Yeast in winemaking

[1] The more sugars in the grapes, the higher the potential alcohol level of the wine if the yeast are allowed to carry out fermentation to dryness.

[3] The most common yeast associated with winemaking is Saccharomyces cerevisiae which has been favored due to its predictable and vigorous fermentation capabilities, tolerance of relatively high levels of alcohol and sulfur dioxide as well as its ability to thrive in normal wine pH between 2.8 and 4.

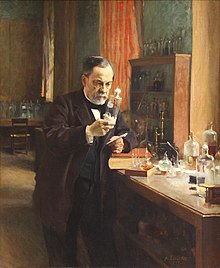

His work, which would later lead to Pasteur being considered one of the "Fathers of Microbiology", would uncover the connection between microscopic yeast cells and the process of the fermentation.

[8] Winemakers can now easily access yeast strains that accentuate desirable features in wine, such as aromatic compounds, mouthfeel, and fermentation kinetics.

This commercial availability of yeast strains has revolutionized the art of winemaking by allowing for more precise control over the fermentation process and the resultant wine's character.

This includes glycerol which is produced when an intermediate of the glycolysis cycle (dihydroxyacetone) is reduced to "recharge" the NADH enzyme needed to continue other metabolic activities.

[4] This is usually produced early in the fermentation process before the mechanisms to reduce acetaldehyde into ethanol to recharge NADH becomes the cell's primary means of maintaining redox balance.

[12] The process of leaving the wine to spend some contact with the lees has a long history in winemaking, being known to the Ancient Romans and described by Cato the Elder in the 2nd century BC.

Typically when wines are left in contact with their lees, they are regularly stirred in order to release the mannoproteins, polysaccharides and other compounds that were present in the yeast cell walls and membranes.

This stirring also helps avoid the development of reductive sulfur compounds like mercaptans and hydrogen sulfide that can appear if the lees layer is more than 10 cm (3.9 in) thick and undisturbed for more than a week.

[4] The production of Champagne and many sparkling wines requires a second fermentation to occur in the bottle in order to produce the carbonation necessary for the style.

A small amount of sugared liquid is added to individual bottles, and the yeast is allowed to convert this to more alcohol and carbon dioxide.

This sequencing helped confirm the nearly century of work by mycologists and enologists in identifying different strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae that are used in beer, bread and winemaking.

[3] Another less measurable difference that are subject to more debate and questions of winemakers preference is the influence of strain selection on the varietal flavors of certainly grape varieties such as Sauvignon blanc and Sémillon.

Other aromatic varieties such as Gewürztraminer, Riesling and Muscat may also be influenced by yeast strains containing high levels of glycosidases enzymes that can modify monoterpenes.

Similarly, though potentially to a much smaller extent, other varieties could be influenced by hydrolytic enzymes working on aliphatics, norisoprenoids, and benzene derivatives such as polyphenols in the must.

They are capable of starting a fermentation and often begin this process as early as the harvest bin when clusters of grapes get slightly crushed under their own weight.

Some winemakers will try to "knock out" these yeasts with doses of sulfur dioxide, most often at the crusher before the grapes are pressed or allowed to macerate with skin contact.

In wine regions such as Bordeaux, classified and highly regarded estates will often tout the quality of their resident "chateau" strains.

To this extent, wineries will often take the leftover pomace and lees from winemaking and return them to the vineyard to be used as compost in order to encourage the sustained presence of favorable strains.

Not only could this unpredictability include the presence of off-flavors/aromas and higher volatile acidity but also the potential for a stuck fermentation if the indigenous yeast strains are not vigorous enough to fully convert all the sugars.

While these non-Saccharomyces ferment glucose and fructose into alcohol, they also have the potential to create other intermediates that could influence the aroma and flavor profile of the wine.

These include not only an available energy source (carbon in the form of sugars such as glucose) and yeast assimilable nitrogen (ammonia and amino acids or YAN) but also minerals (such as magnesium) and vitamins (such as thiamin and riboflavin) that serve as important growth and survival factors.

[4] Saccharomyces cerevisiae can assimilate nitrogen from both inorganic (ammonia and ammonium) and organic forms (amino acids, particularly arginine).

However, this autolysis can also release sulfur-link compounds (such as the breakdown of amino acid cysteine) which can combine with other molecules and react with alcohol to create volatile thiols that can contribute to a "stinky fermentation" or later development into various wine faults.

[4] Cultured yeasts that are freeze-dried and available for inoculation of wine must are deliberately grown in commercial labs in high oxygen/low sugar conditions that favor the development of these survival factors.

These can include the presence of "off flavors" and aromas that can be the by-product of some "wild yeast" fermentation such as those by species within the genera of Kloeckera and Candida.

[4] In the presence of oxygen several species of Candida and Pichia can create a film surface on top of the wine in the tank of barrel.

Allowed to go unchecked, these yeasts can rapidly deplete the available free sulfur compounds that keeps a wine protected from oxidation and other microbial attack.

[5] Once Brett is in a winery, it is very difficult to control even with strict hygiene and the discarding of barrels and equipment that has previously come into contact with "Bretty" wine.