Historical race concepts

"[3] The word "race", interpreted to mean an identifiable group of people who share a common descent, was introduced into English in the 16th century from the Old French rasse (1512), from Italian razza: the Oxford English Dictionary cites the earliest example around the mid-16th century and defines its early meaning as a "group of people belonging to the same family and descended from a common ancestor".

(Snowden 1983; Lewis 1990)[pages needed] Classical civilizations from Rome to China tended to invest the most importance in familial or tribal affiliation rather than an individual's physical appearance (Dikötter 1992; Goldenberg 2003).

For example, a historian of the 3rd century Han dynasty in the territory of present-day China describes barbarians of blond hair and green eyes as resembling "the monkeys from which they are descended".

[8] (Graves 2001)[page needed] Hippocrates of Kos believed, as many thinkers throughout early history did, that factors such as geography and climate played a significant role in the physical appearance of different peoples.

"[10]European medieval models of race generally mixed Classical ideas with the notion that humanity as a whole was descended from Shem, Ham and Japheth, the three sons of Noah, producing distinct Semitic (Asiatic), Hamitic (African), and Japhetic (Indo-European) peoples.

[14] William Desborough Cooley's The Negro Land of the Arabs Examined and Explained (1841) has excerpts of translations of Khaldun's work that were not affected by French colonial ideas.

Bodin's color classifications were purely descriptive, including neutral terms such as "duskish colour, like roasted quinze", "black", "chestnut", and "farish white".

[22] "Finally, I am of opinion that after all these numerous instances I have brought together of negroes of capacity, it would not be difficult to mention entire well-known provinces of Europe, from out of which you would not easily expect to obtain off-hand such good authors, poets, philosophers, and correspondents of the Paris Academy; and on the other hand, there is no so-called savage nation known under the sun which has so much distinguished itself by such examples of perfectibility and original capacity for scientific culture, and thereby attached itself so closely to the most civilized nations of the earth, as the Negro.

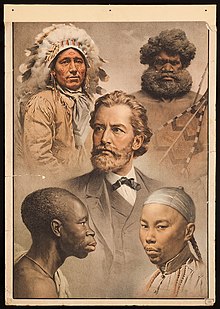

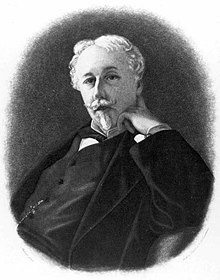

Among the 19th century naturalists who defined the field were Georges Cuvier, James Cowles Pritchard, Louis Agassiz, Charles Pickering (Races of Man and Their Geographical Distribution, 1848).

[25] Stefan Kuhl wrote that the eugenics movement rejected the racial and national hypotheses of Arthur Gobineau and his writing An Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races.

Different methods of eugenics, the study and practice of human selective breeding often with a race as a primary concentration, was still widely accepted in Britain, Germany, and the United States.

They believed that the phenotypical expression of an individual were determined by one's genes that are inherited through reproduction but there were certain social constructs, such as culture, environment, and language that were primary in shaping behavioral characteristics.

His stance in this case was considered to be quite radical in its time, because it went against the more orthodox and standard reading of the Bible in his time which implied all human stock descended from a single couple (Adam and Eve), and in his defense Agassiz often used what now sounds like a very "modern" argument about the need for independence between science and religion; though Agassiz, unlike many polygeneticists, maintained his religious beliefs and was not anti-Biblical in general.

Darwin's second book on evolution, The Descent of Man, features extensive argumentation addressing the single origin of the races, at times explicitly opposing Agassiz's theories.

He classified the populations of the Middle East, Central Asia, the Indian subcontinent, North Africa, and southern France as being racially mixed.

According to his definitions, the people of Spain, most of France, most of Germany, southern and western Iran as well as Switzerland, Austria, Northern Italy, and a large part of Britain, consisted of a degenerative race that arose from miscegenation.

His Melanochroi thus eventually also comprised various other dark Caucasoid populations, including the Hamites (e.g. Berbers, Somalis, northern Sudanese, ancient Egyptians) and Moors.

He also used the idea of races to argue for the continuity between humans and animals, noting that it would be highly implausible that man should, by mere accident acquire characteristics shared by many apes.

Darwin sought to demonstrate that the physical characteristics that were being used to define race for centuries (i.e. skin color and facial features) were superficial and had no utility for survival.

In The Descent of Man, Darwin noted the great difficulty naturalists had in trying to decide how many "races" there actually were: Man has been studied more carefully than any other animal, and yet there is the greatest possible diversity amongst capable judges whether he should be classed as a single species or race, or as two (Virey), as three (Jacquinot), as four (Kant), five (Blumenbach), six (Buffon), seven (Hunter), eight (Agassiz), eleven (Pickering), fifteen (Bory St. Vincent), sixteen (Desmoulins), twenty-two (Morton), sixty (Crawfurd), or as sixty-three, according to Burke.

His work put an emphasis on cultural and environmental effects on people to explain their development into adulthood and evaluated them in concert with human biology and evolution.

As a reaction to the rise of Nazi Germany and its prominent espousing of racist ideologies in the 1930s, there was an outpouring of popular works by scientists criticizing the use of race to justify the politics of "superiority" and "inferiority".

An influential work in this regard was the publication of We Europeans: A Survey of "Racial" Problems by Julian Huxley and A. C. Haddon in 1935, which sought to show that population genetics allowed for only a highly limited definition of race at best.

Another popular work during this period, "The Races of Mankind" by Ruth Benedict and Gene Weltfish, argued that though there were some extreme racial differences, they were primarily superficial, and in any case did not justify political action.

After returning to England from a tour of the United States in 1924, Huxley wrote a series of articles for the Spectator which he expressed his belief in the drastic differences between "negros" and "whites".

Although they argued that 'any biological arrangement of the types of European man is still largely a subjective process', they proposed that humankind could be divided up into "major" and "minor subspecies".

[28] Since Coon followed the traditional methods of physical anthropology, relying on morphological characteristics, and not on the emerging genetics to classify humans, the debate over Origin of Races has been "viewed as the last gasp of an outdated scientific methodology that was soon to be supplanted.

The statement was endorsed by Ernest Beaglehole, Juan Comas, L. A. Costa Pinto, Franklin Frazier, sociologist specialised in race relations studies, Morris Ginsberg, founding chairperson of the British Sociological Association, Humayun Kabir, writer, philosopher and Education Minister of India twice, Claude Lévi-Strauss, one of the founders of ethnology and leading theorist of structural anthropology, and Ashley Montagu, anthropologist and author of The Elephant Man: A Study in Human Dignity, who was the rapporteur.

This statement was the first to provide a definition of racism: "antisocial beliefs and acts which are based upon the fallacy that discriminatory intergroup relations are justifiable on biological grounds".

[54] In his 1984 article in Essence magazine, "On Being 'White' ... and Other Lies", James Baldwin reads the history of racialization in America as both figuratively and literally violent, remarking that race only exists as a social construction within a network of force relations: "America became white — the people who, as they claim, 'settled' the country became white — because of the necessity of denying the Black presence, and justifying the Black subjugation.