Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period

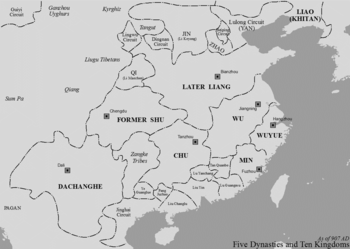

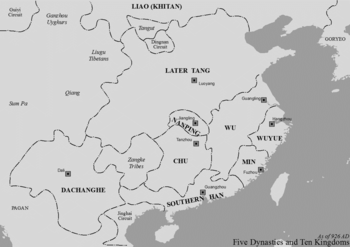

The Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period (Chinese: 五代十國) was an era of political upheaval and division in Imperial China from 907 to 979.

Many states had been de facto independent long before 907 as the late Tang dynasty's control over its numerous fanzhen officials waned, but the key event was their recognition as sovereign by foreign powers.

Towards the end of the Tang dynasty, the imperial government granted increased powers to the jiedushi (Chinese: 節度使), the regional military governors.

The An Lushan (755–763) and Huang Chao rebellions weakened the imperial government, and by the early 10th century the jiedushi commanded de facto independence from its authority.

In the last decades of the Tang dynasty, they were not even appointed by the central court anymore, but developed hereditary systems, from father to son or from patron to protégé.

[2] Due to the decline of Tang central authority after the An Lushan Rebellion, there was a growing tendency to superimpose large regional administrations over the old districts and prefectures that had been used since the Qin dynasty (221–206 BC).

The first stage (880–910) consists of the period between the Huang Chao Rebellion and the formal end of the Tang dynasty, which saw chaotic fighting between warlords who controlled approximately one or two prefectures each.

Southern China, divided into several independent dynastic kingdoms, was more stable than the North which saw constant regime change.

Consequently, the Southern kingdoms were able to embark on trade, land reclamation, and infrastructure projects, laying the groundwork for the Song Dynasty economic boom.

[4] According to Nicholas Tackett, the three provinces of Hebei (Chengde, Youzhou, Weibo) were able to maintain much greater autonomy from the central government in the aftermath of the An Lushan rebellion.

With their administration under local military control, these provinces never submitted tax revenues, and governorships lapsed into hereditary succession.

These families had risen to prominence due to the unraveling of central authority after the An Lushan Rebellion, despite lacking esteemed ancestry.

Zhao, also a professional soldier, rose through the ranks of the Later Zhou before seizing the throne in the Chenqiao Mutiny in 960, which ended the era of the Five Dynasties.

[12] The Southern kingdoms were founded by men of low social status who rose up through superior military ability, who were later scorned as "bandits" by future scholars.

However, once established, these rulers took great pains to portray themselves as promoters of culture and economic development so as to legitimize their rule; many wooed former Tang courtiers to help administer their states.

Within a few years, he had consolidated his power by destroying neighbours and forcing the move of the imperial capital to Luoyang, which was within his region of influence.

In the final years of the Tang dynasty, rival warlords declared independence in the provinces they governed—not all of which recognized the emperor's authority.

Li Keyong was the jiedushi for the Hedong circuit in present Shanxi, forming a polity called Jin (晉).

He defeated Liu Shouguang (who had proclaimed a Yan Empire in 911) in 915, and declared himself emperor in 923; within a few months, he brought down the Later Liang regime.

In return for their aid, Shi Jingtang promised annual tribute and the Sixteen Prefectures (modern northern Hebei and Beijing) to the Khitans.

To fill the power vacuum, the jiedushi Liu Zhiyuan entered the imperial capital in 947 and proclaimed the advent of the Later Han, establishing a third successive Shatuo reign.

After the death of Guo Wei in 954, his adopted son Chai Rong succeeded the throne and began a policy of expansion and reunification.

One month after Chai Rong took the throne, Liu Chong, Emperor of Northern Han, allied with Liao dynasty to launch an assault on Later Zhou.

Because the Later Tang was in decline and Li Cunxu was killed in a revolt, Meng Zhixiang found the opportunity to reassert Shu's independence.

Finally, Wuyue and Qingyuan Jiedushi gave up their land to Northern Song in 978, bringing all of southern China under the control of the central government.

The greater stability of the Ten Kingdoms, especially the longevity of Wuyue and Southern Han, would contribute to the development of distinct regional identities within China.

Written from the northern viewpoint, these chronicles organized the history around the Five Dynasties (the north), presenting the Ten Kingdoms (the south) as illegitimate, self-absorbed and indulgent.

[1] Several Northern dynasties originated in the northeast, and centralisation of the north led to a migration of provincial elites into the capital, particularly northeasterners, creating a new metropolitan culture.

This was distinct from the five Northern dynasties, who never supported extended monastic lineage networks but instead typically sought to restrict them and draw on their economic and military resources.

This view reflects both actual problems with the administration of justice and the bias of Confucian historians, who disapproved of the decentralization and militarization that characterized this period.