Atomic clock

[2] The accurate timekeeping capabilities of atomic clocks are also used for navigation by satellite networks such as the European Union's Galileo Programme and the United States' GPS.

[7] During the 1930s, the American physicist Isidor Isaac Rabi built equipment for atomic beam magnetic resonance frequency clocks.

This led to the idea of measuring the frequency of an atom's vibrations to keep time much more accurately, as proposed by James Clerk Maxwell, Lord Kelvin, and Isidor Rabi.

[14] In 1949, Alfred Kastler and Jean Brossel[16] developed a technique called optical pumping for electron energy level transitions in atoms using light.

[20] In 1997, the International Committee for Weights and Measures (CIPM) added that the preceding definition refers to a caesium atom at rest at a temperature of absolute zero.

[27] Scientists at NIST developed a quantum logic clock that measured a single aluminum ion in 2019 with a frequency uncertainty of 9.4×10−19.

[28][29] At JILA in September 2021, scientists demonstrated an optical strontium clock with a differential frequency precision of 7.6×10−21 between atomic ensembles[clarification needed] separated by 1 mm.

Accuracy is a measurement of the degree to which the clock's ticking rate can be counted on to match some absolute standard such as the inherent hyperfine frequency of an isolated atom or ion.

Stability describes how the clock performs when averaged over time to reduce the impact of noise and other short-term fluctuations (see precision).

The effect places new and stringent requirements on the LO, which must now have low phase noise in addition to high stability, thereby increasing the cost and complexity of the system.

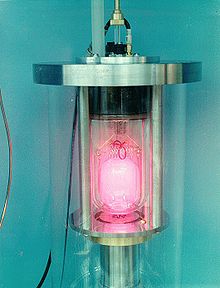

Alternatively, in a caesium or rubidium clock, the beam or gas absorbs microwaves and the cavity contains an electronic amplifier to make it oscillate.

The clocks were the first to use a caesium fountain, which was introduced by Jerrod Zacharias, and laser cooling of atoms, which was demonstrated by Dave Wineland and his colleagues in 1978.

[52][53] The increase in precision from NIST-F1 to NIST-F2 is due to liquid nitrogen cooling of the microwave interaction region; the largest source of uncertainty in NIST-F1 is the effect of black-body radiation from the warm chamber walls.

The evaluation reports of individual (mainly primary) clocks are published online by the International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM).

[55] The International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM) provides a list of frequencies that serve as secondary representations of the second.

In June 2015, the National Physical Laboratory (NPL) in Teddington, UK; the French department of Time-Space Reference Systems at the Paris Observatory (LNE-SYRTE); the German German National Metrology Institute (PTB) in Braunschweig; and Italy's Istituto Nazionale di Ricerca Metrologica (INRiM) in Turin labs started tests to improve the accuracy of satellite comparisons by a factor of 10, but still be limited to one part in 1×1016.

This requires relativistic corrections to be applied to the location of the primary standard which depend on the distance between the equal gravity potential and the rotating geoid of Earth.

[34][66][67][68] In a caesium beam frequency reference, timing signals are derived from a high stability voltage-controlled quartz crystal oscillator (VCXO) that is tunable over a narrow range.

Some commercial applications use a rubidium standard periodically corrected by a global positioning system receiver (see GPS disciplined oscillator).

Most nuclear transitions operate at far too high a freuency to be measured, but the exceptionally low excitation energy of 229mTh produces "gamma rays" in the ultraviolet frequency range.

In 2003, Ekkehard Peik and Christian Tamm[71] noted this makes a clock possible with current optical frequency-measurement techniques.

[81] Although neutral 229mTh atoms decay in microseconds by internal conversion,[82] this pathway is energetically prohibited in 229mTh+ ions, as the second and higher ionization energy is greater than the nuclear excitation energy, giving 229mTh+ ions a long half-life on the order of 103 s.[78] It is the large ratio between transition frequency and isomer lifetime which gives the clock a high quality factor.

In particular the high frequencies and small linewidths of optical clocks promise significantly improved signal-to-noise ratio and instability.

[55] Twenty-first century experimental atomic clocks that provide non-caesium-based secondary representations of the second are becoming so precise that they are likely to be used as extremely sensitive detectors for other things besides measuring frequency and time.

[99][100][101][102] The development of atomic clocks has led to many scientific and technological advances such as precise global and regional navigation satellite systems, and applications in the Internet, which depend critically on frequency and time standards.

[105] The Global Positioning System (GPS) operated by the United States Space Force provides very accurate timing and frequency signals.

[132] On 27 December 2018 the BeiDou Navigation Satellite System started to provide global services with a reported timing accuracy of 20 ns.

A project to observe twelve atomic clocks from 11 November 1999 to October 2014 resulted in a further demonstration that Einstein's theory of general relativity is accurate at small scales.

[143] In 2021 a team of scientists at JILA measured the difference in the passage of time due to gravitational redshift between two layers of atoms separated by one millimeter using a strontium optical clock cooled to 100 nanokelvins with a precision of 7.6×10−21 seconds.

[147][148] Accurate timekeeping is needed to prevent illegal trading ahead of time, in addition to ensuring fairness to traders on the other side of the globe.