Western Front (World War I)

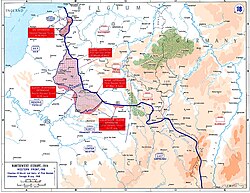

Following the outbreak of war in August 1914, the Imperial German Army opened the Western Front by invading Luxembourg and Belgium, then gaining military control of important industrial regions in France.

Entrenchments, machine gun emplacements, barbed wire, and artillery repeatedly inflicted severe casualties during attacks and counter-attacks and no significant advances were made.

[10][11] To break the deadlock of the trench warfare on the Western Front, both sides tried new military technology, including poison gas, aircraft, and tanks.

The German spring offensive of 1918 was made possible by the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk that ended the war of the Central Powers against Russia and Romania on the Eastern Front.

Using short, intense "hurricane" bombardments and infiltration tactics, the German armies moved nearly 100 kilometres (60 miles) to the west, the deepest advance by either side since 1914, but the success was short-lived.

[28] After the battle, Erich von Falkenhayn judged that it was no longer possible for Germany to win the war by purely military means and on 18 November 1914 he called for a diplomatic solution.

Hindenburg and Ludendorff continued to believe that Russia could be defeated by a series of battles which cumulatively would have a decisive effect, after which Germany could finish off France and Britain.

According to two prominent historians: Between the coast and the Vosges was a westward bulge in the trench line, named the Noyon salient after the French town at the maximum point of the German advance near Compiègne.

[32] On 10 March, as part of the larger offensive in the Artois region, the British Army fought the Battle of Neuve Chapelle to capture Aubers Ridge.

This advance was quickly ushered into service, in the Fokker E.I (Eindecker, or monoplane, Mark 1), the first single seat fighter aircraft to combine a reasonable maximum speed with an effective armament.

[49] However, the impact of German air superiority was diminished by their primarily defensive doctrine in which they tended to remain over their own lines, rather than fighting over entente held territory.

The main French assault was launched on 25 September and, at first, made good progress in spite of surviving wire entanglements and machine gun posts.

The British suffered heavy losses, especially due to machine gun fire during the attack and made only limited gains before they ran out of shells.

The town of Verdun was chosen for this because it was an important stronghold, surrounded by a ring of forts, that lay near the German lines and because it guarded the direct route to Paris.

The experienced French forces were successful in advancing but the British artillery cover had neither blasted away barbed wire, nor destroyed German trenches as effectively as was planned.

[68] The Verdun lesson learnt, the entente tactical aim became the achievement of air superiority and until September, German aircraft were swept from the skies over the Somme.

The attack made early progress, advancing 3,200–4,100 metres (3,500–4,500 yd) in places but the tanks had little effect due to their lack of numbers and mechanical unreliability.

[74] The Somme led directly to major new developments in infantry organisation and tactics; despite the terrible losses of 1 July, some divisions had managed to achieve their objectives with minimal casualties.

[80] The British continued offensive operations as the War Office claimed, with some justification, that this withdrawal resulted from the casualties the Germans received during the Battles of the Somme and Verdun, despite the entente suffering greater losses.

[84] During the winter of 1916–1917, German air tactics had been improved, a fighter training school was opened at Valenciennes and better aircraft with twin guns were introduced.

The 16 April attack, dubbed the Nivelle Offensive (also known as the Second Battle of the Aisne), would be 1.2 million men strong, preceded by a week-long artillery bombardment and accompanied by tanks.

Secrecy had been compromised and German aircraft gained air superiority, making reconnaissance difficult and in places, the creeping barrage moved too fast for the French troops.

[96] On 11 July 1917, during Unternehmen Strandfest (Operation Beachparty) at Nieuport on the coast, the Germans introduced a new weapon into the war when they fired a powerful blistering agent Sulfur mustard (Yellow Cross) gas.

[100] The battle has become a byword among some British revisionist historians for bloody and futile slaughter, whilst the Germans called Passchendaele "the greatest martyrdom of the war.

[103] The advance produced an awkward salient and a surprise German counter-offensive began on 30 November, which drove back the British in the south and failed in the north.

[105] The entente lacked unity of command and suffered from morale and manpower problems, the British and French armies were severely depleted and not in a position to attack in the first half of the year, while the majority of the newly arrived American troops were still training, with just six complete divisions in the line.

[106] Ludendorff decided on an offensive strategy beginning with a big attack against the British on the Somme, to separate them from the French and drive them back to the channel ports.

[119] The Hundred Days Offensive beginning in August proved the final straw and following this string of military defeats, German troops began to surrender in large numbers.

[121] The German Imperial Monarchy collapsed when General Groener, the successor to Ludendorff, backed the moderate Social Democratic Government under Friedrich Ebert, to forestall a revolution like those in Russia the previous year.

The unprecedented loss of life had a lasting effect on popular attitudes toward war, resulting later in an entente reluctance to pursue an aggressive policy toward Adolf Hitler.