Women in early modern Scotland

In higher social ranks, marriages were often political in nature and the subject of complex negotiations in which women as matchmakers or mothers could play a major part.

[4][5] In noble society, widowhood created some very wealthy and powerful women, including Catherine Campbell, who became the richest widow in the kingdom when her husband, the ninth earl of Crawford, died in 1558 and the twice-widowed Margaret Ker, dowager lady Yester, described in 1635 as having "the greatest conjunct fie [fiefdom] that any lady hes in Scotland".

Concerns over this threat to male authority were exemplified by John Knox's The First Blast of the Trumpet Against the Monstruous Regiment of Women (1558), which advocated the deposition of all reigning queens.

Most of the political nation took a pragmatic view of the situation, accepting Mary as queen, but the strains that this paradox created may have played a part in the later difficulties of the reign.

Scottish women in this period had something of a reputation among foreign observers for being forthright individuals, with the Spanish ambassador to the court of James IV noting that they were "absolute mistresses of their houses and even their husbands".

Some mothers took a leading role in negotiating marriages, as Lady Glenorchy did for her children in the 1560s and 1570s, or as matchmakers, finding suitable and compatible partners for others.

In the Highlands they may have been even more significant as there is evidence that many men considered agricultural work to be beneath their status and in places they may have formed the majority of the rural workforce.

[15] There is evidence of single women engaging in independent economic activity, particularly for widows, who can be found keeping schools, brewing ale and trading.

[16] Lower down the social scale the rolls of poor relief indicate that large numbers of widows with children endured a marginal existence and were particularly vulnerable in times of economic hardship.

[14] "Masterless women", who had no responsible fathers or husbands may have made up as much as 18 percent of all households and particularly worried authorities who gave instructions to take particular notice of them.

Initially these were aimed at the girls of noble households, but by the eighteenth century there were complaints that the daughters of traders and craftsmen were following their social superiors into these institutions.

[20] By the eighteenth century many poorer girls were being taught in dame schools, informally set up by a widow or spinster to teach reading, sewing and cooking.

[27] There are 50 autobiographies extant from the late seventeenth to the early eighteenth century, of which 16 were written by women, all of which are largely religious in content.

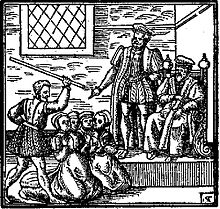

[29] The most prominent examples were the women who threw their cuttie-stools at the dean who was reading the new "English" service book in St. Giles Cathedral in 1637, precipitating the Bishop's Wars (1639–40), between the Presbyterian Covenanters and the king, who favoured an episcopalian structure in the church, similar to that in England.

[30] According to R. A. Houston, women probably had more freedom of expression and control over their spiritual destiny in groups outside the established church such the Quakers, who had a presence in the country from the mid-seventeenth century.

[14] Women were disciplined in kirk sessions and civil courts for stereotypical offenses including scolding and prostitution, which were seen as deviant, rather than criminal.

[39] The proliferation of partial explanations for the witch hunt has led some historians to proffer the concept of "associated circumstances", rather than one single significant cause.