Wilson's disease

Wilson's disease (also called hepatolenticular degeneration) is a genetic disorder characterized by the excess build-up of copper in the body.

Liver-related symptoms include vomiting, weakness, fluid build-up in the abdomen, swelling of the legs, yellowish skin, and itchiness.

Brain-related symptoms include tremors, muscle stiffness, trouble in speaking, personality changes, anxiety, and psychosis.

[1] It was first described in 1854 by German pathologist Friedrich Theodor von Frerichs and is named after British neurologist Samuel Wilson.

Some are identified only because relatives have been diagnosed with Wilson's disease; many of these, when tested, turn out to have been experiencing symptoms of the condition but have not received a diagnosis.

[6] Liver disease may present itself as tiredness, jaundice, increased bleeding tendency or confusion (due to hepatic encephalopathy), and portal hypertension.

On examination, signs of chronic liver disease such as spider angiomata (small distended blood vessels, usually on the chest) may be observed.

Specific neurological symptoms usually then follow, often in the form of parkinsonism (cogwheel rigidity, bradykinesia, or slowed movements and a lack of balance are the most common parkinsonian features[8]) with or without a typical hand tremor, masked facial expressions, slurred speech, ataxia (lack of coordination), or dystonia (twisting and repetitive movements of part of the body).

[9] Cognition can also be affected in Wilson's disease, in two non-mutually exclusive categories: frontal lobe disorder (may present as impulsivity, impaired judgement, promiscuity, apathy, and executive dysfunction with poor planning and decision-making) and subcortical dementia (may present as slow thinking, memory loss, and executive dysfunction, without signs of aphasia, apraxia, or agnosia).

[8] Psychiatric problems due to Wilson's disease may include behavioral changes, depression, anxiety disorders, and psychosis.

[17] A normal variation in the PRNP gene can modify the course of the disease by delaying the age of onset and affecting the type of symptoms that develop.

This gene produces prion protein, which is active in the brain and other tissues and also appears to be involved in transporting copper.

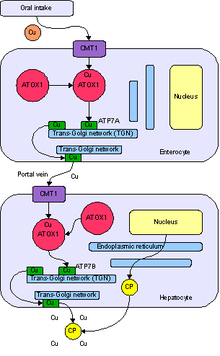

[16] When the amount of copper in the liver overwhelms the proteins that normally bind it, it causes oxidative damage to the liver through a process known as Fenton chemistry; this damage eventually leads to chronic active hepatitis, fibrosis (deposition of connective tissue), and cirrhosis.

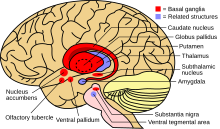

In the brain, most copper is deposited in the basal ganglia, particularly in the putamen and globus pallidus (together called the lenticular nucleus); these areas normally participate in the coordination of movement and play a significant role in neurocognitive processes such as the processing of stimuli and mood regulation.

[16] Why Wilson's disease causes hemolysis is unclear, but various lines of evidence suggest that a high level of free (nonceruloplasmin-bound) copper may be directly affecting the oxidation of hemoglobin, or inhibiting the energy-supplying enzymes in red blood cells, or causing direct damage to cell membranes.

[5][14] The combination of neurological symptoms, eye signs, and a low ceruloplasmin level is considered sufficient for the diagnosis of Wilson's disease.

Urine copper is elevated in Wilson's disease and is collected for 24 hours in a bottle with a copper-free liner.

[14] The eyes of the patient are examined using a slit lamp to look for Kayser–Fleischer rings, which are strongly associated with Wilson's disease and are caused by copper deposition on the inner cornea in Descemet's membrane.

Occasionally, lower levels of copper are found; in that case, the combination of the biopsy findings with all other tests could still lead to a formal diagnosis of Wilson's.

[5] In the earlier stages of the disease, the biopsy typically shows steatosis (deposition of fatty material), increased glycogen in the nucleus, and areas of necrosis (cell death).

In more advanced disease, the changes observed are quite similar to those seen in autoimmune hepatitis, such as infiltration by inflammatory cells, piecemeal necrosis, and fibrosis (scar tissue).

[5] Regional distributions of genes associated with Wilson's disease are important to follow, as this can help clinicians design appropriate screening strategies.

Zinc stimulates metallothionein, a protein in gut cells that binds copper and prevents its absorption and transport to the liver.

[14] In rare cases where none of the oral treatments is effective, especially with severe neurological disease, dimercaprol (British anti-Lewisite) is occasionally necessary.

[13] The disease bears the name of British physician Samuel Alexander Kinnier Wilson (1878–1937), a neurologist who described the condition, including the pathological changes in the brain and liver, in 1912.

[26] Wilson's work had been predated by, and drew on, reports from German neurologist Karl Westphal (in 1883), who termed it "pseudo-sclerosis"; by the British neurologist William Gowers (in 1888);[27] by the Finnish neuropathologist Ernst Alexander Homén (in 1889–1892), who noted the hereditary nature of the disease;[28] and by Adolph Strümpell (in 1898), who noted hepatic cirrhosis.

[30] In 1951, Cumings (in England), and New Zealand neurologist Derek Denny-Brown (working in the United States), simultaneously reported the first effective treatment, using the metal chelator British anti-Lewisite.

[27][33] The first oral chelation agent effective in Wilson's disease, penicillamine, was discovered in 1956 by British neurologist John Walshe.

[36] Zinc acetate therapy initially made its appearance in the Netherlands, where physicians Schouwink and Hoogenraad used it in 1961 and in the 1970s, respectively, and was further developed later by Brewer and colleagues at the University of Michigan.

[23][37] The genetic basis of Wilson's disease, and its link to ATP7B mutations, was elucidated by several research groups in the 1980s and 1990s.