League of Communists of Yugoslavia

It was formed in 1919 as the main communist opposition party in the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes and after its initial successes in the elections, it was proscribed by the royal government and was at times harshly and violently suppressed.

After the liberation from foreign occupation in 1945, the party consolidated its power and established a one-party state, which existed in that form of government until 1990, a year prior to the start of the Yugoslav Wars and breakup of Yugoslavia.

After internal purges of pro-Soviet members, the party renamed itself the League of Communists in 1952 and adopted the politics of workers' self-management and an independent path to achieving socialism, known as Titoism.

[13] The Unification congress of the Socialist Labor Party of Yugoslavia (Communists) (Socijalistička radnička partija Jugoslavije (komunista), SRPJ(k)) was held in Belgrade on 20–23 April 1919 as consolidation on the left of the political spectrum.

A faction of the KPJ named Red Justice (Crvena pravda [sr]) attempted to assassinate the Regent Alexander on 28 June, and then killed former Interior Minister Milorad Drašković on 21 July.

[24][26] Despite the electoral success, the ban and KPJ's consequent move to covert operation took a heavy toll on the party in the next decade and a half when, faced with factional struggle, it would increasingly look to the Comintern for guidance.

This changed in 1925 when he was denounced by the leader of the Soviet Union Joseph Stalin personally before Yugoslav commission of the Comintern insisting that the KPJ must harness national movements for revolutionary aims.

Gorkić set about to introduce discipline to the KPJ top ranks and establish ties with the JSDS, the HSS, the Montenegrin Federalist Party, the Slovene Christian Socialists, and pro-Russian right wing organisations in Serbia with Moscow now advocating Yugoslav unity.

In addition to him, there were about 900 communists of Yugoslav origin or their supporters in the Soviet Union who fell victim to the Stalin's Great Purge as did 50 other KPJ officials posted in Moscow including Cvijić, Ćopić, Filipović, Marković, and Novaković.

[49] Tito worked with Pijade to arrange a compromise by including Đilas and Ranković in the temporary KPJ leadership along with Croatian moderate popular front supporters Kraš and Andrija Žaja as well as Soviet-educated Slovene Edvard Kardelj.

[52] In 1940, the KPJ successfully completed the campaign to diminish influence of Krleža and his literary adherents who were advocating Marxist ideas and opposed Stalinisation fearing totalitarianism.

[57] The final months of 1940 were marked by militarisation of politics in Yugoslavia leading to incidents such as the armed clash between the KPJ and the far-right Yugoslav National Movement in October leaving five dead and 120 wounded.

[58] The structural changes of the KPJ, strategic use of the national question and social emancipation to mobilise supporters made the party ideologically and operationally ready for armed resistance in the approaching war.

[60] With the Yugoslav defeat imminent, the KPJ instructed its 8,000 members to stockpile weapons in anticipation of armed resistance,[61] which would spread, by the end of 1941 to all areas of the country except Macedonia.

[64] The KPJ assessed that the German invasion of the Soviet Union had created favourable conditions for an uprising and its politburo founded the Supreme Headquarters of the National Liberation Army of Yugoslavia (Narodonooslobodilačka vojska Jugoslavije) with Tito as commander in chief on 27 June 1941.

[65] In terms of military training, the Partisans relied on those among its ranks who had completed the mandatory national service in the Royal Yugoslav Army or fought in the Spanish Civil War.

The move drew criticism from the Liberation Front of the Slovene Nation (Osvobodilna fronta slovenskega naroda, OF) civil resistance organisation – which accused the KPJ of creating its own army.

[72] KPJ's strategic approach was complex because of pressures from the Comintern prioritising social struggle competing with the national liberation in substantially regionally uneven circumstances resulting from Axis partitioning of Yugoslavia, especially from creation of Axis-satellite of the Independent State of Croatia (Nezavisna Država Hrvatska, NDH).

[76] In effect, Hebrang thus pursued a policy close to the wartime Soviet coalitionist views, supporting a certain level of involvement of the former members of the HSS, and the Independent Democratic Party, as well as representatives of associations and trade unions in the political life as a form of a "mass movement", including in the work of the State Anti-fascist Council for the National Liberation of Croatia as the top tier political body intended to grow into the future People's Parliament of Croatia.

Conclusion of the 1947 Bled Agreement seeking closer ties with Bulgaria,[107] and imminent deployment of Yugoslav Army to Albania prompted a political confrontation with the USSR.

[121] In 1950, Yugoslav authorities sought to combat unsustainable labour practices and improve production efficiency through introduction of workers' councils and the system which later became known as "socialist self-management".

[124] This led to codification of the reforms as 1953 Yugoslav constitutional amendments seeking to reflect the economic power of each constituent republic, while ensuring equal representation of each federal unit in the assembly to counterbalance this.

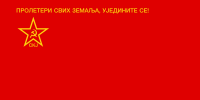

[125] The KPJ proclaimed shift from party monopolising power to the ideological leader of the society, decentralised its structure, and rebranded itself (and correspondingly its republican organisations) as the League of Communists of Yugoslavia (Savez komunista Jugoslavije, SKJ) at its sixth congress held in Zagreb in 1952.

Finally, at the 8th Congress of the SKJ held in 1964, Tito and Kardelj gave speeches criticising those thinking about merging nations of Yugoslavia as proponents of bureaucratic centralisation, unitarism and hegemony.

The ZKS in Slovenia and the SKH in Croatia favoured decentralisation and reduction of investment subsidies, and criticised the so-called political factories in Bosnia and Herzegovina and in Kosovo.

[144] Author Sabrina Ramet described the competing factions in the SKJ at the federal and republican levels in the 1962–87 period as "liberals" and "conservatives," based on whether they supported or opposed calls for decentralisation.

[145] An opposing camp was formed by the League of Communists of Serbia (Savez komunista Srbije, SKS), the SKBiH in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and the SKCG in Montenegro, who advocated continuing existing economic practices.

It was chaired by Krste Crvenkovski (Macedonia) and its members were Đuro Pucar (Bosnia), Blažo Jovanović (Montenegro), Dobrivoje Radosavljević (Serbia), Miko Tripalo (Croatia), and France Popit (Slovenia).

[164] The reformist forces grew in November 1968 when Marko Nikezić and Latinka Perović took helm of the SKS and advocated development through introduction of market economy practices and non-interference in other republics' affairs.

In Serbia, Marko Nikezić, Latinka Perović, Mirko Tepavac and Bora Pavlović were accused of liberalism, particularly with their refusal to condemn the Croatian Spring, reconcilability with public critique of federal centralisation and requests to weaken SKJ's party monopoly, as well as advocacy of democratic reforms of the socialist self-management in the country, and were forced to resign,[173] while Koča Popović retired out of solidarity with purged members of the party.