Aeolian processes

They are effective agents in regions with sparse vegetation, a lack of soil moisture and a large supply of unconsolidated sediments.

Although water is a much more powerful eroding force than wind, aeolian processes are important in arid environments such as deserts.

Much of North America and Europe are underlain by sand and loess of Pleistocene age originating from glacial outwash.

[14] Most aeolian deflation zones are composed of desert pavement, a sheet-like surface of rock fragments that remains after wind and water have removed the fine particles.

Polished or faceted surfaces called ventifacts are rare, requiring abundant sand, powerful winds, and a lack of vegetation for their formation.

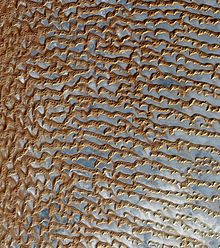

[20] Particles are transported by winds through suspension, saltation (skipping or bouncing) and creeping (rolling or sliding) along the ground.

[26][27] Most occur on the synoptic (regional) scale, due to strong winds along weather fronts,[28] or locally from downbursts from thunderstorms.

Here vegetation-stabilized sand dunes are found to the west and loess deposits to the east, further from the original sediment source in the Ogallala Formation at the feet of the Rocky Mountains.

[6] Some of the most significant experimental measurements on aeolian landforms were performed by Ralph Alger Bagnold,[39] a British army engineer who worked in Egypt prior to World War II.

[41] The discovery of dunes on Mars reinvigorated aeolian process research,[42] which increasingly makes use of computer simulation.

[6] For example, vast inactive ergs in much of the modern world attest to late Pleistocene trade wind belts being much expanded during the Last Glacial Maximum.

The abundant dust is attributed to a vigorous low-latitude wind system plus more exposed continental shelf due to low sea levels.

An example is the Selima Sand Sheet in the eastern Sahara Desert, which occupies 60,000 square kilometers (23,000 sq mi) in southern Egypt and northern Sudan.

[49] Aklé dunes are preserved in the geologic record as sandstone with large sets of cross-bedding and many reactivation surfaces.

They form over a prolonged period of time in areas of abundant sand and show a complex internal structure.

Those in Gran Desierto de Altar of Mexico are thought to have formed from precursor linear dunes due to a change in the wind pattern about 3000 years ago.

[6] These form on mud flats on the margins of saline bodies of water subject to strong prevailing winds during a dry season.

[54] Deserts cover 20 to 25 percent of the modern land surface of the earth, mostly between the latitudes of 10 to 30 degrees north or south.

The present relative abundance of sandy areas may reflect reworking of Tertiary sediments following the Last Glacial Maximum.

[56] Most modern deserts have experienced extreme Quaternary climate change, and the sediments that are now being churned by wind systems were generated in upland areas during previous pluvial (moist) periods and transported to depositional basins by stream flow.

Dune shapes determine whether sediment is deposited, simply moves across surface (a bypass system), or erosion takes place.

They are analogous to drainage maps, but are not as closely tied to topography, since wind can blow sand significant distances uphill.

All flowlines arise in the desert itself, and show indications of clockwise circulation roughly like high pressure cells.

The greatest deflation occurs in dried lake beds where trade winds form a low-level jet between the Tibesti Mountains and the Ennedi Plateau.

The flowlines eventually reach the, sea creating great plume of Saharan dust extending thousands of kilometers into the Atlantic Ocean.

It is estimated that 260 million tons of sediments are transported through this system each year, but the amount was much greater during the Last Glacial Maximum, based on deep-sea cores.

The Namib receives its sediments from the south through narrow deflation corridors from coast that cross more than 100 kilometers (62 mi) of bedrock to the erg.

It provides a record of glaciation, in the form of glacial loess layers separated by paleosols (fossil soils).

Successive migrating dunes deposited a vertical stacking of eolian beds between interdune bounding surfaces and regional supersurfaces.

Drilling core show dry and wet interdune surfaces and regional supersurfaces, and provide evidence of five or more cycles of erg expansion and contraction.