufactured in Scotland competitive throughout Britain.

[42] The industrial developments, while they brought work and wealth, were so rapid that housing, town-planning, and provision for public health did not keep pace with them, and for a time living conditions in some of the towns and cities were notoriously bad, with overcrowding, high infant mortality, and growing rates of tuberculosis.

[45] In its aftermath the British government enacted a series of laws that attempted to speed the process, including a ban on the bearing of arms, the wearing of tartan and limitations on the activities of the Episcopalian Church.

It was quieted when the government stepped in passing the Crofters' Holdings (Scotland) Act, 1886 to reduce rents, guarantee fixity of tenure, and break up large estates to provide crofts for the homeless.

[70] Historians now accept that very few boys were able to pursue this route to social advancement and that literacy was not noticeably higher than comparable nations, as the education in the parish schools was basic, short and attendance was not compulsory.

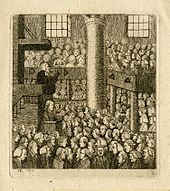

[70] The five Scottish universities had been oriented to clerical and legal training, after the religious and political upheavals of the 17th century they recovered with a lecture-based curriculum that was able to embrace economics and science, offering a high quality liberal education to the sons of the nobility and gentry.

[70] Although Scotland increasingly adopted the English language and wider cultural norms, its literature developed a distinct national identity and began to enjoy an international reputation.

Allan Ramsay (1686–1758) laid the foundations of a reawakening of interest in older Scottish literature, as well as leading the trend for pastoral poetry, helping to develop the Habbie stanza as a poetic form.

His poem (and song) "Auld Lang Syne" is often sung at Hogmanay (the last day of the year), and "Scots Wha Hae" served for a long time as an unofficial national anthem of the country.

Robert Louis Stevenson's work included the urban Gothic novella Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886), and played a major part in developing the historical adventure in books like Kidnapped and Treasure Island.

[96] However, the centralisation of much of the government administration, including the king's works, in London, meant that a number of Scottish architects spent most of all of their careers in England, where they had a major impact on Georgian architecture.

[97] In the 20th century, Scotland made a major contribution to the British participation in the two world wars and suffered relative economic decline, which only began to be offset with the exploitation of North Sea Oil and Gas from the 1970s and the development of new technologies and service industries.

The despair reflected what Finlay (1994) describes as a widespread sense of hopelessness that prepared local business and political leaders to accept a new orthodoxy of centralised government economic planning when it arrived during the Second World War.

John MacLean became a key political figure in what became known as Red Clydeside, and in January 1919, the British Government, fearful of a revolutionary uprising, deployed tanks and soldiers in central Glasgow.

[115] Other writers that emerged in this period, and are often treated as part of the movement, include the poets Edwin Muir and William Soutar, the novelists Neil Gunn, George Blake, Nan Shepherd, A J Cronin, Naomi Mitchison, Eric Linklater and Lewis Grassic Gibbon, and the playwright James Bridie.

[117] In the inter-war period, elements of modernism and the Scottish Renaissance, were incorporated into art by figures including Stanley Cursiter (1887–1976), who was influenced by Futurism, and William Johnstone (1897–1981), whose work marked a move towards abstraction.

[121] The shipyards and heavy engineering factories in Glasgow and Clydeside played a key part in the war effort, and suffered attacks from the Luftwaffe, enduring great destruction and loss of life.

Prime Minister Winston Churchill appointed Labour politician Tom Johnston as Secretary of State for Scotland in February 1941; he controlled Scottish affairs until the war ended.

[108] The introduction in 1989 by the Thatcher-led Conservative government of the Community Charge (widely known as the Poll Tax), one year before the rest of the United Kingdom, contributed to a growing movement for a return to direct Scottish control over domestic affairs.

[115] This period also saw the emergence of a new generation of Scottish poets that became leading figures on the UK stage, including Don Paterson, Robert Crawford, Kathleen Jamie and Carol Ann Duffy.

[151] Since the 1990s, the most commercially successful artist has been Jack Vettriano, whose work usually consists of figure composition, with his most famous painting The Singing Butler (1992), often cited as the best selling print in Britain.