Welding

Welding is a fabrication process that joins materials, usually metals or thermoplastics, primarily by using high temperature to melt the parts together and allow them to cool, causing fusion.

Welding is a hazardous undertaking and precautions are required to avoid burns, electric shock, vision damage, inhalation of poisonous gases and fumes, and exposure to intense ultraviolet radiation.

Welding technology advanced quickly during the early 20th century, as world wars drove the demand for reliable and inexpensive joining methods.

The modern word was probably derived from the past-tense participle welled (wællende), with the addition of d for this purpose being common in the Germanic languages of the Angles and Saxons.

In the 1590 version this was changed to "...thei shullen welle togidere her swerdes in-to scharris..." (they shall weld together their swords into plowshares), suggesting this particular use of the word probably became popular in English sometime between these periods.

The ancient Greek historian Herodotus states in The Histories of the 5th century BC that Glaucus of Chios "was the man who single-handedly invented iron welding".

[7] The Middle Ages brought advances in forge welding, in which blacksmiths pounded heated metal repeatedly until bonding occurred.

The advances in arc welding continued with the invention of metal electrodes in the late 1800s by a Russian, Nikolai Slavyanov (1888), and an American, C. L. Coffin (1890).

[17] Resistance welding was also developed during the final decades of the 19th century, with the first patents going to Elihu Thomson in 1885, who produced further advances over the next 15 years.

[19] Flux covering the electrode primarily shields the base material from impurities, but also stabilizes the arc and can add alloying components to the weld metal.

Shielding gas became a subject receiving much attention, as scientists attempted to protect welds from the effects of oxygen and nitrogen in the atmosphere.

Porosity and brittleness were the primary problems, and the solutions that developed included the use of hydrogen, argon, and helium as welding atmospheres.

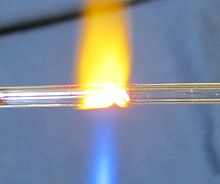

[19] The equipment is relatively inexpensive and simple, generally employing the combustion of acetylene in oxygen to produce a welding flame temperature of about 3100 °C (5600 °F).

[39] The process is versatile and can be performed with relatively inexpensive equipment, making it well suited to shop jobs and field work.

[41] A related process, flux-cored arc welding (FCAW), uses similar equipment but uses wire consisting of a steel electrode surrounding a powder fill material.

It can be applied to all of the same materials as GTAW except magnesium, and automated welding of stainless steel is one important application of the process.

This is important because in manual welding, it can be difficult to hold the electrode perfectly steady, and as a result, the arc length and thus voltage tend to fluctuate.

In these processes, arc length is kept constant, since any fluctuation in the distance between the wire and the base material is quickly rectified by a large change in current.

[51] In general, resistance welding methods are efficient and cause little pollution, but their applications are somewhat limited and the equipment cost can be high.

The advantages of the method include efficient energy use, limited workpiece deformation, high production rates, easy automation, and no required filler materials.

[55] The equipment and methods involved are similar to that of resistance welding, but instead of electric current, vibration provides energy input.

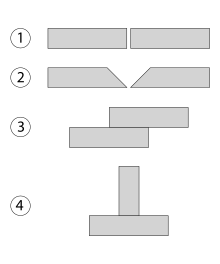

Other variations exist as well—for example, double-V preparation joints are characterized by the two pieces of material each tapering to a single center point at one-half their height.

Processes like laser beam welding give a highly concentrated, limited amount of heat, resulting in a small HAZ.

The only exception is material that is made from glass which is a combination of a supercooled liquid and polymers which are aggregates of large organic molecules.

[67] Ductility is an important factor in ensuring the integrity of structures by enabling them to sustain local stress concentrations without fracture.

[69] Since many common welding procedures involve an open electric arc or flame, the risk of burns and fire is significant; this is why it is classified as a hot work process.

These curtains, made of a polyvinyl chloride plastic film, shield people outside the welding area from the UV light of the electric arc, but cannot replace the filter glass used in helmets.

[75] Exposure to manganese welding fumes, for example, even at low levels (<0.2 mg/m3), may lead to neurological problems or to damage to the lungs, liver, kidneys, or central nervous system.

Furthermore, progress is desired in making more specialized methods like laser beam welding practical for more applications, such as in the aerospace and automotive industries.

On the other hand, quartz glass (fused silica) must be heated to over 3,000 °F (1,650 °C), but quickly loses its viscosity and formability if overheated, so an oxyhydrogen torch must be used.

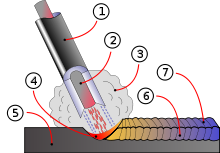

- Torch tip

- Filler rod

- Flame (outer envelope)

- Fusion

- Base metal

- Weld metal

- Flux coating

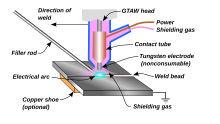

- Core wire

- Shield gas

- Fusion

- Base metal

- Weld metal

- Solidified slag

- Travel

- Contact tube

- Electrode

- Shielding gas

- Fusion

- Weld metal

- Base metal

- Flux core

- Tubular electrode

- Shield Gas

- Fusion

- Base metal

- Weld metal

- Solidified slag

- Square butt joint

- V butt joint

- Lap joint

- T-joint