Moment (physics)

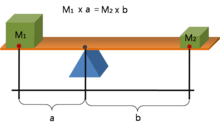

A moment is a mathematical expression involving the product of a distance and a physical quantity such as a force or electric charge.

Commonly used quantities include forces, masses, and electric charge distributions; a list of examples is provided later.

More complex forms take into account the angular relationships between the distance and the physical quantity, but the above equations capture the essential feature of a moment, namely the existence of an underlying

For these potentials, the expression can be used to approximate the strength of a field produced by a localized distribution of charges (or mass) by calculating the first few moments.

For sufficiently large r, a reasonable approximation can be obtained from just the monopole and dipole moments.

Measurements pertaining to multipole moments may be taken and used to infer properties of the underlying distribution.

This technique applies to small objects such as molecules,[2][3] but has also been applied to the universe itself,[4] being for example the technique employed by the WMAP and Planck experiments to analyze the cosmic microwave background radiation.

In works believed to stem from Ancient Greece, the concept of a moment is alluded to by the word ῥοπή (rhopḗ, lit.

[8] In particular, in extant works attributed to Archimedes, the moment is pointed out in phrasings like: Moreover, in extant texts such as The Method of Mechanical Theorems, moments are used to infer the center of gravity, area, and volume of geometric figures.

[6] Around 1450, Jacobus Cremonensis translates ῥοπή in similar texts into the Latin term momentum (lit.

[11][6]: 331 The same term is kept in a 1501 translation by Giorgio Valla, and subsequently by Francesco Maurolico, Federico Commandino, Guidobaldo del Monte, Adriaan van Roomen, Florence Rivault, Francesco Buonamici, Marin Mersenne[5], and Galileo Galilei.

One clue, according to Treccani, is that momento in Medieval Italy, the place the early translators lived, in a transferred sense meant both a "moment of time" and a "moment of weight" (a small amount of weight that turns the scale).

[b] In 1554, Francesco Maurolico clarifies the Latin term momentum in the work Prologi sive sermones.

In addition to body, weight, and moment, there is a certain fourth power, which can be called impetus or force.

[e] Aristotle investigates it in On Mechanical Questions, and it is completely different from [the] three aforesaid [powers or magnitudes].

[...]" in 1586, Simon Stevin uses the Dutch term staltwicht ("parked weight") for momentum in De Beghinselen Der Weeghconst.

In 1632, Galileo Galilei publishes Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems and uses the Italian momento with many meanings, including the one of his predecessors.

Salusbury translates Latin momentum and Italian momento into the English term moment.

[13] Huygens 1673 work involving finding the center of oscillation had been stimulated by Marin Mersenne, who suggested it to him in 1646.

[14][15] In 1811, the French term moment d'une force (English: moment of a force) with respect to a point and plane is used by Siméon Denis Poisson in Traité de mécanique.

In 1884, the term torque is suggested by James Thomson in the context of measuring rotational forces of machines (with propellers and rotors).

[19] Pearson wrote in response to John Venn, who, some years earlier, observed a peculiar pattern involving meteorological data and asked for an explanation of its cause.

The analogy between the mechanical concept of a moment and the statistical function involving the sum of the nth powers of deviations was noticed by several earlier, including Laplace, Kramp, Gauss, Encke, Czuber, Quetelet, and De Forest.