Zirconium alloys

[2] The water cooling of reactor zirconium alloys elevates requirement for their resistance to oxidation-related nodular corrosion.

[3] The hydrides are less dense and are weaker mechanically than the alloy; their formation results in blistering and cracking of the cladding – a phenomenon known as hydrogen embrittlement.

Upon annealing below the phase transition temperature (α-Zr to β-Zr) the grains are equiaxed with sizes varying from 3 to 5 μm.

A sub-micrometer thin layer of zirconium dioxide is rapidly formed in the surface and stops the further diffusion of oxygen to the bulk and the subsequent oxidation.

This oxidation is accelerated at high temperatures, e.g. inside a reactor core if the fuel assemblies are no longer completely covered by liquid water and insufficiently cooled.

It also closely resembles the anaerobic oxidation of iron by water (reaction used at high temperature by Antoine Lavoisier to produce hydrogen for his experiments).

[21][22] In case of loss-of-coolant accident (LOCA) in a damaged nuclear reactor, hydrogen embrittlement accelerates the degradation of the zirconium alloy cladding of the fuel rods exposed to high temperature steam.

[24] Zirconium has a hexagonal close-packed crystal structure (HCP) at room temperature, where 〈𝑎〉prismatic slip has the lowest critical resolved shear stress.

[31] 〈𝑎〉basal slip in high purity single crystal Zr deformed at a low strain rate of 10−4 s−1 was only seen at temperatures above 550 °C.

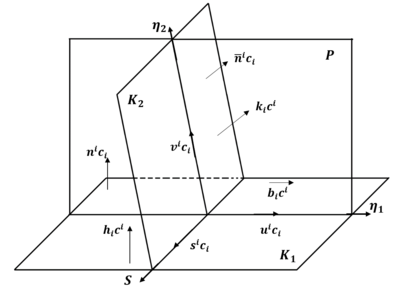

Deformation twins in Zr are generally lenticular in shape, lengthening in the 𝜼𝟏 direction and thickening along the 𝑲𝟏 plane normal.

The axis-angle misorientation relationship between the parent and twin is a rotation of angle 𝜉 about the shear plane's normal direction 𝑷.

[41] Due to symmetry in the HCP crystal structure, six crystallographically equivalent twin variants exist for each type.

Still, they can be distinguished apart using their absolute orientations with respect to the loading axis, and in some cases (depending on the sectioning plane), the twin boundary trace.

The primary twin type formed in any sample depends on the strain state and rate, temperature and crystal orientation.

In macroscopic samples, this is typically influenced strongly by the crystallographic texture, grain size, and competing deformation modes (i.e., dislocation slip), combined with the loading axis and direction.

[32] Kaschner and Gray[44] observe that yield stress increases with increasing strain rate in the range of 0.001 s−1 and 3500 s−1, and that the strain rate sensitivity in the yield stress is higher when uniaxially compressing along texture components with predominantly prismatic planes than basal planes.

They conclude that the rate sensitivity of the flow stress is consistent with Peierls forces inhibiting dislocation motion in low-symmetry metals during slip-dominated deformation.

[45] Samples compressed along texture components with predominantly prismatic planes yield at lower stresses than texture components with predominantly basal planes,[44] consistent with the higher critical resolved shear stress for <𝑐 + 𝑎> pyramidal slip compared to <𝑎> prismatic slip.

At quasi-static strain rates, McCabe et al.[35] only observed T1 twinning in samples compressed along a plate direction with a prismatic texture component along the loading axis.

Knezevic et al.[36] fitted experimental data of high-purity polycrystalline Zr to a self-consistent viscoplastic model to study slip and twinning systems' rate and temperature sensitivity.

[6] In one particular application, a Zr-2.5Nb alloy is formed into a knee or hip implant and then oxidized to produce a hard ceramic surface for use in bearing against a polyethylene component.

This oxidized zirconium alloy material provides the beneficial surface properties of a ceramic (reduced friction and increased abrasion resistance), while retaining the beneficial bulk properties of the underlying metal (manufacturability, fracture toughness, and ductility), providing a good solution for these medical implant applications.

[48] Zr702 is a commercially pure grade,[49] widely used for its high corrosion resistance and low neutron absorption, particularly in nuclear and chemical industries.

[50] Zr705, alloyed with 2-3% niobium, shows enhanced strength and crack resistance and is used for high-stress applications such as demanding chemical processing environments, and medical implants.