Zero field NMR

ZULF NMR experiments typically involve the use of passive or active shielding to attenuate Earth’s magnetic field.

There are a number of advantages to operating in this regime: magnetic-susceptibility-induced line broadening is attenuated which reduces inhomogeneous broadening of the spectral lines for samples in heterogeneous environments.

Another advantage is that the low frequency signals readily pass through conductive materials such as metals due to the increased skin depth; this is not the case for high-field NMR for which the sample containers are usually made of glass, quartz or ceramic.

[2] High-field NMR employs inductive detectors to pick up the radiofrequency signals, but this would be inefficient in ZULF NMR experiments since the signal frequencies are typically much lower (on the order of hertz to kilohertz).

The development of highly sensitive magnetic sensors in the early 2000s including SQUIDs, magnetoresistive sensors, and SERF atomic magnetometers made it possible to detect NMR signals directly in the ZULF regime.

Previous ZULF NMR experiments relied on indirect detection where the sample had to be shuttled from the shielded ZULF environment into a high magnetic field for detection with a conventional inductive pick-up coil.

One successful implementation was using atomic magnetometers at zero magnetic field working with rubidium vapor cells to detect zero-field NMR.

This can be as simple as polarizing the spins in a magnetic field followed by shuttling to the ZULF region for signal acquisition, and alternative chemistry-based hyperpolarization techniques can also be used.

), which in the case of liquid-state nuclear magnetic resonance may be split into two major terms.

) corresponds to the Zeeman interaction between spins and the external magnetic field, which includes chemical shift (

denotes the isotropic part of the chemical shift for the a-th spin;

(and therefore the spin dynamics behavior of such a system) depends on the magnetic field.

An alternative approach is to use hyperpolarization techniques, which are chemical and physical methods to generate nuclear spin polarization.

NMR experiments require creating a transient non-stationary state of the spin system.

In ZULF experiments, constant magnetic field pulses are used to induce non-stationary states of the spin system.

In the simple case of a heteronuclear pair of J-coupled spins, both these excitation schemes induce a transition between the singlet and triplet-0 states, which generates a detectable oscillatory magnetic field.

[7] NMR signals are usually detected inductively, but the low frequencies of the electromagnetic radiation emitted by samples in a ZULF experiment makes inductive detection impractical at low fields.

Hence, the earliest approach for measuring zero-field NMR in solid samples was via field-cycling techniques.

[8] The field cycling involves three steps: preparation, evolution and detection.

In the preparation stage, a field is applied in order to magnetize the nuclear spins.

Then the field is suddenly switched to zero to initiate the evolution interval and the magnetization evolves under the zero-field Hamiltonian.

The time-varying magnetization can be detected by repeating the field cycle with incremented lengths of the zero-field interval, and hence the evolution and decay of the magnetization is measured point by point.

The Fourier transform of this magnetization will result to the zero-field absorption spectrum.

The emergence of highly sensitive magnetometry techniques has allowed for the detection of zero-field NMR signals in situ.

Examples include superconducting quantum interference devices (SQUIDs), magnetoresistive sensors, and SERF atomic magnetometers.

SQUIDs have high sensitivity, but require cryogenic conditions to operate, which makes them practically somewhat difficult to employ for the detection of chemical or biological samples.

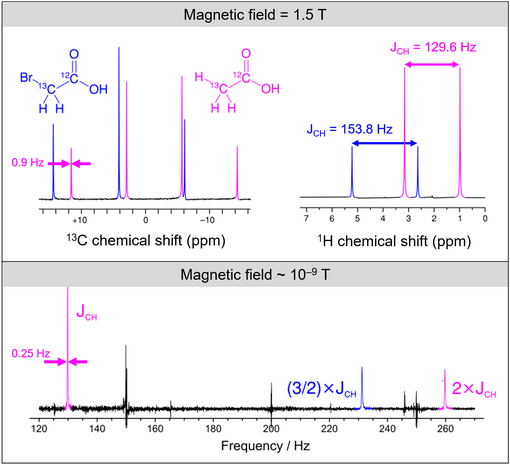

The boundaries between zero-, ultralow-, low- and high-field NMR are not rigorously defined, although approximate working definitions are in routine use for experiments involving small molecules in solution.

The boundary between low and high field is more ambiguous and these terms are used differently depending on the application or research topic.

In the context of ZULF NMR, the boundary is defined as the field at which chemical shift differences between nuclei of the same isotopic species in a sample match the spin-spin couplings.

Note that these definitions strongly depend on the sample being studied, and the field regime boundaries can vary by orders of magnitude depending on sample parameters such as the nuclear spin species, spin-spin coupling strengths, and spin relaxation times.