1960 South Vietnamese coup attempt

They also bemoaned the politicisation of the military, whereby regime loyalists who were members of the Ngô family's covert Cần Lao Party were readily promoted ahead of more competent officers who were not insiders.

Đông was supported in the conspiracy by his brother-in-law Lieutenant Colonel Nguyen Trieu Hong, whose uncle was a prominent official in a minor opposition party.

After initially being trapped inside the Independence Palace, Diệm stalled the coup by holding negotiations and promising reforms, such as the inclusion of military officers in the administration.

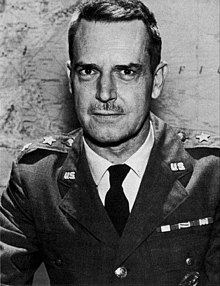

The revolt was led by 28-year-old Lieutenant Colonel Vương Văn Đông,[1] a northerner, who had fought with the French Union forces against the Viet Minh during the First Indochina War.

[7] They felt that politically minded officers, who joined Diệm's secret Catholic-dominated Cần Lao Party, which was used to control South Vietnamese society, were rewarded with promotion rather than those most capable.

[10] Many months before the coup, Đông had met Diệm's brother and adviser Ngô Đình Nhu, widely regarded as the brains of the regime, to ask for reform and de-politicisation of the army.

An intelligence report prepared by the US State Department in late August claimed the "worsening of internal security, the promotion of incompetent officers and Diệm's direct interference in army operations ... his political favoritism, inadequate delegation of authority, and the influence of the Can Lao".

[11] It also claimed that discontent with Diệm among high-ranking civil servants was at their highest point since the president had established in power, and that the bureaucrats wanted a change of leadership, through a coup if needed.

[12] Around this time, Durbrow began to advise Diệm to remove Nhu and his wife from the government, basing his arguments on a need to cultivate broad popular support to make South Vietnam more viable in the long term.

[14] According to Stanley Karnow, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of Vietnam: A History, the coup was ineffectively executed;[2] although the rebels captured the headquarters of the Joint General Staff near Tan Son Nhut Air Base,[4] they failed to follow the textbook tactics of blocking the roads leading into Saigon.

A rebel machine gun fired into Diệm's bedroom window from the adjacent Palais de Justice and penetrated his bed, but the president had arisen just a few minutes earlier.

[5] Brigadier General Nguyễn Khánh, at the time the ARVN Chief of Staff, climbed over the palace wall to reach Diệm during the siege,[19] as the Presidential Guard had been under explicit orders to not open the gates.

[6] They wanted officers and opposition figures to be appointed to a new government to keep Diệm in check,[9] but with Hong—who was meant to supposed to be the primary negotiator—dead, Dong was uncertain as to what to demand.

[22] Đán spoke on Radio Vietnam and staged a media conference during which a rebel paratrooper pulled a portrait of the president from the wall, ripped it and stamped on it.

[18] The Fifth Division of Colonel Nguyễn Văn Thiệu, a future president, brought infantry forces from Biên Hòa, a town north of Saigon.

[29] Assistant Secretary of Defense Nguyễn Đình Thuận phoned Durbrow and discussed the impending standoff between the incoming loyalists and the rebels.

[29] In the meantime, loyalist forces continued to head towards the capital, while the rebels publicly claimed on radio that Diệm had surrendered in an apparent attempt to attract more troops to their cause.

The paratroopers became outnumbered and were forced to retreat to defensive positions around their barracks, which was an ad hoc camp that had been set up in a public park approximately 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) away.

Diệm promptly reneged on his promises, and began rounding up scores of critics, including several former cabinet ministers and some of the Caravelle Group of 18 who had released a petition calling for reform.

[27] He had previously thought the Americans had full support for him, but afterwards, he told his confidants that he felt like Syngman Rhee, the President of the anti-communist South Korea who had been strongly backed by Washington until being deposed earlier in 1960, a regime change Diệm saw as US-backed.

[10] In the wake of the failed coup, Diệm blamed Durbrow for a perceived lack of US support, while his brother Nhu further accused the ambassador of colluding with the rebels.

Colonel Edward Lansdale, a CIA agent who helped entrench Diệm in power in 1955, ridiculed Durbrow's comments and called on the Eisenhower administration to recall the ambassador.

[31] McGarr had been in contact with both the rebel and loyalist units during the standoff and credited the failure of the coup to the "courageous action of Diệm coupled with loyalty and versatility of commanders bringing troops into Saigon".

[33] McGarr asserted that "Diệm has emerged from this severe test in position of greater strength with visible proof of sincere support behind him both in armed forces and civilian population.

[28] Carver had also spent some of the coup period in a meeting with civilian rebel leaders at Thuy's house, although it is not known if he pro-actively encouraged Diệm opponents.

[28] The Americans thought that Nhu was the real culprit, but told the Ngô family that they were removing Carver from the country for his own safety, thereby allowing all parties to avoid embarrassment.

[33] However, in December, the Assistant Secretary of State for Far Eastern Affairs J. Graham Parsons told Durbrow to stop, cabling "Believe for present Embassy has gone as far as feasible in pushing for liberalization and future exhortation likely to be counterproductive.

[6] However, Minh did not come to assist Diệm, and the president responded by appointing him to the post of Presidential Military Advisor, where he had no influence or troops to command in case the thought of coup ever crossed his mind.

[28][38] Minh and Lieutenant General Tran Van Don, the commander of the 1st Division in central Vietnam, but who was in Saigon when the coup attempt occurred, were the subject of a military investigation by the regime, but were cleared of involvement by junior officers appointed by Diem.

He left a death note stating "I also will kill myself as a warning to those people who are trampling on all freedom", referring to Thích Quảng Đức, the monk who self-immolated in protest against Diệm's persecution of Buddhism.