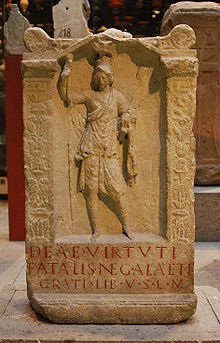

Virtus

It was often divided into different qualities including prudentia (practical wisdom), iustitia (justice), temperantia (temperance, self-control), and fortitudo (courage).

At one time virtus extended to include a wide range of meanings that covered one general ethical ideal.

Virtus was exercised in the pursuit of gloria for the benefit of the res publica resulting in the winning of eternal memoria.

According to D.C. Earl, "Outside the service of the res publica there can be no magistratus and therefore, strictly speaking, no gloria, no nobilitas, no virtus".

Cicero's goal was not to impugn the noble class but widen it to include men who had earned their positions by merit.

Sallust asserted that virtus did not rightfully belong to the nobilitas as a result of their family background but specifically to the novus homo through the exercise of ingenium (talent, also means sharpness of mind, sagacity, foresight, and character).

For Sallust and Cicero alike, virtus comes from winning glory through illustrious deeds (egregia facinora) and the observance of right conduct through bonae artes.

Since virtus was primarily attributed to a full grown man who had served in the military, children were not particularly suited to obtain this particular virtue.

[14] Virtus applies exclusively to a man's behaviour in the public sphere; that is, to the application of duty to the res publica in the cursus honorum.

His private business was no place to earn virtus, even when it involved courage, feats of arms, or other associated qualities performed for the public good.

This title implied that he could make all legal and binding decisions for the family; he also owned all its money, land, and other property.

The only time a son was seen as separate from his father's control in the eyes of other Romans was when he assumed his public identity as a citizen.

Its broad definition led to it being used to describe a number of qualities that the Roman people idealized in their leaders.

Young boys would have learned how to wield weapons and military tactics starting at home with their fathers and older male relatives and later in school.

This propaganda encouraged young boys coming into their manhood to be brave fighters and earn virtus.

By gaining virtus and gloria one could hope to aspire to high political office and great renown.

Such negative characteristics included being shameless, inactive, isolated, or leisurely and were the absence of virtus; placing dignitas into a static, frozen state.

Romans were willing to suffer shame, humiliation, victory, defeat, glory, destruction, success, and failure in pursuit of this.

Virtus was often associated with being aggressive[citation needed] and this could be dangerous in the public sphere and the political world.

Many political offices had an age minimum which ensured that the men filling the positions had the proper amount of experience in the military and in government.

Romans believed "your identity was neither fixed nor permanent, your worth was a moving target, and you had to always be actively engaged in proving yourself.

This system resulted in a strong built-in impetus in Roman society to engage in military expansion and conquest.

[20] Nonetheless, poems such as Catullus 16 and the Carmina Priapea,[21] as well as speeches such as Cicero's In Verrem, demonstrate that manliness and pudicitia, or sexual propriety, were linked.

All else is false and doubtful, ephemeral and changeful: only virtus stands firmly fixed, its roots run deep, it can never be shaken by any violence, never moved from its place.