History of agriculture in the United States

Beginning in 1620, the first settlers in Plymouth Colony planted barley and peas from England but their most important crop was Indian corn (maize) which they were shown how to cultivate by the native Squanto.

Merchants and artisans hired teen-aged indentured servants, paying the transportation over from Europe, as workers for a domestic system for the manufacture of cloth and other goods.

Merchants often bought wool and flax from farmers and employed newly arrived immigrants who had been textile workers in Ireland and Germany to work in their homes spinning the materials into yarn and cloth.

[8][9] Westward expansion, including the Louisiana Purchase and American victory in the War of 1812 plus the building of canals and the introduction of steamboats opened up new areas for agriculture.

[12] In New England, subsistence agriculture gave way after 1810 to production to provide food and dairy supplies for the rapidly growing industrial towns and cities.

St. Louis, Missouri was the largest town on the frontier, the gateway for travel westward, and a principal trading center for Mississippi River traffic and inland commerce.

The conservatives and Whigs, typified by president John Quincy Adams, wanted a moderated pace that charged the newcomers enough to pay the costs of the federal government.

Hacker describes that in Kentucky about 1812: Farms were for sale with from ten to fifty acres cleared, possessing log houses, peach and sometimes apple orchards, inclosed in fences, and having plenty of standing timber for fuel.

It was, not his fear of a too close contact with the comforts and restraints of a civilized society that stirred him into a ceaseless activity, nor merely the chance of selling out at a profit to the coming wave of settlers; it was his wasting land that drove him on.

[20] A dramatic expansion in farming took place from 1860 to 1910 as cheap rail transportation replaced long wagon trips and opened the way for sales to Eastern cities and exports to Europe.

The character of soils and climate in the lower South hindered the creation of pastures, so the mule breeding industry was concentrated in the border states of Missouri, Kentucky, and Tennessee.

Rapid growth infused the national organization with money from dues, and many local granges established consumer cooperatives, initially supplied by the Chicago wholesaler Aaron Montgomery Ward.

The birth of the federal government's Cooperative Extension Service, Rural Free Delivery, and the Farm Credit System were largely due to Grange lobbying.

The rapid expansion of the farms coupled with the diffusion of trucks and Model T cars, and the tractor, allowed the agricultural market to expand to an unprecedented size.

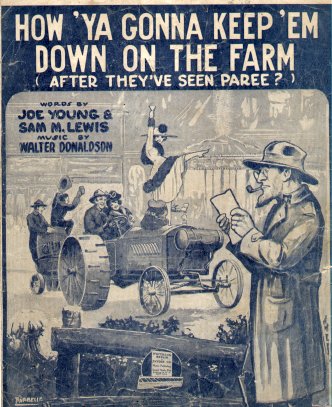

A popular Tin Pan Alley song of 1919 asked, concerning the United States troops returning from World War I, "How Ya Gonna Keep 'em Down on the Farm (After They've Seen Paree)?".

Farmers had enjoyed a period of prosperity as U.S. farm production expanded rapidly to fill the gap left as European belligerents found themselves unable to produce enough food.

Hoover advocated the creation of a Federal Farm Board which was dedicated to restriction of crop production to domestic demand, behind a tariff wall, and maintained that the farmer's ailments were due to defective distribution.

Major programs addressed to their needs included the Resettlement Administration (RA), the Rural Electrification Administration (REA), rural welfare projects sponsored by the WPA, NYA, Forest Service and CCC, including school lunches, building new schools, opening roads in remote areas, reforestation, and purchase of marginal lands to enlarge national forests.

[104] Individuals with prominent roles in farm worker organizing in this period include Cesar Chavez, Dolores Huerta, Larry Itliong, and Philip Vera Cruz.

[106] In 2015, grain farmers started taking "an extreme step, one not widely seen since the 1980s" by breaching lease contracts with their landowners, reducing the amount of land they sow and risking long legal battles with landlords.

[102]: 107 Electricity also played a role in making major innovations in animal husbandry possible, especially modern milking parlors, grain elevators, and CAFOs (confined animal-feeding operations).

The publication of Rachel Carson's Silent Spring in 1962 energized the environmental movement and brought a new awareness in how industrialized agriculture misused the available land with dangerous chemicals.

Decades of suburbanization, rapid national and global population growth, renewed worries about soil erosion, fears of oil and water shortages, and the sudden increase in farm exports beginning in 1972 all were worrisome threats to the long-term supply of good farmland.

The Carter administration in the late 1970s supported initiatives like the National Agricultural Lands Survey and liberals in Congress introduced legislation to control suburban sprawl.

Therefore, successful farmers, especially on the Great Plains, bought up as much land as possible, purchased very expensive mechanical equipment, and depended on migrating hired laborers at harvesting time.

Thanks to these innovations, vast expanses of the wheat belt now support commercial production, and yields have resisted the negative impact of insects, diseases, and weeds.

[117] In the late 19th century, hardy new wheat varieties from the Russian steppes were introduced on the Great Plains by the Volga Germans who settled in North Dakota, Kansas, Montana and neighboring states.

The exports were small-scale until the 1860s, when bad crops in Europe, and lower costs due to cheaper railroads and ocean transport, opened the European markets to cheap American wheat.

World War I saw large numbers of young European farmers conscripted into the armies, so Allied countries, particularly France and Italy depended on American shipments,[122] which ranged from 100,000,000 to 260,000,000 bushels a year.

Cotton quickly exhausts the soil, so planters used their large profits to buy fresh land to the west, and purchase more slaves from the border states to operate their new plantations.