Almoravid dynasty

[14] The Almoravids emerged from a coalition of the Lamtuna, Gudala, and Massufa, nomadic Berber tribes living in what is now Mauritania and the Western Sahara,[15][16] traversing the territory between the Draa, the Niger, and the Senegal rivers.

[15] The Almoravids expanded their control to al-Andalus (the Muslim territories in Iberia) and were crucial in temporarily halting the advance of the Christian kingdoms in this region, with the Battle of Sagrajas in 1086 among their signature victories.

[22] The Almoravid period also contributed significantly to the Islamization of the Sahara region and to the urbanization of the western Maghreb, while cultural developments were spurred by increased contact between Al-Andalus and Africa.

The last Almoravid ruler, Ishaq ibn Ali, was killed when the Almohads captured Marrakesh in 1147 and established themselves as the new dominant power in both North Africa and Al-Andalus.

The term is related to the notion of ribat رِباط, a North African frontier monastery-fortress, through the root r-b-t (ربط "rabat": to tie, to unite or رابط "raabat": to encamp).

[citation needed] Whichever explanation is true, it seems certain the appellation was chosen by the Almoravids for themselves, partly with the conscious goal of forestalling any tribal or ethnic identifications.

Around 1035, the Lamtuna chieftain Abu Abdallah Muhammad ibn Tifat (alias Tarsina), tried to reunite the Sanhaja desert tribes, but his reign lasted less than three years.

[51][52] Historian Amira Bennison suggests that some Almoravids, including the Guddala, were unwilling to be dragged into a conflict with the powerful Zanata tribes of the north and this created tension with those, like Ibn Yasin, who saw northern expansion as the next step in their fortunes.

[71] Shortly after founding the new city, Abu Bakr was compelled to return south to the Sahara in order to suppress a rebellion by the Guddala and their allies which threatened the desert trade routes, in either 1060[72] or 1071.

Another Almoravid commander, Mazdali ibn Tilankan, who was related to both men, defused the situation and convinced Ibrahim to join his father in the south rather than start a civil war.

Ceuta, controlled by Zenata forces under the command of Diya al-Dawla Yahya, was the last major city on the African side of the Strait of Gibraltar that still held out against him.

[93] The nascent Almoravid state was funded in part by the taxes allowed under Islamic law and by the gold that came from Ghana in the south, but in practice it remained dependent on the spoils of new conquests.

[104] However, criticism from Conrad and Fisher (1982) argued that the notion of any Almoravid military conquest at its core is merely perpetuated folklore, derived from a misinterpretation or naive reliance on Arabic sources.

[106] Dierke Lange agreed with the original military incursion theory but argues that this doesn't preclude Almoravid political agitation, claiming that the main factor of the demise of the Ghana Empire owed much to the latter.

[108] This interpretation of events has been disputed by later scholars like Sheryl L. Burkhalter,[109] who argued that, whatever the nature of the "conquest" in the south of the Sahara, the influence and success of the Almoravid movement in securing west African gold and circulating it widely necessitated a high degree of political control.

[110] The Arab geographer Ibn Shihab al-Zuhri wrote that the Almoravids ended Ibadi Islam in Tadmekka in 1084 and that Abu Bakr "arrived at the mountain of gold" in the deep south.

It was in this same year that Alfonso VI, king of Castile and León, led a military campaign into southern al-Andalus to punish al-Mu'tamid of Seville for failing to pay him tribute.

[130][131] However, the Almoravids did not send enough forces to oppose El Cid's return and Ibn Jahhaf undermined his popular support by proceeding to install himself as ruler, acting like yet another Taifa king.

[135] In 1097, the Almoravid governor of Xativa, Ali ibn al-Hajj,[131] led another incursion into Valencian territory but was quickly defeated and pursued to Almenara, which El Cid then captured after a three-month siege.

Like the previous Taifa rulers, he continued to pay parias to the Christian kingdoms to keep the peace, but popular sentiment within the city opposed this policy and increasingly supported the Almoravids.

[169] Also in 1155, the remaining Almoravids were forced to retreat to the Balearic Islands and later Ifriqiya under the leadership of the Banu Ghaniya, who were eventually influential in the downfall of their conquerors, the Almohads, in the eastern part of the Maghreb.

"[183] At first, the Almoravids, subscribing to the conservative Maliki school of Islamic jurisprudence, rejected what they perceived as decadence and a lack of piety among the Iberian Muslims of the Andalusi taifa kingdoms.

[191] The decorative theme of having a regular grid of roundels containing images of animals and figures, with more abstract motifs filling the spaces in between, has origins traced as far back as Persian Sasanian textiles.

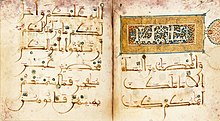

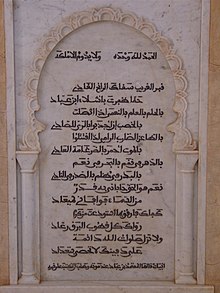

Its decoration is still in the earliest phases of artistic development, lacking the sophistication of later volumes, but many of the features that were standard in later manuscripts[199] are present: the script is written in the Maghrebi style in black ink, but the diacritics (vowels and other orthographic signs) are in red or blue, simple gold and black roundels mark the end of verses, and headings are written in gold Kufic inside a decorated frame and background.

[200] A similarly sophisticated Quran, dated to 1143 (at the end of Ali ibn Yusuf's reign) and produced in Córdoba, contains a frontispiece with an interlacing geometric motif forming a panel filled with gold and a knotted blue roundel at the middle.

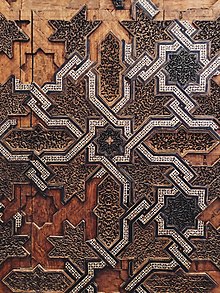

[205][206][207][208] Manuel Casamar Perez remarks that the Almoravids scaled back the Andalusi trend towards heavier and more elaborate decoration which had developed since the Caliphate of Córdoba and instead prioritized a greater balance between proportions and ornamentation.

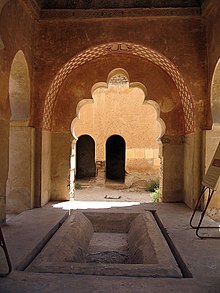

The Almoravids adopted the architectural developments of al-Andalus, such as the complex interlacing arches of the Great Mosque in Córdoba and of the Aljaferia palace in Zaragoza, while also introducing new ornamental techniques from the east such as muqarnas ("stalactite" or "honeycomb" carvings).

[216][217] Eventually, circa 1126, Ali Ibn Yusuf also constructed a full set of walls, made of rammed earth, around the city in response to the growing threat of the Almohads.

Built out of rubble stone or rammed earth, they illustrate similarities with older Hammadid fortifications, as well as an apparent need to build quickly during times of crisis.

During his reign, Ali Ibn Yusuf added a large palace and royal residence on the south side of the Ksar el-Hajjar (on the present site of the Kutubiyya Mosque).