Queen Victoria

Victoria, a constitutional monarch, attempted privately to influence government policy and ministerial appointments; publicly, she became a national icon who was identified with strict standards of personal morality.

[8] The system prevented the princess from meeting people whom her mother and Conroy deemed undesirable (including most of her father's family), and was designed to render her weak and dependent upon them.

[10] Victoria shared a bedroom with her mother every night, studied with private tutors to a regular timetable, and spent her play-hours with her dolls and her King Charles Spaniel, Dash.

[22]By 1836, Victoria's maternal uncle Leopold, who had been King of the Belgians since 1831, hoped to marry her to Prince Albert,[23] the son of his brother Ernest I, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha.

After the visit she wrote, "[Albert] is extremely handsome; his hair is about the same colour as mine; his eyes are large and blue, and he has a beautiful nose and a very sweet mouth with fine teeth; but the charm of his countenance is his expression, which is most delightful.

[28] Victoria wrote to King Leopold, whom she considered her "best and kindest adviser",[29] to thank him "for the prospect of great happiness you have contributed to give me, in the person of dear Albert ...

[37] She became the first sovereign to take up residence at Buckingham Palace[38] and inherited the revenues of the duchies of Lancaster and Cornwall as well as being granted a civil list allowance of £385,000 per year.

[39] At the start of her reign Victoria was popular,[40] but her reputation suffered in an 1839 court intrigue when one of her mother's ladies-in-waiting, Lady Flora Hastings, developed an abdominal growth that was widely rumoured to be an out-of-wedlock pregnancy by Sir John Conroy.

[45] Conroy, the Hastings family, and the opposition Tories organised a press campaign implicating the Queen in the spreading of false rumours about Lady Flora.

The assailant escaped; the following day, Victoria drove the same route, though faster and with a greater escort, in a deliberate attempt to bait Francis into taking a second aim and catch him in the act.

On 3 July, two days after Francis's death sentence was commuted to transportation for life, John William Bean also tried to fire a pistol at the queen, but it was loaded only with paper and tobacco and had too little charge.

[71] In a similar attack in 1849, unemployed Irishman William Hamilton fired a powder-filled pistol at Victoria's carriage as it passed along Constitution Hill, London.

[88] At the height of a revolutionary scare in the United Kingdom in April 1848, Victoria and her family left London for the greater safety of Osborne House,[89] a private estate on the Isle of Wight that they had purchased in 1845 and redeveloped.

[95] The following year, President Bonaparte was declared Emperor Napoleon III, by which time Russell's administration had been replaced by a short-lived minority government led by Lord Derby.

[101] They visited the Exposition Universelle (a successor to Albert's 1851 brainchild the Great Exhibition) and Napoleon I's tomb at Les Invalides (to which his remains had only been returned in 1840), and were guests of honour at a 1,200-guest ball at the Palace of Versailles.

[109] The queen felt "sick at heart" to see her daughter leave England for Germany; "It really makes me shudder", she wrote to Princess Victoria in one of her frequent letters, "when I look round to all your sweet, happy, unconscious sisters, and think I must give them up too – one by one.

In March 1864, a protester stuck a notice on the railings of Buckingham Palace that announced "these commanding premises to be let or sold in consequence of the late occupant's declining business".

[129] The following year she supported the passing of the Reform Act 1867 which doubled the electorate by extending the franchise to many urban working men,[130] though she was not in favour of votes for women.

[133] Disraeli's ministry only lasted a matter of months, and at the end of the year his Liberal rival, William Ewart Gladstone, was appointed prime minister.

[137] In late November 1871, at the height of the republican movement, the Prince of Wales contracted typhoid fever, the disease that was believed to have killed his father, and Victoria was fearful her son would die.

[140] Mother and son attended a public parade through London and a grand service of thanksgiving in St Paul's Cathedral on 27 February 1872, and republican feeling subsided.

[154] Between April 1877 and February 1878, she threatened five times to abdicate while pressuring Disraeli to act against Russia during the Russo-Turkish War, but her threats had no impact on the events or their conclusion with the Congress of Berlin.

"[156] Victoria saw the expansion of the British Empire as civilising and benign, protecting native peoples from more aggressive powers or cruel rulers: "It is not in our custom to annexe countries", she said, "unless we are obliged & forced to do so.

[166] Ponsonby and Randall Davidson, Dean of Windsor, who had both seen early drafts, advised Victoria against publication, on the grounds that it would stoke the rumours of a love affair.

[168] In early 1884, Victoria did publish More Leaves from a Journal of a Life in the Highlands, a sequel to her earlier book, which she dedicated to her "devoted personal attendant and faithful friend John Brown".

The Queen requested that any special celebrations be delayed until 1897, to coincide with her Diamond Jubilee,[191] which was made a festival of the British Empire at the suggestion of the Colonial Secretary, Joseph Chamberlain.

[193] One reason for including the prime ministers of the Dominions and excluding foreign heads of state was to avoid having to invite Victoria's grandson Wilhelm II, who, it was feared, might cause trouble at the event.

The procession paused for an open-air service of thanksgiving held outside St Paul's Cathedral, throughout which Victoria sat in her open carriage, to avoid her having to climb the steps to enter the building.

[217] Part of Victoria's extensive correspondence has been published in volumes edited by A. C. Benson, Hector Bolitho, George Earle Buckle, Lord Esher, Roger Fulford, and Richard Hough among others.

Royal haemophiliacs descended from Victoria included her great-grandsons, Alexei Nikolaevich, Tsarevich of Russia; Alfonso, Prince of Asturias; and Infante Gonzalo of Spain.

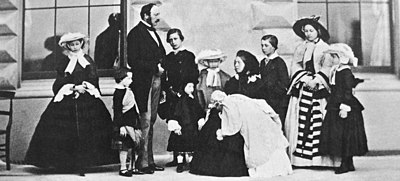

Left to right: Prince Alfred and the Prince of Wales ; the Queen and Prince Albert ; Princesses Alice , Helena and Victoria