War of the Pacific

"[41] Also, B. Farcau objects to the argument: "On the other hand, the sorry state of the Chilean armed forces at the outbreak of the war, as will be discussed in the following chapter, hardly supports a theory of conscious, premeditated aggression.

Sater cites the British minister in Lima, Spencer St. John: "the rival parties may try to make political capital out of jealousy for the national honor, and His Excellency [Peruvian President Prado] may be forced to give way to the popular sentiment.

In 1868, a company named Compañía Melbourne Clark was established in Valparaíso, Chile,[54] with 34% British capital[55] provided by Antony Gibbs & Sons of London, which also held shares of salitreras in Peru.

[57] President Mariano Ignacio Prado was "determined to complete the monopoly," and in 1876, Peru bought the nitrate licenses for "El Toco" auctioned by a Bolivian decree of 13 January 1876.

[104] Meanwhile, the Peruvian navy pursued other actions, particularly in August 1879 when the Unión unsuccessfully raided Punta Arenas, near the Strait of Magellan, in an attempt to capture the British merchant ship Gleneg, which was transporting weapons and supplies to Chile.

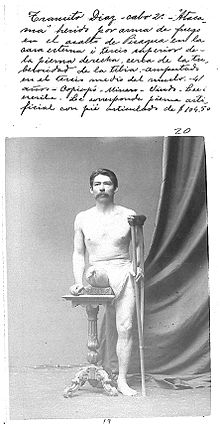

[116] Bruce W. Farcau comments that, "The province of Tarapacá was lost along with a population of 200,000, nearly one tenth of the Peruvian total, and an annual gross income of £28 million in nitrate production, virtually all of the country's export earnings.

As Daza and his officers came to Tacna and Arica, they failed to see the expected Peruvian military strength and understood that their position of power in Bolivia was threatened by a defeat of the Allies.

The Bolivian historian Querejazu suggests that Daza successfully used the Chilean offer of Tacna and Arica for Bolivia to exert pressure on Peru to get a more favorable Protocol of Subsidies.

[124] Piérola has been criticised because of his sectarianism, frivolous investment, bombastic decrees, and lack of control in the budget, but it must be said that he put forth an enormous effort to obtain new funds and to mobilize the country for the war.

Chile demanded Peruvian Tarapacá Province and the Bolivian Atacama, an indemnity of 20,000,000 gold pesos, the restoration of property taken from Chilean citizens, the return of the Rimac, the abrogation of the treaty between Peru and Bolivia, and a formal commitment not to mount artillery batteries in Arica's harbor.

The alternative plan of War Minister José Francisco Vergara laid down a turning movement that would bypass the Peruvian line by attacking from further to the east: through the Lurín valley, moving via Chantay and reaching Lima at Ate.

The new Chilean administration continued to push for an end to the costly war, but contrary to expectations, neither Lima's capture nor the imposition of heavy taxes led Peru to sue for peace.

The resistance was organised by Andrés Avelino Cáceres in the regions Cajamarca (north), Arequipa (south) and the Sierra Central (Cerro Pasco to Ayacucho)[153] However, the collapse of national order in Peru brought on also domestic chaos and violence, most of which was motivated by class or racial divisions.

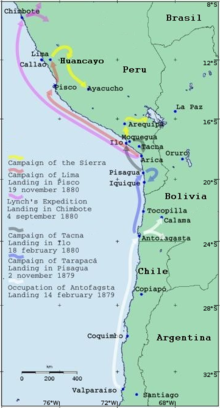

In February 1881, Chilean forces, under Lieutenant Colonel Ambrosio Letelier started the first expedition into the Sierra, with 700 men, to defeat the last guerrilla bands from Huánuco (30 April) to Junín.

[156] To annihilate the guerrillas in the Mantaro Valley, in January 1882, Lynch ordered an offensive with 5,000 men[157] under the command of Gana and Del Canto, first towards Tarma and then southeast towards Huancayo, reaching Izcuchaca.

He issued a manifesto, es:Grito de Montán,[159] calling for peace and in December 1882 convened a convention of representatives of the seven northern departments, where he was elected "Regenerating President"[160][161] To support Iglesias against Montero, on 6 April 1883, Patricio Lynch started a new offensive to drive the guerrillas from central Peru and to destroy Caceres's army.

[97] The Colorados Battalion, President Daza's personal guard, was armed with Remington Rolling Block rifles, but the remainder carried odds and ends including flintlock muskets.

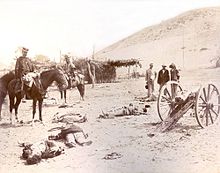

Chilean Navy ships bombarded beach defenses for several hours at dawn, followed by open, oared boats landing army infantry and sapper units into waist-deep water under enemy fire.

Peru and Bolivia fought a defensive war, maneuvering through long overland distances and relied when possible on land or coastal fortifications with gun batteries and minefields.

[194][195] On 2 July 1884, the guerrillero Tomás Laymes and three of his men were executed in Huancayo by Caceres's forces because of the atrocities and crimes committed by the guerrillas against the Peruvian inhabitants of the cities and hamlets.

They were all aware that the only way they could hope to receive payment on their loans and earn the profits from the nitrate business was to see the war ended and trade resumed on a normal footing without legal disputes over ownership of the resources of the region hanging over their heads.

"[199] Nonethelesses, belligerents were able to purchase torpedo boats, arms, and munitions abroad and to circumvent ambiguous neutrality laws, and firms like Baring Brothers in London were not averse to dealing with both Chile and Peru.

The Bolivian Minister in Washington offered US Secretary of State William Maxwell Evarts the prospects of lucrative guano and nitrate concessions to American investors in return for official protection of Bolivia's territorial integrity.

Earlier, Christiancy had written to the US that Peru should be annexed for ten years and then admitted in the Union to provide the United States with access to the rich markets of South America.

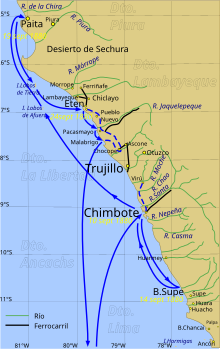

Beside the economic plans, Stephen A. Hurlbut, Christiancy's successor, had negotiated with García Calderón the cession to the US of a naval base in Chimbote and the railroads to the coal mines upcountry.

[204] When it became known that Blaine's representative in Peru, Hurlbut, would personally profit from the settlement, it was clear he was complicating the peace process[205][206] The American attempts reinforced Garcia Calderon's refusal to discuss the matter of territorial cession.

[210] In fact, Sergio Villalobos states that in 1817, the US accepted the confiscation of art works but the 1874 Project of an International Declaration concerning the Laws and Customs of War asserted that the cultural assets were to be considered as protected.

On 4 January 1883, in a session of the Chilean Congress, the deputy Augusto Matte Pérez questioned Minister of the Interior José Manuel Balmaceda on the "opprobrious and humiliating" shipments of Peruvian cultural assets.

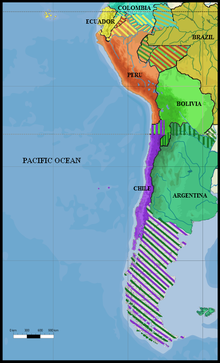

[216] Ever since the war ended, the aspiration to regain coastal sovereignty has been a recurring theme in Bolivia's domestic and foreign policy, as well as a common cause of tensions with Chile.

In this milieu, the vagueness of the boundaries between the three states, coupled with the discovery of valuable guano and nitrate deposits in the disputed territories, combined to produce a diplomatic conundrum of insurmountable proportions.