1,3-Dipolar cycloaddition

1,3-dipolar cycloaddition is an important route to the regio- and stereoselective synthesis of five-membered heterocycles and their ring-opened acyclic derivatives.

[4] After much debate, the former proposal is now generally accepted[5]—the 1,3-dipole reacts with the dipolarophile in a concerted, often asynchronous, and symmetry-allowed π4s + π2s fashion through a thermal six-electron Huckel aromatic transition state.

A more accurate method to describe the electronic distribution on a 1,3-dipole is to assign the major resonance contributor based on experimental or theoretical data, such as dipole moment measurements[9] or computations.

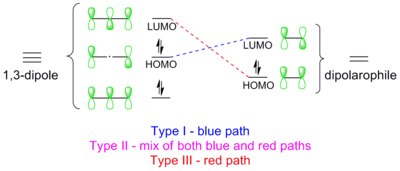

[11][12][13] In 1,3-dipolar cycloadditions, identity of the dipole-dipolarophile pair determines whether the HOMO or the LUMO character of the 1,3-dipole will dominate (see discussion on frontier molecular orbitals below).

Other examples of dipolarophiles include fullerenes and nanotubes, which can undergo 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition with azomethine ylide in the Prato reaction.

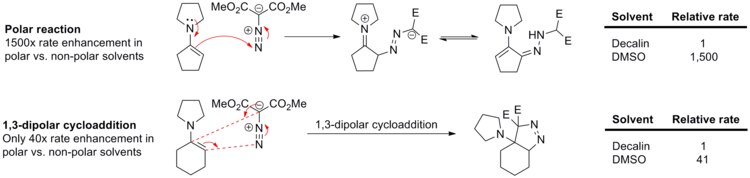

For example, the rate of reaction between phenyl diazomethane and ethyl acrylate or norbornene (see scheme below) changes only slightly upon varying solvents from cyclohexane to methanol.

On the other hand, a close analog of this reaction, N-cyclohexenyl pyrrolidine 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition to dimethyl diazomalonate, is sped up only 41-fold in DMSO relative to decalin.

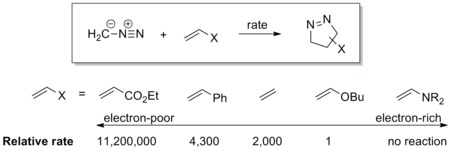

Diazomethane reacts with the electron-poor ethyl acrylate more than a million times faster than the electron rich butyl vinyl ether.

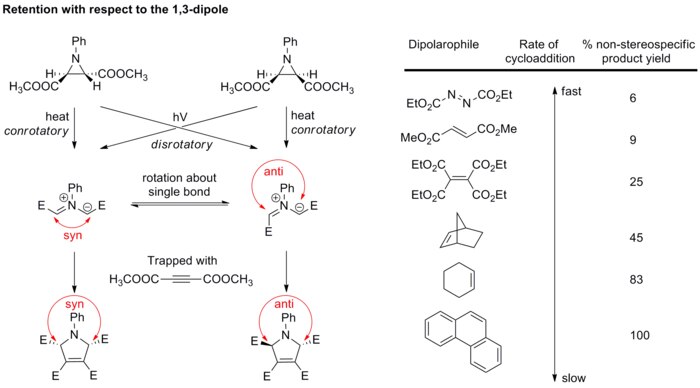

Diastereopure azomethine ylides are generated by electrocyclic ring opening of aziridines, and then rapidly trapped with strong dipolarophiles before bond rotation can take place (see scheme below).

In the transition state, the phenyl and the methyl ester groups stack to give the cis-substitution as the exclusive final pyrroline product.

The example below shows addition of nitrile oxide to an enantiomerically pure allyl alcohol in the presence of a magnesium ion.

[34] 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reactions have emerged as powerful tools in the synthesis of complex cyclic scaffolds and molecules for medicinal, biological, and mechanistic studies.

Among them, [3+2] cycloaddition reactions involving carbonyl ylides have extensively been employed to generate oxygen-containing five-membered cyclic molecules.

[39] An initial tautomerization occurs, followed by elimination of the leaving group to aromatize the pyrone ring and to generate the carbonyl ylide.

A universal approach for generating carbonyl ylides involves metal catalysis of α-diazocarbonyl compounds, generally in the presence of dicopper or dirhodium catalysts.

[45][46] The universality and extensive use of 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reactions mediated by metal catalysis of diazocarbonyl molecules, for synthesizing oxygen-containing five-membered rings, has spurred significant interest into its mechanism.

Therefore, a persistent metallocarbene can influence the stereoselectivity and regioselectivity of the 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reaction based on the stereochemistry and size of the metal ligands.

The mechanism of the 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reaction between the carbonyl ylide dipole and alkynyl or alkenyl dipolarophiles has been extensively investigated with respect to regioselectivity and stereoselectivity.

[54][55] Regioselectivity of 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reactions between carbonyl ylide dipoles and alkynyl or alkenyl dipolarophiles is essential for generating molecules with defined regiochemistry.

FMO theory and analysis of the HOMO-LUMO energy gaps between the dipole and dipolarophile can rationalize and predict the regioselectivity of experimental outcomes.

The archetypal regioselectivity of the 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reaction mediated by carbonyl ylide dipoles has been examined by Padwa and coworkers.

One early example conferred stereoselectivity in terms of endo and exo products with metal catalysts and Lewis acids.

The endo selectivity observed for Lewis acid cycloaddition reactions is attributed to the optimized orbital overlap of the carbonyl π systems between the dipolarophile coordinated by Yb(Otf)3 (LUMO) and the dipole (HOMO).

After many investigations, two primary approaches for influencing the stereoselectivity of carbonyl ylide cycloadditions have been developed that exploit the chirality of metal catalysts and Lewis acids.

[64][65] This reaction is also bioorthogonal: azides and alkynes are both generally absent from biological systems and therefore these functionalities can be chemoselectively reacted even in the cellular context.

Although copper(I) is toxic, many protective ligands have been developed to both reduce cytotoxicity and improve rate of CuAAC, allowing it to be used in in vivo studies.

[66] For example, Bertozzi et al. reported the metabolic incorporation of azide-functionalized saccharides into the glycan of the cell membrane, and subsequent labeling with fluorophore-alkyne conjugate.

[67] To avoid toxicity of copper(I), Bertozzi et al. developed the strain-promoted azide-alkyne cycloaddition (SPAAC) between organic azide and strained cyclooctyne.

The angle distortion of the cyclooctyne helps to speed up the reaction by both reducing the activation strain and enhancing the interactions, thereby enabling it to be used in physiological conditions without the need for the catalyst.

[68] For instance, Ting et al. introduced an azido functionality onto specific proteins on the cell surface using a ligase enzyme.