William Sterling Parsons

William Sterling Parsons (26 November 1901 – 5 December 1953) was an American naval officer who worked as an ordnance expert on the Manhattan Project during World War II.

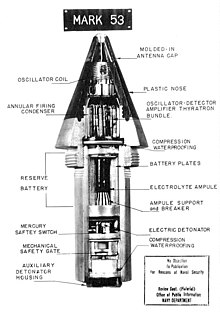

While the aircraft was en route to Hiroshima, Parsons climbed into the cramped and dark bomb bay, and inserted the powder charge and detonator.

A 1922 graduate of the United States Naval Academy, Parsons served on a variety of warships beginning with the battleship USS Idaho.

Parsons was on hand to watch the cruiser USS Helena shoot down the first enemy aircraft with a VT fuze in the Solomon Islands in January 1943.

Clara was the granddaughter of James Rood Doolittle, who served as US Senator from Wisconsin between 1857 and 1869, and of Joel Aldrich Matteson, Governor of Illinois from 1853 to 1857.

[3] In 1917 Parsons traveled to Roswell, New Mexico, to take the United States Naval Academy exam for one of the appointments by Senator Andrieus A. Jones.

As he was only 16, two years younger than most candidates, he was shorter and lighter than the physical standards called for, but managed to convince the examining board to admit him anyway.

[8] The ordnance course was normally followed by a relevant field posting, so Parsons was sent to the Naval Proving Ground in Dahlgren, Virginia, to further study ballistics under L. T. E.

[9] Following the usual pattern of alternating duty afloat and ashore, Parsons was posted to the battleship USS Texas in June 1930, with the rank of lieutenant.

On that occasion, Parsons left Martha with the newborn and three-year-old Peggy to care for and reported for duty the next day, believing that his first responsibility was to his ship.

In March 1938, Rear Admiral William R. Sexton had Parsons assigned to his flagship, the cruiser USS Detroit, as gunnery officer.

In June 1940, President Franklin D. Roosevelt approved the creation of the National Defense Research Committee (NDRC), under the direction of Vannevar Bush.

The radar set had to be made small enough to fit inside a shell, and its glass vacuum tubes had to first withstand the 20,000 g force of being fired from a gun, and then 500 rotations per second in flight.

[23] On 29 January 1942, Parsons reported to Blandy that a batch of fifty proximity fuzes from the pilot production plant had been test fired, and 26 of them had exploded correctly.

The research effort remained under Tuve but moved to the Johns Hopkins University's Applied Physics Laboratory (APL), where Parsons was BuOrd's representative.

The use of a version fired from howitzers against ground targets was authorized in response to the German Ardennes Offensive in December 1944, with deadly effect.

The creation of a practical weapon would necessarily require an expert in ordnance, and Oppenheimer tentatively penciled in Tolman for the role, but getting him released from OSRD was another matter.

[35] The next morning, Parsons received a phone call from Purnell, ordering him to report to Admiral King, who was now the commander in chief, US Fleet (Cominch).

[35] Parsons was relieved of his duties at Dahlgren and officially assigned to Admiral King's Cominch staff on 1 June 1943, with a promotion to the rank of captain.

[38] Parsons and his family moved into one of the houses on "Bathtub Row" that had formerly belonged to the headmaster and staff of the Los Alamos Ranch School.

Instead of the temporary two-story structure that Groves had envisioned in the interest of economy and not misusing the project's high priorities for labor and materials, Parsons had a well-built, modern, single-story school constructed.

Charles Critchfield, a mathematical physicist with ordnance experience at the Army's Aberdeen Proving Ground, was in charge of the Target, Projectile and Source Group.

Edward L. Bowles, the scientific adviser to the Secretary of War, Henry L. Stimson, was reluctant to part with Ramsey, but gave way under pressure from Groves, Tolman and Bush.

There was some aspect of service parochialism, and Parsons believed that involvement in the Manhattan Project would be important for the future of the Navy, but it was also due to the difficulty of getting highly skilled people from any source in wartime.

[52] Oppenheimer considered that there was a "reciprocal lack of confidence" between Parsons and Neddermeyer,[53] and in October 1943 he brought in George Kistiakowsky, who began a new attack on the implosion design.

Starting in November, the Army Air Forces Materiel Command at Wright Field, Ohio, began Silverplate, the codename for the modification of B-29s to carry the bombs.

En route, he stopped off in San Diego to visit his eighteen-year-old half-brother Bob, a US Marine who had been badly wounded in the Battle of Iwo Jima.

Parsons was joined by Purnell, who represented the Military Liaison Committee, and Brigadier General Thomas F. Farrell, Groves' Deputy for Operations.

[69] In November 1945, King created a new position of Deputy Chief of Naval Operations for Special Weapons, which was given to Vice Admiral Blandy.

On 4 December that year, Parsons heard of President Dwight Eisenhower's "blank wall" directive, blocking Oppenheimer from access to classified material.