Hungarian nobility

Although the Tripartitum – a frequently cited compilation of customary law published in 1514 – reinforced the idea that all noblemen were equal, the monarchs granted hereditary titles (mainly baron and count) to powerful aristocrats, and the poorest nobles lost their tax exemption from the mid-16th century.

The Habsburgs confirmed the nobles' privileges several times, but their attempts to strengthen royal authority regularly brought them into conflicts with the nobility, who represented nearly five percent of the population.

[13][14] The tribal leaders most probably bore the title úr (now "lord"), as it is suggested by Hungarian terms deriving from this word, such as ország (now "realm") and uralkodni ("to rule").

[17] The Magyars lived a nomadic or semi-nomadic life but archaeological research shows that most settlements consisted of small pit-houses and log cabins in the 10th century.

[23] The most widespread decorative motifs which can be regarded as tribal totems – the griffin, wolf and hind – were rarely applied in Hungarian heraldry in the following centuries.

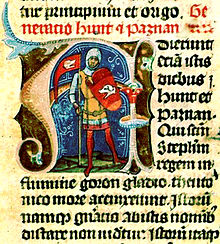

[25] The Gesta Hungarorum, a chronicle written around 1200, claimed that dozens of noble kindred flourishing in the late 12th century[note 2] had been descended from tribal leaders, but most modern scholars do not regard this list as a reliable source.

[54][55] Archaeologist Mária Wolf identifies the small motte forts, built on artificial mounds and protected by a ditch and a palisade that appeared in the 12th century, as the centers of private estates.

[58] The descendants of Otto Győr, the ispán of Somogy County remained wealthy landowners even after he donated 360 households to the newly established Zselicszentjakab Abbey in 1061.

[67] Béla III (r. 1172–1196) was the first Hungarian monarch to give away a whole county to a nobleman: he granted Modrus in Croatia to Bartholomew of Krk in 1193, stipulating that the grantee was to equip warriors for the royal army.

[68] Béla's son, Andrew II (r. 1205–1235), decided to "alter the conditions" of his realm and "distribute castles, counties, lands and other revenues" to his officials, as he narrated in a document in 1217.

[90][91] In the following decades, Béla IV of Hungary (r. 1235–1270) gave away large parcels of the royal demesne, expecting that the new owners would build stone castles there.

[99] That year "the nobles of all Hungary, called royal servants" persuaded Béla IV and his son, Stephen V (r. 1270–1272), to hold an assembly and confirm their collective privileges.

[103] Most warriors known as the "noble sons of servants" were descended from freemen or liberated serfs who received estates from Béla IV in Upper Hungary on the condition that they were to equip jointly a fixed number of knights.

[108] Impoverished noblemen had little chance to receive land grants from the kings, because they were unable to participate in the monarchs' military campaigns,[110] but commoners who bravely fought in the royal army were regularly ennobled.

[118][119] A familiaris was a nobleman who entered into the service of a wealthier landowner in exchange for a fixed salary or a portion of revenue, or rarely for the ownership or usufruct (right to enjoyment) of a piece of land.

To restore public order, the prelates convoked the barons and the delegates of the noblemen and the nomadic Cumans who had settled in Hungary to a general assembly near Pest in 1277.

[128] When Andrew III (r. 1290–1301), the last male member of the Árpád dynasty, died in 1301, about a dozen lords[note 6] held sway over most parts of the kingdom.

[146] Louis I emphasized all noblemen enjoyed "one and the selfsame liberty" in his realms[143] and secured all privileges that nobles owned in Hungary proper to their Slavonian and Transylvanian peers.

[148] The vast majority of the Upper Hungarian "noble sons of servants" achieved the status of true noblemen without a formal royal act, because the memory of their conditional landholding fell into oblivion.

[152] Louis decreed that only Catholic noblemen and knezes could hold landed property in the district of Karánsebes (now Caransebeș in Romania) in 1366, but Eastern Orthodox landowners were not forced to convert to Catholicism in other territories of the kingdom.

[182][183] After he died in 1439, a civil war broke out between the partisans of his son, Ladislaus the Posthumous (r. 1440–1457), and the supporters of the child king's rival, Vladislaus III of Poland (r. 1440–1444).

[220] The sultan allowed Zápolya's widow, Isabella Jagiellon (d. 1559), to rule the lands east of the river Tisza on behalf of her infant son, John Sigismund (r. 1540–1571), in return for a yearly tribute.

The palatine, Prince Paul Esterházy (d. 1713), convinced the monarch to reduce the noblemen's tax burden to 0.25 million florins, but the difference was to be paid by the peasantry.

[250] Although the rebels were forced to yield, the Treaty of Szatmár granted a general amnesty for them and the new Habsburg monarch, Charles III (r. 1711–1740), promised to respect the privileges of the Estates of the realm.

[264] The jurist Mihály Bencsik claimed that the burghers of Trencsén (now Trenčín in Slovakia) should not send delegates to the Diet because their ancestors had been forced to yield to the conquering Magyars in the 890s.

[298] Count István Széchenyi (d. 1860) demanded the abolition of the serfs' labour service and the entail system, stating that, "We, well-to-do landowners are the main obstacles to the progress and greater development of our fatherland".

[324] The advisors of the young emperor, Franz Joseph (r. 1848–1916), declared that Hungary had lost its historic rights and the conservative Hungarian aristocrats[note 16] could not persuade him to restore the old constitution.

[326][327] The vast majority of noblemen opted for a passive resistance: they did not hold offices in state administration and tacitly obstructed the implementation of imperial decrees.

[334] Next year, the Croatian–Hungarian Settlement restored the union of Hungary proper and Croatia, but secured the competence of the Croatian sabor in internal affairs, education and justice.

[351] The Hungarian National Council adopted a land reform setting the maximum size of the estates at 1.15 square kilometres (280 acres) and ordering the distribution of any excess among the local peasantry.