William Turner (naturalist)

[4] He first published Libellus de Re herbaria in Latin in 1538, and later translated it into English because he believed herbalists were not sharing their knowledge.

He spent much of his leisure in the careful study of plants which he sought for in their native habitat, and described with an accuracy hitherto unknown in England.

Quite early in his career, Turner became interested in natural history and set out to produce reliable lists of English plants and animals, which he published as Libellus de re herbaria in 1538.

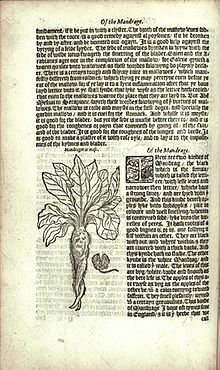

A new herball, wherin are conteyned the names of herbes… (London: imprinted by Steven Myerdman and soolde by John Gybken, 1551) is the first part of Turner's great work; the second was published in 1562 and the third in 1568, both by Arnold Birckman of Cologne.

These volumes gave the first clear, systematic survey of English plants, and with their admirable woodcuts (mainly copied from Leonhart Fuchs's 1542 De Historia Stirpium Commentarii Insignes) and detailed observations based on Turner's own field studies put the herbal on an altogether higher footing than in earlier works.

At the same time, however, Turner included an account of their "uses and vertues", and in his preface admits that some will accuse him of divulging to the general public what should have been reserved for a professional audience.

In 1562, Turner published the second part of his Herbal, dedicated to Sir Thomas Wentworth, son of the patron who had enabled him to go to Cambridge.

The second volume includes one of the earliest reference to the celebrated Glastonbury Thorn, only five miles from Wells, which Turner tells us "is grene all the wynter, as all they that dwell there about do stedfastly holde".

He claimed that the herbal described only English plant species "whereof is no mention made neither of ye old Grecianes nor Latines".

According to Tudor historian Lacey Baldwin Smith, for instance, "Religious discontent and civil rebellion were obviously walking hand in hand when William Turner dared speak out against [Henry VIII's] proclamation of 1543 limiting the reading of the Bible to men of social standing.

Historian of science Charles E. Raven wrote that "Turner, a shrewd observer and an excellent botanist, accepted transmutation as a commonplace event.