African military systems before 1800

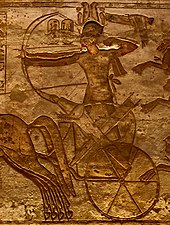

Hyksos technology was superior to that of the Egyptians, including more durable weapons of bronze (rather than the weaker copper), body armor, scimitars, and most devastatingly, the horse drawn chariot.

Mobilization of traditional weapons and fighting units reversed the Hyskos triumph including the campaigns of Seqenenre Tao (who died as a result of combat or capture) and the decisive military initiatives of his son and successor Kamose, which rolled back the Hyksos northward, and ravaged a merchant fleet beneath the walls of their capital Avaris.

In the First Punic War, the Roman general Marcus Atilius Regulus decided to bring the campaign directly to African soil, hoping to crush Carthage right in its own ground (256–255 BC).

Carthage rejected harsh peace terms by Regulus, and reformed its army, adding fresh contingents, including Greeks, native levies, and the veteran troops of Hamilcar's Sicilian campaign.

He was also forced to do battle with a relatively uncoordinated blend of Gallic and Spanish mercenary troops, local African levies, and the remaining battle-hardened veterans of the Italian campaign.

[18] His force was divided into three separate echelons- mercenaries in the first line, native levies in the second, and the old guard, the veterans of Italy (a mix of African, Gallic, Italic and Spanish fighting men) in the third.

Later Sudanic based forces like the Blemmye also deployed horses and camels for their raids over the Egyptian frontier, and the poisoned arrow tactics of their predecessors found ready employment.

[23] The Kushites penetrated as far south as the Aswan area, defeating three Roman cohorts, conquering Syene, Elephantine and Philae, capturing thousands of Egyptians, and overthrowing bronze statutes of Augustus recently erected there.

The head of one of these Augustian statutes was carried off to Meroe as a trophy, and buried under a temple threshold of the Candace Amanirenas, to commemorate the Kushite victory, and symbolically tread on her enemies.

The Kushites too appear to have found nomads like the Blemmyes to be a problem, allowed Rome monitoring and staging outposts against them, and even conducted joint military operations with the Romans in later years against such mauraders.

For almost 600 years, the powerful bowmen of the region created a barrier for Muslim expansion into the northeast of the African continent, fighting off multiple invasions and assaults with stinging swarms of arrows.

Both infantry and cavalry forces were well represented on the African continent in the pre-colonial era, and the introduction of both horses and guns in large numbers was to have important implications for military systems.

The primacy of such warriors, together with those who wielded the spear, was challenged by the coming of horses, increasingly introduced around the 14th century to the flat country of the Sahel and Saharan regions, and the savannas of northern West Africa.

Rising quantities of guns are associated with increases in the slave trade, as major powers such as Dahomey, Benin and Ashanti stepped up their conquests to feed the insatiable demand for human bodies.

The psychological impact of guns in the night and dawn attacks favored by slave raiders was significant, and in slave-catching, flintlocks could also be loaded with shot, wounding and crippling victims rather than killing them outright.

[49] These entities, sometimes directly supplied with firearms by European or Arab/North African slave dealers, ranged widely in the regions where they operated, creating massive turmoil and insecurity, particularly where strong centralized states that could protect their subjects did not exist, or were weak.

Portuguese troops often turned in excellent performances, but written sources sometimes exaggerate the number of native enemies defeated, giving a misleading picture of the military situation.

[55] It is clear that firearms conferred an undoubted tactical advantage both in African and European battlefields,[56] but such success was influenced by other factors such as terrain, weather, morale and the enemy response.

[55][57] In the Zambezi basin in 1572 for example, a 600-man force of Portuguese arquebusiers, supplemented with cannon, formed a disciplined square, and defeated several thousand Africans armed with bows, spears and axes.

[64] Cavalry was the elite arm of the force and provided the stable nucleus of an army that when fully mobilized numbered some 100,000 effectives, spread throughout the empire, between the northern and southern wings.

[41] Firepower gave the gun-armed footman growing influence, not only as far as bullets delivered, but the fact that the noise and smoke of muskets could frighten horses in the enemy camp, creating a tactical advantage; this happened when Asante gunmen confronted the horsemen of Gonja in the 17th century.

Yoruba fortifications were often protected with a double wall of trenches and ramparts, and in the Congo forests concealed ditches and paths, along with the main works, often bristled with rows of sharpened stakes.

The bulk of the fighting hosts were made of up general purpose levies and volunteers, but most Kongo polities maintained a small core of dedicated soldiers- nucleus of a standing army.

A complex system of drums, horns and signals aided in maneuver of the warrior hosts, and distinctive battle-flags and pennants identified the location of elite troops or their commanders.

[57] While Portuguese mercenaries and armies armed with muskets made a substantial showing in military terms, it was only until the end of the 18th century than indigenous forces incorporated them on a large scale.

According to Polybius, the Romans seized a shipwrecked Carthaginian warship, and used it as a blueprint for a massive naval build-up, adding its own refinements – the corvus – which allowed an enemy vessel to be "gripped" and boarded for hand-to-hand fighting.

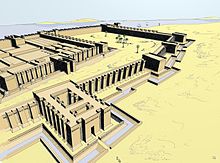

Control of war canoes seem to have become more centralized as rising southern hegemons began to dominate the freer-wheeling trade and raiding of earlier Nile River times, according to one Australian naval study of ancient Egyptian maritime power.

Over the next several decades Somali-Portuguese tensions would remain high and the increased contact between Somali sailors and Ottoman corsairs worried the Portuguese, prompting the latter to send a punitive expedition against Mogadishu under Joao de Sepuvelda.

[97] Where local peoples collaborated, or a centralized polity could mobilize resources to fight, coast watching systems developed over time that could move warnings some 50 to 60 miles a day overland when news of a hostile European ship incursion was received.

Angola serves as a test bed in many ways for outside technology in African warfare, and the Portuguese attempted direct conquest with their own weapons, including the use of heavy body armor.