Alternative law in Ireland prior to 1921

Alternative legal systems began to be used by Irish nationalist organizations during the 1760s as a means of opposing British rule in Ireland.

These alternative justice systems were connected to the agrarian protest movements which sponsored them and filled the gap left by the official authority, which never had the popular support or legitimacy which it needed to govern effectively.

[7] Trust in the judicial system was further eroded by the wrongful conviction and execution of Maolra Seoighe, a monolingual Irish speaker who could not understand the court proceedings, for the 1882 Maamtrasna murders.

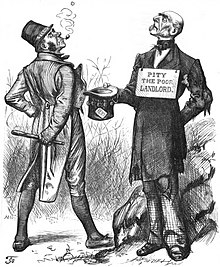

The feudal idea, which views all rights as emanating from a head landlord, came in with the conquest, was associated with foreign dominion, and has never to this day been recognized by the moral sentiments of the people ...

In the code's early version, practiced by the Whiteboys secret society beginning in the 1760s, it had a reactionary character which looked back to an era when there had supposedly been a reciprocal relationship between landlords and tenants.

[14] The idea of "unwritten law" was expressed and refined by the Young Ireland activist James Fintan Lalor (1807–1849), who insisted that the Irish people had allodial title to their own land.

[17] The tenets of the unwritten law appeared in "speeches, resolutions, placards, boycotts ... threatening letters and acts of outrage".

They began in northern Ireland to combat the Protestant Orange Order, but later expanded into agrarian agitation and spread southward.

[23] According to American historian Kevin Kenny, the alternative law as understood by the rural poor is the most convincing explanation for the violence practiced by these societies.

Rather than a civil war by the Irish against a supposedly alien landlord class, the violence was understood as retributive justice for violations of traditional landholding and land-use practices.

[25] Punishments ranged from digging up new pasture land in an effort to free it up for potato cultivation, tearing down fences on newly-enclosed areas, mutilating or killing livestock, to threats and attacks on landlords' agents and merchants judged to charge exorbitant prices.

Their popularity threatened British rule in Ireland;[31] O'Connell was arrested and charged with three counts of conspiracy in connection with the tribunals.

[32] The Repeal Association crumbled after the Great Famine (1845–1849), and the Ribbon Societies assumed its role as arbiters of land and wage disputes.

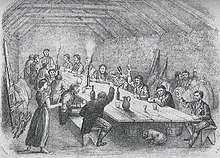

[39] American historian Donald Jordan emphasizes that despite their common-law trappings, the tribunals were essentially an extension of the local Land League branch and adjudicated violations of its own rules.

[49][50] In his 1892 book, Ireland under the Land League, Charles Dalton Clifford Lloyd described how the law's enforcement was difficult because many people refused to cooperate with the official justice system.

Refusal to rent transportation equipment to the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) paralyzed the police in Kilmallock, and people turned to the Land League rather than magistrates to resolve disputes.

[55]Conservative jurist James Fitzjames Stephen wrote that boycotts amounted to "usurpation of the functions of government", and should be considered "the modern representatives of the old conception of high treason".

[52][56] The government passed the Protection of Persons and Property Act 1881, which provided for the detention without trial of anyone suspected of treasonous activity or who tried to subvert the rule of law, to combat the underground state.

Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone had previously refused to suspend habeas corpus, saying that a Coercion Act would only be justified if Land League agitation threatened not only individuals but the state itself.

[58] The key provisions of the National League's code forbade paying rent without abatements, taking over land from which a tenant had been evicted, and purchasing their holding under the 1885 Ashbourne Act (except at a low price).

[59] Other forbidden activities included "participating in evictions, fraternizing with, or entering into, commerce with anyone who did; or working for, hiring, letting land from, or socializing with, [a] boycotted person".

People accused of violating the League's code would be summoned to a meeting with the plaintiff and the board of the local UIL chapter; evidence would be heard, a verdict reached and punishment imposed.

[74] The appearance of fairness and impartiality was essential to encourage parties to bring their grievances to UIL courts, and the branches strove to maintain that image.

[75] Although the "law of the League" was partially derived from the central leadership's guidance and its 1900 constitution, local branches also pressured national leaders to include their own issues.

[81] The courts were favoured by Sinn Féin because they adhered to the principle of self-reliance in all matters, and arbitration between two parties in a dispute was legal and binding when the participants agreed to abide by a verdict.

[87] Their operation was very similar to the British courts they replaced, and historian Mary Kotsonouris described them as "primarily concerned with the protection of property".

[90] The IRA attacked everyone connected with the British judicial system, and declared that "every person in the pay of England (magistrates and jurors, etc.)

[95] The RIC lost control of much of Ireland due to the Irish War of Independence, and rulings from British courts could not be enforced.

[85] Count Plunkett requested a petition of habeas corpus for the detention without trial of his son, George (an anti-Treaty guerilla), in 1922 after the split between Irish nationalists over the treaty.

[97] The Dáil court system was shut down and declared illegal after this incident, although a commission was appointed to iron out the loose ends in open cases.