World War II in Yugoslavia

Shortly after Germany attacked the USSR on 22 June 1941,[27] the communist-led republican Yugoslav Partisans, on orders from Moscow,[27] launched a guerrilla liberation war fighting against the Axis forces and their locally established puppet regimes, including the Axis-allied Independent State of Croatia (NDH) and the Government of National Salvation in the German-occupied territory of Serbia.

Despite the setbacks, the Partisans remained a credible fighting force, with their organisation gaining recognition from the Western Allies at the Tehran Conference and laying the foundations for the post-war Yugoslav socialist state.

With support in logistics and air power from the Western Allies, and Soviet ground troops in the Belgrade offensive, the Partisans eventually gained control of the entire country and of the border regions of Trieste and Carinthia.

Genocide and ethnic cleansing was carried out by the Axis forces (particularly the Wehrmacht) and their collaborators (particularly the Ustaše and Chetniks), and reprisal actions from the Partisans became more frequent towards the end of the war, and continued after it.

Stojadinović was sacked by the regent Prince Paul in 1939 and replaced by Dragiša Cvetković, who negotiated a compromise with Croatian leader Vladko Maček in 1939, resulting in the formation of the Banovina of Croatia.

As this meant that each individual ethnic group would turn to movements opposed to the unity promoted by the South Slavic state, two different concepts of anti-Axis resistance emerged: the royalist Chetniks, and the communist-led Partisans.

It also gained control over the Italian governorate of Montenegro, and was granted the kingship in the Independent State of Croatia, though wielding little real power within it; although it did (alongside Germany) maintain a de facto zone of influence within the borders of the NDH.

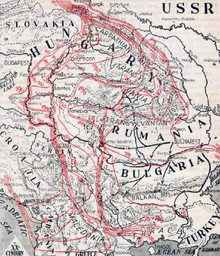

These major offensives were typically combined efforts by the German Wehrmacht and SS, Italy, Chetniks, the Independent State of Croatia, the Serbian collaborationist government, Bulgaria, and Hungary.

German troops, including the SS division "Prinz Eugen", on September 25 began to carry out a plan for the complete destruction of the Partisans in Primorska and Istria.

Even though today many circumstances, facts, and motivations remain unclear, intelligence reports resulted in increased Allied interest in Yugoslavia air operations and shifted policy.

In September 1943, at Churchill's request, Brigadier General Fitzroy Maclean was parachuted to Tito's headquarters near Drvar to serve as a permanent, formal liaison to the Partisans.

[64] The Seventh Enemy Offensive was the final Axis attack in western Bosnia in the spring of 1944, which included Operation Rösselsprung (Knight's Leap), an unsuccessful attempt to eliminate Josip Broz Tito personally and annihilate the leadership of the Partisan movement.

It called for a merge of the Partisan Anti-Fascist Council of National Liberation of Yugoslavia (Antifašističko V(ij)eće Narodnog Oslobođenja Jugoslavije, AVNOJ) and the Government in exile.

In late September 1944, three Bulgarian armies, some 455,000 strong in total led by General Georgi Marinov Mandjev, entered Yugoslavia with the strategic task of blocking the German forces withdrawing from Greece.

On 12 September, Peter II broadcast a message from London, calling upon all Serbs, Croats and Slovenes to "join the National Liberation Army under the leadership of Marshal Tito".

The Wehrmacht and the forces of the Ustaše-controlled Independent State of Croatia fortified a front in Syrmia that held through the winter of 1944–45 in order to aid the evacuation of Army Group E from the Balkans.

Having lost the easier withdrawal route through Serbia, they fought to hold the Syrmian front in order to secure the more difficult passage through Kosovo, Sandzak and Bosnia.

With large swaths of Bosnian, Croatian and Slovenian countryside already under Partisan guerrilla control, the final operations consisted in connecting these territories and capturing major cities and roads.

[47] Securing the rear areas were some 32,000 men of the Croatian gendarmerie (Hrvatsko Oružništvo), organised into 5 Police Volunteer Regiments plus 15 independent battalions, equipped with standard light infantry weapons, including mortars.

On 1 May, after capturing the Italian territories of Rijeka and Istria from the German LXXXXVII Corps, the Yugoslav 4th Army beat the western Allies to Trieste by one day.

Non-combat victims included the majority of the country's Jewish population, many of whom perished in concentration and extermination camps (e.g. Jasenovac, Stara Gradiška, Banjica, Sajmište, etc.)

The Ustashas, a Croatian ultranationalist and fascist movement which operated from 1929 to 1945 and was led by Ante Pavelić, gained control of the newly formed Independent State of Croatia (NDH) that was set up by the Germans after the invasion of Yugoslavia.

The event initiated the wave of Ustasha violence targeting Serbs that came in the following weeks and months, as massacres occurred in villages throughout the NDH,[105] particularly in Banija, Kordun, Lika, northwest Bosnia and eastern Herzegovina.

[110] By the end of 1941, along with Serbs and Roma, NDH authorities incarcerated the majority of the country's Jews in camps including Jadovno, Kruščica, Loborgrad, Đakovo, Tenja and Jasenovac.

[108] The Chetniks, a Serb royalist and nationalist movement which initially resisted the Axis[111] but progressively entered into collaboration with Italian, German and parts of the Ustasha forces, sought the creation of a Greater Serbia by cleansing non-Serbs, mainly Muslims and Croats from territories that would be incorporated into their post-war state.

To suppress the mounting resistance led by the Slovenian and Croatian Partisans, the Italians adopted tactics of "summary executions, hostage-taking, reprisals, internments and the burning of houses and villages.

[122] A number of Partisan units, and the local population in some areas, engaged in mass murder in the immediate postwar period against POWs and other perceived Axis sympathizers, collaborators, and/or fascists along with their relatives.

There were forced marches and execution of tens of thousands of captured soldiers and civilians (predominantly Croats associated with the NDH, but also Slovenes and others) fleeing their advance, in the Bleiburg repatriations.

[22] The late Jozo Tomasevich, Professor Emeritus of Economics at San Francisco State University, believes that the calculations of Kočović and Žerjavić "seem to be free of bias, we can accept them as reliable".

[132] Shortly after Kočović published his findings in Žrtve drugog svetskog rata u Jugoslaviji, Vladeta Vučković, a U.S. based college professor, claimed in a London-based émigré magazine that he had participated in the calculation of the number of victims in Yugoslavia in 1947.