Faith in Buddhism

However, from the nineteenth century onward, in countries like Sri Lanka and Japan, and also in the West, Buddhist modernism has downplayed and criticized the role of faith in Buddhism.

[25] In contrast to Vedic Brahmanism, which preceded Buddhism, early Buddhist ideas of faith are more connected with the teachings that are learnt and practised, rather than focused on an outward deity.

Reflection on suffering and impermanence leads the devotees to a sense of fear and agitation (saṃvega), which motivates them to take refugee in the Triple Gem and to cultivate faith.

Despite this role, some Indologists such as André Bareau and Lily De Silva believed early Buddhism did not assign the same value to faith as in some other religions, such as Christianity.

[48] He notes that there is a lot of material in the early scriptures emphasizing how important faith is,[49] but argues that "the growth of Buddhist rites and liturgies was surely a wholly unintended consequence of the Buddha's preaching".

Secondly, the taking of refuge honours the truth and efficacy of the Buddha's spiritual doctrine, on subjects including the characteristics of phenomenon (saṅkhāra) such as their impermanence (anicca), and the path to liberation.

[59] Giving an example of such an approach, the Buddha states that the practice of abandoning greed, hatred, and delusion will benefit the practitioner, regardless of whether there is such a thing as karmic retribution and rebirth.

[61] In the discourse called the Canki Sutta, the Buddha points out that people's beliefs may turn out in two different ways: they might either be genuine, factual, and not mistaken; or vain, empty, and false.

[63] Thus, the discourse criticizes, among others, divine revelation, tradition, and report, as leading to "groundless faith" and as being incomplete means of acquiring spiritual knowledge or truth.

[72] The Buddha states in several discourses, including the Vimaṁsaka Sutta, that his disciples should investigate even him as to whether he really is enlightened and pure in conduct, by observing him for a long time.

The sūtra itself describes different types of devotion to it—receiving and keeping, reading, reciting, teaching, and transcribing it—and it was worshiped in a large variety of ways.

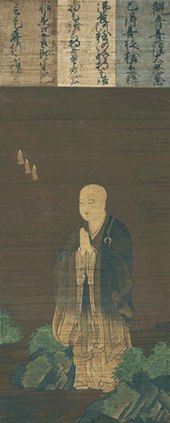

[116] The Chinese Tiantai school (6th century) and its later Japanese form, Tendai, further promoted worship of the Lotus Sūtra, combined with devotion toward Amitābha Buddha.

[118] Some schools of the Kamakura period (12th–14th century), took reverence towards the Lotus Sūtra to the extent that they saw it as the single vehicle or path of the dharma, and the Japanese teacher Nichiren (1222–82) believed only this practice led society to an ideal Buddha land.

[135] Pure Land Buddhist meditations were initially practiced by Huiyuan (334–416 CE) on Mount Lu with the founding of the White Lotus Society.

[137] There were two key often opposing elements of the Pure Land faith in China, the ideals of self-power (referring to a bodhisattva's own efforts and merits) and other-power (the Buddha's vast spiritual power).

Other schools like Tendai, Shingon and Kegon allowed for an approach which made room for self-power and numerous complex meditative practices in traditional monastic settings.

[153] Although early Buddhism already emphasized letting-go of self-conceit by practising the dharma, in the later Pure Land tradition this was drawn further by stating that people should give up all "self-power" and let the power of Amitābha do the work of attaining salvation for them.

Apart from the focus on meditation practice which was common in Zen Buddhism, Dōgen led a revival of interest in the study of the sūtras, which he taught would inspire to a faith based on understanding.

His cult originated in the northern borders of India, but he has been honoured for his compassion in many countries, such as China, Tibet, Japan, Sri Lanka, and other parts of Southeast Asia, and among diverse levels of society.

[170] Focusing on both mundane benefits and salvation, devotion to Avalokiteśvara was promoted through the spread of the Lotus Sūtra, which includes a chapter about him,[171] as well as through the Perfection of Wisdom sūtras.

[178] In the early Pāli scriptures, as well as in some customs in traditional Buddhist societies, traces can still be found of the period during which Buddhism competed with nāga worship and assimilated some of its features.

Such transformation of pre-Buddhist beliefs also explains the popularity of movements like Japanese Pure Land Buddhism under Hōnen and Shinran, even though in their teachings they opposed animism.

China, Burma, and Thailand came to honour him as part of millenarian movements, and they believed that Maitreya Buddha would arise, during times of suffering and crisis, to usher in a new era of happiness.

[188] From the fourteenth century onward, White Lotus sectarianism arose in China, which encompassed beliefs in the coming of Maitreya during an apocalyptic age.

[190] White Lotus millenarian beliefs would prove persistent, and survived into the nineteenth century, when the Chinese associated the coming of Maitreya's age with political revolution.

[185] Nevertheless, faith in the coming of a new era of Maitreya was not just political propaganda to incite rebellion, but was, in the words of Chinese Studies scholar Daniel Overmyer, "rooted in continuously existing cultic life.

[195] Because of the threat from colonial powers and Christianity, and the rise of an urban middle class, at the end of the nineteenth century Sri Lankan Buddhism started to change.

In response to this, Buddhist schools such as Zen developed a movement called "New Buddhism" (shin bukkyo), which emphasized rationalism, modernism, and warrior ideals.

[201] Despite these widespread modernist trends in Asia, scholars have also observed decline of rationalism and resurfacing of pre-modern religious teachings and practices: From the 1980s onward, they observed that in Sri Lankan Buddhism devotional religiosity, magical practices, honouring deities, and moral ambiguity had become more widespread, as the effects of "protestant Buddhism" were becoming weaker.

[206] In contrast to these typical modernist trends, some western Buddhist communities show great commitment to their practice and belief, and for that reason are more traditionally religious than most forms of New Age spirituality.