Weight

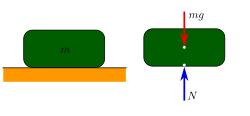

[1][2][3] Some standard textbooks[4] define weight as a vector quantity, the gravitational force acting on the object.

Yet others[7] define it as the magnitude of the reaction force exerted on a body by mechanisms that counteract the effects of gravity: the weight is the quantity that is measured by, for example, a spring scale.

[8] Further complications in elucidating the various concepts of weight have to do with the theory of relativity according to which gravity is modeled as a consequence of the curvature of spacetime.

In the teaching community, a considerable debate has existed for over half a century on how to define weight for their students.

[2] Discussion of the concepts of heaviness (weight) and lightness (levity) date back to the ancient Greek philosophers.

To Aristotle, weight and levity represented the tendency to restore the natural order of the basic elements: air, earth, fire and water.

Archimedes saw weight as a quality opposed to buoyancy, with the conflict between the two determining if an object sinks or floats.

As medieval scholars discovered that in practice the speed of a falling object increased with time, this prompted a change to the concept of weight to maintain this cause-effect relationship.

[2] The rise of the Copernican view of the world led to the resurgence of the Platonic idea that like objects attract but in the context of heavenly bodies.

Ultimately, he concluded weight was proportionate to the amount of matter of an object, not the speed of motion as supposed by the Aristotelean view of physics.

[clarification needed] Newton also recognized that weight as measured by the action of weighing was affected by environmental factors such as buoyancy.

The ambiguities introduced by relativity led, starting in the 1960s, to considerable debate in the teaching community as how to define weight for their students, choosing between a nominal definition of weight as the force due to gravity or an operational definition defined by the act of weighing.

Also it is equal to the force exerted by the body on its support because action and reaction have same numerical value and opposite direction.

This can make a considerable difference, depending on the details; for example, an object in free fall exerts little if any force on its support, a situation that is commonly referred to as weightlessness.

The operational definition, as usually given, does not explicitly exclude the effects of buoyancy, which reduces the measured weight of an object when it is immersed in a fluid such as air or water.

In many real world situations the act of weighing may produce a result that differs from the ideal value provided by the definition used.

The distinction between mass and weight is unimportant for many practical purposes because the strength of gravity does not vary too much on the surface of the Earth.

The poundal is defined as the force necessary to accelerate an object of one-pound mass at 1 ft/s2, and is equivalent to about 1/32.2 of a pound-force.

The sensation of weight is caused by the force exerted by fluids in the vestibular system, a three-dimensional set of tubes in the inner ear.

[dubious – discuss] It is actually the sensation of g-force, regardless of whether this is due to being stationary in the presence of gravity, or, if the person is in motion, the result of any other forces acting on the body such as in the case of acceleration or deceleration of a lift, or centrifugal forces when turning sharply.

When the scale is moved to another location on Earth, the force of gravity will be different, causing a slight error.

Since any variations in gravity will act equally on the unknown and the known weights, a lever-balance will indicate the same value at any location on Earth.

In the absence of a gravitational field, away from planetary bodies (e.g. space), a lever-balance would not work, but on the Moon, for example, it would give the same reading as on Earth.

The table below shows comparative gravitational accelerations at the surface of the Sun, the Earth's moon, each of the planets in the solar system.

The "surface" is taken to mean the cloud tops of the giant planets (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune).