Kibble balance

A Kibble balance (also formerly known as a watt balance) is an electromechanical measuring instrument that measures the weight of a test object very precisely by the electric current and voltage needed to produce a compensating force.

It is a metrological instrument that can realize the definition of the kilogram unit of mass based on fundamental constants.

After considering alternatives, in 2013 the General Conference on Weights and Measures (CGPM) agreed on accuracy criteria for replacing this definition with one based on the use of a Kibble balance.

After these criteria had been achieved, the CGPM voted unanimously on November 16, 2018, to change the definition of the kilogram and several other units, effective May 20, 2019, to coincide with World Metrology Day.

Then the mass is calculated from the weight by accurately measuring the local Earth's gravity (the net acceleration combining gravitational and centrifugal effects) with a gravimeter.

[10] In 1978 the Mark I watt balance was built at the NPL with Ian Robinson and Ray Smith.

[13] The main weakness of the ampere balance method is that the result depends on the accuracy with which the dimensions of the coils are measured.

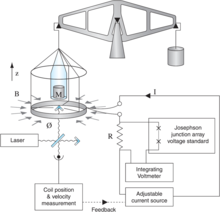

The Kibble balance uses an extra calibration step to cancel the effect of the geometry of the coils, removing the main source of uncertainty.

This extra step involves moving the force coil through a known magnetic flux at a known speed.

[14] Bryan Kibble worked with Ian Robinson and Janet Belliss to build this Mark Two version of the balance.

This design allowed for measurements accurate enough for use in the redefinition of the SI unit of mass: the kilogram.

[16] In 2014, NRC researchers published the most accurate measurement of the Planck constant at that time, with a relative uncertainty of 1.8×10−8.

[18] Other Kibble balance experiments are conducted in the US National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), the Swiss Federal Office of Metrology (METAS) in Berne, the International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM) near Paris and Laboratoire national de métrologie et d’essais (LNE) in Trappes, France.

The entire mechanical subsystem operates in a vacuum chamber to remove the effects of air buoyancy.

The required current is measured, using an ammeter comprising a Josephson junction voltage standard and an integrating voltmeter.

In addition, the balance depends on a highly accurate and precise frequency reference such as an atomic clock to compute voltage and current.

Thus, the precision and accuracy of the mass measurement depends on the Kibble balance, the gravimeter, and the clock.

As of 2019, work is underway to produce standardized devices at prices that permit use in any metrology laboratory that requires high-precision measurement of mass.

These are fabricated on single silicon dies similar to those used in microelectronics and accelerometers, and are capable of measuring small forces in the nanonewton to micronewton range traceably to the SI-defined physical constants via electrical and optical measurements.

Due to their small scale, MEMS Kibble balances typically use electrostatic rather than the inductive forces used in larger instruments.

Lateral and torsional[23] variants have also been demonstrated, with the main application (as of 2019) being in the calibration of the atomic force microscope.

Accurate measurements by several teams will enable their results to be averaged and so reduce the experimental error.

[24] Accurate measurements of electric current and potential difference are made in conventional electrical units (rather than SI units), which are based on fixed "conventional values" of the Josephson constant and the von Klitzing constant,

The current Kibble balance experiments are equivalent to measuring the value of the conventional watt in SI units.

With the constant defined exactly, the Kibble balance is not an instrument to measure the Planck constant, but is instead an instrument to measure mass: Gravity and the nature of the Kibble balance, which oscillates test masses up and down against the local gravitational acceleration g, are exploited so that mechanical power is compared against electrical power, which is the square of voltage divided by electrical resistance.

There are also slight seasonal variations in g at a location due to changes in underground water tables, and larger semimonthly and diurnal changes due to tidal distortions in the Earth's shape (earth tide and polar motion) caused by the Moon and the Sun.

For the most precise work in mass metrology, g is measured using dropping-mass absolute gravimeters that contain an iodine-stabilised helium–neon laser interferometer.

The fringe-signal, frequency-sweep output from the interferometer is measured with a rubidium atomic clock.

Since this type of dropping-mass gravimeter derives its accuracy and stability from the constancy of the speed of light as well as the innate properties of helium, neon, and rubidium atoms, the 'gravity' term in the delineation of an all-electronic kilogram is also measured in terms of invariants of nature—and with very high precision.

For instance, in the basement of the NIST's Gaithersburg facility in 2009, when measuring the gravity acting upon Pt‑10Ir test masses (which are denser, smaller, and have a slightly lower center of gravity inside the Kibble balance than stainless steel masses), the measured value was typically within 8 ppb of 9.80101644 m/s2.