X-bar theory

[7][8] It aimed to simplify and generalize the rules of grammar, addressing limitations of earlier phrase structure models.

X-bar theory was an important step forward because it simplified the description of sentence structure.

Earlier approaches needed many phrase structure rules, which went against the idea of a simple, underlying system for language.

X-bar theory offered a more elegant and economical solution, aligned with the thesis of generative grammar.

[9] Although recent work in the minimalist program has largely abandoned X-bar schema in favor of bare phrase structure approaches, the theory's central assumptions are still valid in different forms and terms in many theories of minimalist syntax.

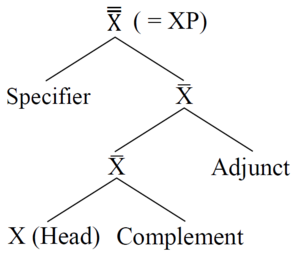

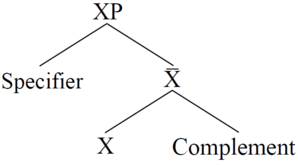

The X-bar schema consists of a head and its circumstantial components, in accordance with the headedness principle.

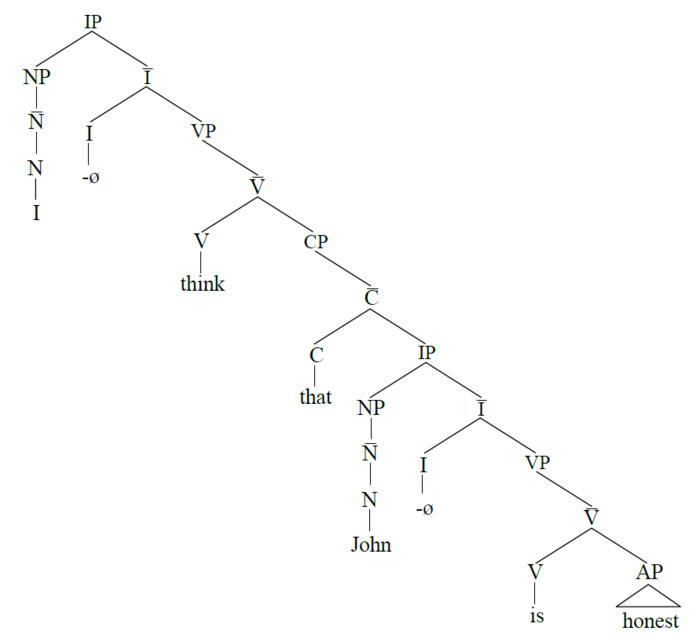

[18] Figure 5 suggests that syntactic structures are derived in a bottom-up fashion under the X-bar theory.

[20] Figures 1–5 are based on the word order of English, but the X-bar schema does not specify the directionality of branching because the binarity principle does not have a rule on it.

Accordingly, the X-bar theory, more specifically the binarity principle, does not impose a restriction on how a node branches.

ジョンがJohn-gaJohn-NOMリンゴをringo-oapple-ACC食べたtabe-taeat-PASTジョンが リンゴを 食べたJohn-ga ringo-o tabe-taJohn-NOM apple-ACC eat-PAST'John ate an apple'Finally the directionality of the specifier node is in essence unspecified as well, although this is subject to debate: Some argue that the relevant node is necessarily left-branching across languages, the idea of which is (partially) motivated by the fact that both English and Japanese have subjects on the left of a VP, whereas others such as Saito and Fukui (1998)[23] argue that the directionality of the node is not fixed and needs to be externally determined, for example by the head parameter.

[FN 5] The category I includes auxiliary verbs such as will and can, clitics such as -s of the third person singular present and -ed of the past tense.

This is consistent with the headedness principle, which requires that a phrase have a head, because a sentence (or a clause) necessarily involves an element that determines the inflection of a verb.

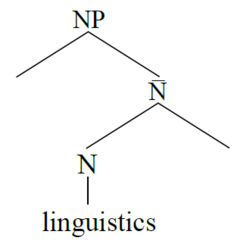

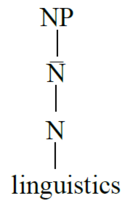

Assuming that S constitutes an IP, the structure of the sentence John studies linguistics at the university, for example, can be illustrated as in Figure 10.

[FN 6] As is obvious, the IP hypothesis makes it possible to regard the grammatical unit of sentence as a phrasal category.

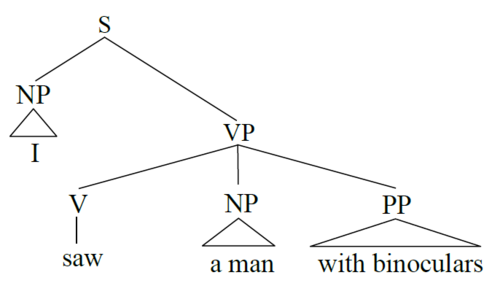

The X-bar theory, however, successfully captures the ambiguity as demonstrated in the configurations in Figure 14 and 15 below, because it assumes hierarchical structures in accordance with the binarity principle.