Wave shoaling

It is caused by the fact that the group velocity, which is also the wave-energy transport velocity, decreases with water depth.

Under stationary conditions, a decrease in transport speed must be compensated by an increase in energy density in order to maintain a constant energy flux.

[2] Shoaling waves will also exhibit a reduction in wavelength while the frequency remains constant.

In other words, as the waves approach the shore and the water gets shallower, the waves get taller, slow down, and get closer together.

In shallow water and parallel depth contours, non-breaking waves will increase in wave height as the wave packet enters shallower water.

[3] This is particularly evident for tsunamis as they wax in height when approaching a coastline, with devastating results.

In the absence of the other effects, wave shoaling is the change of wave height that occurs solely due to changes in mean water depth – without alterations in wave propagation direction or energy dissipation.

Pure wave shoaling occurs for long-crested waves propagating perpendicular to the parallel depth contour lines of a mildly sloping sea-bed.

the wave height in deep water.

depends on the local water depth

Deep water means that the waves are (hardly) affected by the sea bed, which occurs when the depth

is larger than about half the deep-water wavelength

Under stationary conditions the total energy transport must be constant along the wave ray – as first shown by William Burnside in 1915.

[6] For waves affected by refraction and shoaling (i.e. within the geometric optics approximation), the rate of change of the wave energy transport is:[5] where

is the energy flux per unit crest length.

This can be formulated as a shoaling coefficient relative to the wave height in deep water.

[5][4] For shallow water, when the wavelength is much larger than the water depth – in case of a constant ray distance

(i.e. perpendicular wave incidence on a coast with parallel depth contours) – wave shoaling satisfies Green's law: with

Following Phillips (1977) and Mei (1989),[7][8] denote the phase of a wave ray as The local wave number vector is the gradient of the phase function, and the angular frequency is proportional to its local rate of change, Simplifying to one dimension and cross-differentiating it is now easily seen that the above definitions indicate simply that the rate of change of wavenumber is balanced by the convergence of the frequency along a ray; Assuming stationary conditions (

As waves enter shallower waters, the decrease in group velocity caused by the reduction in water depth leads to a reduction in wave length

because the nondispersive shallow water limit of the dispersion relation for the wave phase speed, dictates that i.e., a steady increase in k (decrease in

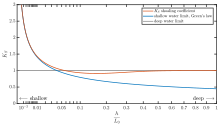

Quantities have been made dimensionless using the gravitational acceleration g and period T , with the deep-water wavelength given by L 0 = gT 2 /(2π) and the deep-water phase speed c 0 = L 0 / T . The grey line corresponds with the shallow-water limit c p = c g = √( gh ).

The phase speed – and thus also the wavelength L = c p T – decreases monotonically with decreasing depth. However, the group velocity first increases by 20% with respect to its deep-water value (of c g = 1 / 2 c 0 = gT /(4π)) before decreasing in shallower depths. [ 1 ]