Witchcraft

The others define the witch figure as any person who uses magic ... or as the practitioner of nature-based Pagan religion; or as a symbol of independent female authority and resistance to male domination.

[19]According to the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial, Summary or Arbitrary Executions there is "difficulty of defining 'witches' and 'witchcraft' across cultures—terms that, quite apart from their connotations in popular culture, may include an array of traditional or faith healing practices".

[citation needed] Witches are commonly believed to cast curses; a spell or set of magical words and gestures intended to inflict supernatural harm.

[41] A common belief in cultures worldwide is that witches tend to use something from their target's body to work magic against them; for example hair, nail clippings, clothing, or bodily waste.

[22] Another widespread belief among Indigenous peoples in Africa and North America is that witches cause harm by introducing cursed magical objects into their victim's body; such as small bones or ashes.

[57] Some of the more hostile churchmen and secular authorities tried to smear folk-healers and magic-workers by falsely branding them 'witches' and associating them with harmful 'witchcraft',[54] but generally the masses did not accept this and continued to make use of their services.

[4] Emma Wilby says folk magicians in Europe were viewed ambivalently by communities, and were considered as capable of harming as of healing,[60] which could lead to their being accused as malevolent witches.

The Constitutio Criminalis Carolina (1532) of the Holy Roman Empire, and the Danish Witchcraft Act of 1617, stated that workers of folk magic should be dealt with differently from witches.

[89] In this early stage, witches were not necessarily considered evil, but took 'white' and 'black' forms, could help others using magic and medical knowledge, generally lived in rural areas and sometimes exhibited ecstatic behavior.

[89] In ancient Mesopotamia, a witch (m. kaššāpu, f. kaššāptu, from kašāpu ['to bewitch'][88]) was "usually regarded as an anti-social and illegitimate practitioner of destructive magic ... whose activities were motivated by malice and evil intent and who was opposed by the ašipu, an exorcist or incantation-priest".

[89] The stereotypical witch mentioned in the sources tended to be those of low status who were weak or otherwise marginalized, including women, foreigners, actors, and peddlers.

[87] The Law Code of Hammurabi (18th century BCE) allowed someone accused of witchcraft (harmful magic) to undergo trial by ordeal, by jumping into a holy river.

[93] The medieval Middle East experienced shifting perceptions of witchcraft under Islamic and Christian influences, sometimes revered for healing and other times condemned as heresy.

Among Catholics, Protestants, and the secular leadership of late medieval/early modern Europe, fears about witchcraft rose to fever pitch and sometimes led to large-scale witch-hunts.

[107] The historical continuity of witchcraft in the Middle East underlines the complex interaction between spiritual beliefs and societal norms across different cultures and epochs.

Today, some Wiccans and members of related traditions self-identify as "witches" and use the term "witchcraft" for their magico-religious beliefs and practices, primarily in Western anglophone countries.

It is often translated as "witchcraft" or "sorcery", but it has a broader meaning that encompasses supernatural harm, healing and shapeshifting; this highlights the problem of using European terms for African concepts.

[121] The Democratic Republic of the Congo witnessed a disturbing trend of child witchcraft accusations in Kinshasa, leading to abuse and exorcisms supervised by self-styled pastors.

[124] Malawi faces a similar issue of child witchcraft accusations, with traditional healers and some Christian counterparts involved in exorcisms, causing abandonment and abuse of children.

[133][134] Native American peoples such as the Cherokee,[135] Hopi,[136] the Navajo[5] among others,[137] believed in malevolent "witch" figures who could harm their communities by supernatural means; this was often punished harshly, including by execution.

Anthropologist Ruth Behar writes that Mexican Inquisition cases "hint at a fascinating conjecture of sexuality, witchcraft, and religion, in which Spanish, indigenous, and African cultures converged".

[144] Belief in witchcraft is a constant in the history of colonial Brazil, for example the several denunciations and confessions given to the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith of Bahia (1591–1593), Pernambuco and Paraíba (1593–1595).

[149] In ancient Mesopotamia (Sumeria, Assyria, Babylonia), a witch (m. kaššāpu, f. kaššāptu) was "usually regarded as an anti-social and illegitimate practitioner of destructive magic ... motivated by malice and evil intent".

[150] As the ancient Hebrews focused on their worship on Yahweh, Judaism clearly distinguished between forms of magic and mystical practices which were accepted, and those which were viewed as forbidden or heretical, and thus "witchcraft".

[citation needed] European belief in witchcraft can be traced back to classical antiquity, when concepts of magic and religion were closely related.

[152] According to Pliny, the 5th century BCE laws of the Twelve Tables laid down penalties for uttering harmful incantations and for stealing the fruitfulness of someone else's crops by magic.

The blending of ecclesiastical and secular jurisdictions in Russia's approach to witchcraft trials highlighted the intertwined nature of religious and political power during that time.

As the 17th century progressed, the fear of witches shifted from mere superstition to a tool for political manipulation, with accusations used to target individuals who posed threats to the ruling elite.

Drawing inspiration from ceremonial magic, historical paganism, and the now-discredited witch-cult theory, Wicca emphasizes a connection to nature, the divine, and personal growth.

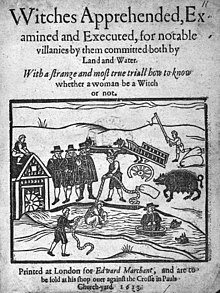

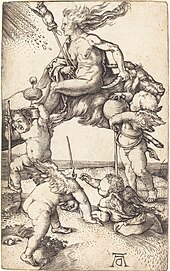

Many scholars attribute their manifestation in art as inspired by texts such as Canon Episcopi, a demonology-centered work of literature, and Malleus Maleficarum, a "witch-craze" manual published in 1487, by Heinrich Kramer and Jacob Sprenger.