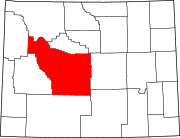

Wind River Indian Reservation

Archaeologists have found evidence that unique aspects of the Tukudika Mountain Shoshone or Sheepeater material culture such as soapstone bowls were in use in this region from the early 1800s going back 1,000 to 3,000 years or more.

These latter tribes came to the area due to geopolitical forces, as well as for food resources; trapper records after 1800 describe huge herds of tens of thousands of stampeding bison in the Wind River Basin, raising massive clouds of dust on the horizon.

(The Arapaho played a similar role of introducing the horse to the Great Plains, through trade between the Spanish settlements along the Rio Grande and the agricultural tribes along the Missouri River.)

Coming from the other direction, the post-1600s westward migration of Siouan and Algonquian-speaking peoples brought new populations onto the plains and traditional Shoshone territory of the middle Rocky Mountains.

Crow Chief Arapooish mentioned the Wind River Valley as a preferred wintering ground with salt bush and cottonwood bark for horse forage in a speech recorded in the 1830s and published in Washington Irving's Adventures of Captain Bonneville.

Washakie likely opted to challenge the Crow because the emigrant trails and increasing white settlement in Utah, Idaho, and Montana made hunting in those areas harder.

This left the Crow-occupied Wind River Valley as the only place Washakie could use force to secure hunting grounds from a rival tribe without significantly opposing American interests.

After prospectors discovered gold at South Pass in 1867, the United States Indian agent sought to limit numerous tribes from raiding mining camps by placing the Shoshone reservation in the Wind River Valley as a buffer.

The United States hoped that tribes like the Crow, Blackfeet, Cheyenne, Lakota, and Arapaho would attack their traditional Shoshone enemies instead of the miners.

The Arapaho briefly stayed in the Wind River valley in 1870, but left after miners and Shoshones attacked and killed tribal members and Black Bear, one of their leaders, as they moved lodges.

In 1904 the Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho ceded a portion of the reservation north of the Wind River to the United States and opened to white settlement.

In the winter of 1878–79, the United States Army escorted the Northern Arapaho to the Sweetwater Valley near Independence Rock and then temporarily placed them at the Shoshone's Fort Washakie Agency to receive rations.

In 1868–69, the Arapaho briefly sought to locate with the linguistically related Gros Ventres at the agency on the Milk River in Montana, but left after a smallpox epidemic.

Officers of the United States Army supported the idea of an Arapaho reservation in eastern Wyoming Territory — General Crook may have promised an agency on the Tongue River.

Yet federal policy prevented this from coming to fruition, partly because the United States had essentially stopped negotiating reservation treaties with tribes after 1868, preferring instead to use executive orders in such agreements.

Chief Black Coal had previously visited the Southern Arapaho reservation on the Canadian River in Oklahoma, finding the location unacceptable.

[17] The supposedly temporary placement of the Arapaho at Fort Washakie Agency became permanent because the United States government never took further action to relocate the tribe.

According to historian Loretta Fowler, Arapaho leaders at the time were aware they had no real legal status to reservation land in the Wind River Valley.

The license allows access to fishing lands on the southern half of the reservation, including in the tribal roadless area that encompasses part of the dramatic Wind River Range.

The spectacle is described on the Wind River Country's tourism website, telling prospective visitors, "If you close your eyes for a second the music will sweep you away.

[31] Yet the reservation community also suffers from the legacy of settler colonialism, dispossession from land, forced assimilation and cultural destruction, family disruption, environmental extraction and degradation, disenfranchisement, and inter-generational poverty.

[32] High Country News tribal desk editor Tristan Ahtone (Kiowa) used Wind River media coverage by the New York Times, CNN, and Business Insider as examples of simplistic negative narratives that future journalists can work to disrupt through accurate portrayals of Native American realities, both good and bad.

[34] In the early 21st century, the media reported problems of reservation poverty and unemployment, resulting in associated crime and a high rate of drug abuse.

According to this article, written by Timothy Williams, an Iraq war strategy, "the surge", was used to attempt to fight crime, taking hundreds of officers from the National Park Service and other federal agencies.

In 2013, Business Insider produced a photo scrapbook and indicated locals refer to different streets by infamously violent American locations such as Compton near Los Angeles.

The group created a disease management program based on the Chronic Care Model which focused on looking at members with or at risk of diabetes.

Due to the success of the program, a two-year grant from the AstraZeneca Foundation proposed to help 350 reservation residents who are at risk for cardiovascular disease.

"[44] According to Folo Akintan's preliminary data, a medical doctor and epidemiologist from the Rocky Mountain Tribal Epidemiology Center in Billings, Montana, four out of ten Wind River Reservation residents reported that they have had a relative die from cancer.

They reassured the residents that it was secure and wouldn't break; however, Wind River Environmental Quality Commission officials state that the pipe has broken multiple times within the past year.

[45] In 1993, the Northern Arapaho Tribe on the Wind River Reservation began a relationship with a high school in Centennial, Colorado, to "[promote] awareness to the co-existence of two very diverse cultures."