Agriculture in Mexico

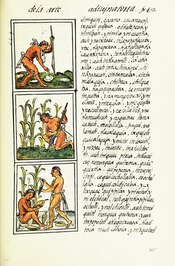

Mexico is one of the cradles of agriculture with the Mesoamericans developing domesticated plants such as maize, beans, tomatoes, squash, cotton, vanilla, avocados, cacao, and various spices.

[3] Agriculture was the basis of the major Mesoamerican civilizations such as the Olmecs, Mayas and Aztecs, with the principal crops being corn, beans, squash, chili peppers and tomatoes.

In the early conquest period, Spaniards relied on crops produced by indigenous in central Mexico and rendered as tribute, mainly maize, following existing arrangements.

[6]'[7] Studies found that haciendas were, in fact, not inefficiently organized and badly managed, nor did the concentration in land ownership result in waste and misallocation of resources.

In economic terms, benefited in ways that small holders and indigenous communities could not, since they had economies of scale, access to outside credit, information about new technologies and distant markets, a level of protection from predatory officials, and greater security of tenure.

[9] In Mexico City, chinampa agriculture was highly productive and labor intensive, supplying the capital, with land continuing to be held by indigenous farmers into the twentieth century.

[10] The Spanish introduced a number of new crops such as wheat, barley, sugar, fruits (such as pear, apple, fig, apricot, and bananas) and vegetables, but their main contributions were domesticated animals, unknown in Mesoamerica.

"[4][13] With the discovery and exploitation of large-scale silver deposits in Zacatecas and Guanajuato, cultivated areas outside of traditional agriculture expanded, particularly in the Bajío, which became the bread basket of Mexico producing the imported grain, wheat.

Unlike central Mexico, which had a long indigenous tradition of sedentary agriculture, much of the Bajío was a marshy wetland not continuously occupied or cultivated.

For the Spaniards, the Bajío was a disappointment, since there were no deposits of precious metals and no indigenous populations with existing hierarchies, but the region did show promise for initially the grazing of cattle and later agriculture.

With population growth in silver mining cities in the eighteenth century, agriculture expanded and cattle grazing was displaced to more marginal lands and declined in importance.

[14] A number of native plant and animal species from Mexico proved to have commercial value in Europe, leading to their mass cultivation and export including cochineal and indigo (for dyes), cacao, vanilla, henequen (for rope), cotton, and tobacco.

A high quality, fast red dye from small cochineal insects that were cultivated and collected from the nopal cactuses on which they thrived was an extremely important export to Europe, the second most valuable after silver.

[4][13] In the eighteenth century, when the Spanish crown was seeking new sources of income, it created a monopoly on tobacco production and processing, restricting cultivation to areas around Orizaba.

An advantage of church-owned haciendas over privately held ones was that unlike individual hacendados, whose deaths triggered a division of property among the heirs, the church as a corporation continued to consolidate its wealth over time.

Political turmoil continued until the last quarter of the nineteenth century with the coup by liberal army general Porfirio Díaz.

Once he had consolidated power, large haciendas were encouraged to develop commercial farming for export, made possible by the building of railroads to take products to market at low freight rates.

The result afterwards was the breakup of most large private landholdings to be redistributed, especially under a system of common tenancy regulated by the government called ejidos.

[2][23] By the end of the 1930s, haciendas almost entirely disappeared from central and southern Mexico with numerous small holdings of ten to twenty acres as well as ejidos becoming dominant.

[26] Research facilities developed new strains of wheat, maize, beans, and other crops, to engineer a variety of desirable traits, such as disease resistance, high protein content.

[27] Seeds and inputs of fertilizer and pesticides for irrigated agriculture were suited to Mexico's northwest, but required more capital than small-scale cultivators could afford.

In order to be competitive, Green Revolution crops had to be cultivated and harvested by machinery, which meant that it was economically viable only with large-scale farms.

[2] The Mexican government initiated programs in the 1970s and 80s to encourage family planning and the utilization of birth control, in order to reduce surging population growth.

Many farmers still survive on subsistence agriculture earning cash by selling excess crops in local markets, especially in central and southern Mexico.

A number of U.S. agribusiness enterprises have significant investments in Mexico, including Campbell Soup, General Mills, Ralston Purina and Pilgrim’s Pride.

[23] New grain initiatives of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador have reduced subsidies to middle and large producers with the objective of increasing smaller scale production for national consumption.

Ejidos were created in the first half of the 20th century to give Mexican peasants rights over redistributed lands, but this did not include leasing or selling.

However, most commonly held lands such as ejidos are characterized by small plots worked by families which are not efficient nor qualify for financial products such as loans.

[30] Main crops include corn, sugarcane, sorghum, wheat, tomatoes, bananas, chili peppers, oranges, lemons, limes, mangos, other tropical fruits, beans, barley, avocados, blue agave and coffee.

In the north open-range methods are giving way to rotational grazing systems, with some natural pastures enhanced by means of irrigation, top-seeding and fertilization.