Gender inequality in Bolivia

[15] Since the empowerment of women in government in Bolivia, more than 200 organizations that fall under the umbrella of the Coordinadora de la Mujer have been started.

It has small effects to the rural community because of the conception of the women's gender role as a wife to their husbands, how they participate in development work, and they don't take the opportunity to earn income.

An indigenous group, the Aymaras believe in the term Chachawarmi, which[16] means to have men and women be represented equally.

A study in 2009 focused mostly on Aymara activists living in the outskirts of La Paz analyzes in how they associate traditional customs, state politics and native activism.

The feminists convey the idea that Chachawarmi system undermines the Aymara women's participation because they do not engage much in the discussions or community meetings.

[16] Some of the Aymara community stated they do not want to trade in or be decolonized from their traditional customs if they agree to live in accordance to the political laws and policies.

There is no direct solution to this debate between gender politics and decolonization of the Aymaran people of Bolivia, but the analysis of understanding the different opinions of it is evaluated.

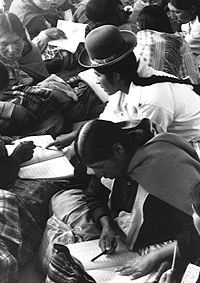

[18] Girls in rural areas generally attend school up until the 3rd grade due to the demand of household work and helping to take care of younger siblings.

However, for men it doesn't matter if they migrated to an urban city from a rural community, they will more likely have opportunities to participate in the labor force.

For women, the difference in making a certain amount of money in the labor market depends highly on their language skills.

According to scholar Lourdes Beneria, there needs to be a balance between the family and labor market by integrating the capabilities approach (Nussbaum) [23] and reconsider European policies.

[24] In Bolivia because there is not mobilization of domestic and market labor, women usually don't separate child care from work responsibilities.

Using a scholar, Ingrid Robeyns list is not completely universal, but function with a particular group of people who have different types of work than others.

(1) being able to raise children and to take care of other; (2) being able to work in the labor market or to undertake other projects; (3) being able to be mobile; (4) being able to engage in leisure activities; and (5) being able to exercise autonomy in allocating one's time.

[14] In 2009, the Vice-Ministry for Equal Opportunities was created within the Ministry of Justice to promote women's rights by making public policies within the whole country.

Bono Juana Azurday (BJA)[26] is a conditional cash transfer scheme,[26] which assists people living in poverty by giving them monthly payments.

[26] The women were required to go to education classes, participate in maternal health activities and go to family planning sessions.

The CCT program did not pay much attention to the women's voice, give them more opportunities in order to move forward in the economy or could help them participate more as a community.

A 1986 report from a hospital in La Paz stated that out of the 1,432 cases of rape and abuse, 66 percent were committed against women.

Since 1973, domestic abuse has been cited as a reason for separation or divorce, but was not allowed to be taken to court by family members, except in cases when the injuries caused incapacitation for more than 30 days.

[27] Poor indigenous women are prone to often working in menial low paying jobs such as domestic service.

Maids also may experience discrimination, not being allowed to enter certain rooms of houses and utilize their employers utensils and household items.

In 2013, Bolivia passed a new comprehensive domestic violence law, which outlaws many forms of abuse of women, including marital rape.

[29] Between 1992 and 1993, child mortality rate went down for children 5 years and under, due to a primary healthcare programme in a rural community of Bolivia.

In addition, the availability of clean water and sanitation was located within intervention areas, but only reached 10 percent of households.

[9] Indigenous couples are also less prone to discussing family planning with each other, despite male partner desires to not want additional children, as well.

Indigenous women feel that their partners don't want to discuss the topic of family planning, thus the conversation is never had.

Despite this communication problem, the Guttmacher Institute report found that the majority of both indigenous and non-indigenous couples approve of family planning.

[19] A 1998 survey reported that maternal death in Bolivia was one of the highest in the world, with women living in the altiplano suffering from higher rates.

Mothers often work at market, or as cooks, domestic servants or similar service jobs in order to provide for the family.