World-systems theory

[3] World-systems theorists argue that their theory explains the rise and fall of states, income inequality, social unrest, and imperialism.

[7] Components of the world-systems analysis are longue durée by Fernand Braudel, "development of underdevelopment" by Andre Gunder Frank, and the single-society assumption.

[4][20] The Annales School tradition, represented most notably by Fernand Braudel, influenced Wallerstein to focus on long-term processes and geo-ecological regions as units of analysis.

[23] Other world-systems thinkers include Oliver Cox, Samir Amin, Giovanni Arrighi, and Andre Gunder Frank, with major contributions by Christopher Chase-Dunn, Beverly Silver, Janet Abu Lughod, Li Minqi, Kunibert Raffer, and others.

[24] During the Industrial Revolution, for example, English capitalists exploited slaves (unfree workers) in the cotton zones of the American South, a peripheral region within a semiperipheral country, United States.

In recognizing a tripartite pattern in the division of labor, world-systems analysis criticized dependency theory with its bimodal system of only cores and peripheries.

A world-empire (examples, the Roman Empire, Han China) are large bureaucratic structures with a single political center and an axial division of labor, but multiple cultures.

Cyclical rhythms represent the short-term fluctuation of economy, and secular trends mean deeper long run tendencies, such as general economic growth or decline.

[31] Some argue that this theory, though, ignores local efforts of innovation that have nothing to do with the global economy, such as the labor patterns implemented in Caribbean sugar plantations.

Since its creation, G-77 members have collaborated with two main aims: 1) decreasing their vulnerability based on the relative size of economic influence, and 2) improving outcomes for national development.

[34] In a health realm, studies have shown the effect of less industrialized countries’, the periphery's, acceptance of packaged foods and beverages that are loaded with sugars and preservatives.

This orthodox perspective, rooted in legal positivism, is challenged by the argument that global capitalism functions as a de facto sovereign power, shaping and enforcing international law in a hierarchical, top-down manner.

Scholars like Antony Anghie have examined the historical role of international law in advancing colonial agendas, aligning this analysis with the Marxian concept of primitive accumulation.

This concept situates colonialism within the broader framework of capital accumulation, demonstrating how IL has historically facilitated the exploitation and subordination of non-European states.

From this perspective, international law is not a neutral framework of horizontal equality but a tool that mirrors and perpetuates the dominance of global capital.

[43] Historically, cores were located in northwestern Europe (England, France, Netherlands) but later appeared in other parts of the world such as the United States, Canada, and Australia.

[10] Further, semi-peripheries act as buffers between cores and peripheries[10] and thus "...partially deflect the political pressures which groups primarily located in peripheral areas might otherwise direct against core-states" and stabilise the world system.

[10] Historically, two examples of semiperipheral states would be Spain and Portugal, which fell from their early core positions but still managed to retain influence in Latin America.

The interstate system arose either as a concomitant process or as a consequence of the development of the capitalist world-system over the course of the “long” 16th century as states began to recognize each other's sovereignty and form agreements and rules between themselves.

[46] Wallerstein wrote that there were no concrete rules about what exactly constitutes an individual state as various indicators of statehood (sovereignty, power, market control etc.)

[10] Wallerstein traces the origin of today's world-system to the "long 16th century" (a period that began with the discovery of the Americas by Western European sailors and ended with the English Revolution of 1640).

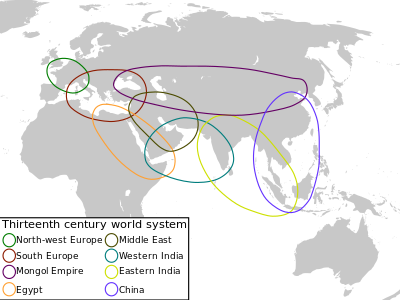

Janet Abu Lughod argues that a pre-modern world system extensive across Eurasia existed in the 13th century prior to the formation of the modern world-system identified by Wallerstein.

She contends that the Mongol Empire played an important role in stitching together the Chinese, Indian, Muslim and European regions in the 13th century, before the rise of the modern world system.

Andre Gunder Frank goes further and claims that a global world system that includes Asia, Europe and Africa has existed since the 4th millennium BCE.

[51] Andrey Korotayev goes even further than Frank and dates the beginning of the world system formation to the 10th millennium BCE and connects it with the start of the Neolithic Revolution in the Middle East.

[43][44][53] The first state to gain clear dominance was the Netherlands in the 17th century, after its revolution led to a new financial system that many historians consider revolutionary.

[10] By 1900, the modern world system appeared very different from that of a century earlier in that most of the periphery societies had already been colonised by one of the older core states.

[5] The semiperiphery was typically composed of independent states that had not achieved Western levels of influence, while poor former colonies of the West formed most of the periphery.

[4] William I. Robinson has criticized world-systems theory for its nation-state centrism, state-structuralist approach, and its inability to conceptualize the rise of globalization.

[54] Robinson suggests that world-systems theory does not account for emerging transnational social forces and the relationships forged between them and global institutions serving their interests.