X-ray fluorescence

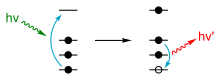

[2][3] When materials are exposed to short-wavelength X-rays or to gamma rays, ionization of their component atoms may take place.

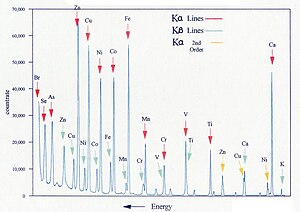

Figure 2 shows the typical form of the sharp fluorescent spectral lines obtained in the wavelength-dispersive method (see Moseley's law).

In order to excite the atoms, a source of radiation is required, with sufficient energy to expel tightly held inner electrons.

Conventional X-ray generators, based on electron bombardment of a heavy metal (i.e. tungsten or rhodium) target are most commonly used, because their output can readily be "tuned" for the application, and because higher power can be deployed relative to other techniques.

For portable XRF spectrometers, copper target is usually bombared with high energy electrons, that are produced either by impact laser or by pyroelectric crystals.

[4][5] Alternatively, gamma ray sources, based on radioactive isotopes (such as 109Cd, 57Co, 55Fe, 238Pu and 241Am) can be used without the need for an elaborate power supply, allowing for easier use in small, portable instruments.

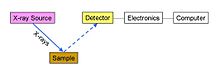

In energy-dispersive analysis, the fluorescent X-rays emitted by the material sample are directed into a solid-state detector which produces a "continuous" distribution of pulses, the voltages of which are proportional to the incoming photon energies.

In wavelength-dispersive analysis, the single-wavelength radiation produced by the monochromator is passed into a chamber containing a gas that is ionized by the X-ray photons.

A central electrode is charged at (typically) +1700 V with respect to the conducting chamber walls, and each photon triggers a pulse-like cascade of current across this field.

Because of this, for high-performance analysis, the path from tube to sample to detector is maintained under vacuum (around 10 Pa residual pressure).

The lithium-drifted centre part forms the non-conducting i-layer, where Li compensates the residual acceptors which would otherwise make the layer p-type.

To make the most efficient use of the detector, the tube current should be reduced to keep multi-photon events (before discrimination) at a reasonable level, e.g. 5–20%.

These elaborate correction processes tend to be based on empirical relationships that may change with time, so that continuous vigilance is required in order to obtain chemical data of adequate precision.

Field Portable XRF analysers currently on the market weigh less than 2 kg, and have limits of detection on the order of 2 parts per million of lead (Pb) in pure sand.

This is achieved in two different ways: In order to keep the geometry of the tube-sample-detector assembly constant, the sample is normally prepared as a flat disc, typically of diameter 20–50 mm.

This is achieved in two ways: A Söller collimator is a stack of parallel metal plates, spaced a few tenths of a millimeter apart.

In the case of fixed-angle monochromators (for use in simultaneous spectrometers), crystals bent to a logarithmic spiral shape give the best focusing performance.

These can in principle be custom-manufactured to diffract any desired long wavelength, and are used extensively for elements in the range Li to Mg.

-line spectra and the surrounding chemical environment of the ionized metal atom, measurements of the so-called valence-to-core (V2C) energy region become increasingly viable.

[9] This means, that by intense study of these spectral lines, one can obtain several crucial pieces of information from a sample.

In addition, they need sufficient energy resolution to allow filtering-out of background noise and spurious photons from the primary beam or from crystal fluorescence.

There are four common types of detector: Gas flow proportional counters are used mainly for detection of longer wavelengths.

The argon is ionised by incoming X-ray photons, and the electric field multiplies this charge into a measurable pulse.

The window needs to be conductive, thin enough to transmit the X-rays effectively, but thick and strong enough to minimize diffusion of the detector gas into the high vacuum of the monochromator chamber.

They are applicable in principle to longer wavelengths, but are limited by the problem of manufacturing a thin window capable of withstanding the high pressure difference.

Semiconductor detectors can be used in theory, and their applications are increasing as their technology improves, but historically their use for WDX has been restricted by their slow response (see EDX).

To derive the mass absorption accurately, data for the concentration of elements not measured by XRF may be needed, and various strategies are employed to estimate these.

Mixtures of multiple crystalline components in mineral powders can result in absorption effects that deviate from those calculable from theory.

The background signal in an XRF spectrum derives primarily from scattering of primary beam photons by the sample surface.

Confocal microscopy X-ray fluorescence imaging is a newer technique that allows control over depth, in addition to horizontal and vertical aiming, for example, when analysing buried layers in a painting.